This is the first post in a series analyzing the draft Bicycle Master Plan update, which is currently taking public comments. There is a meeting tonight (Tuesday) 5:30–7:30 at UW’s Gould Hall and a November 15 online lunchtime meeting.

Neighborhood greenways have huge potential in Seattle, and the idea has captured the hearts of neighborhood groups, politicians and transportation planners alike. But as the city starts upgrading its first miles of residential streets into greenways, it is clear that, understandably, the city still has a lot to figure out about how, where and why to build them.

This is not an insult to the city at all. Figuring out the answers to those questions can only be done through trial, error and the exact kind of public process the city is setting out to do. But judging by the sometimes odd placement of neighborhood greenway routes on the draft Bicycle Master Plan map and the tone of conversations I have been hearing, it would behoove us to try to come up with a few loose guidelines for talking about neighborhood greenways.

The biggest point I want to make is that a neighborhood greenway has vastly different—and in many ways superior—goals than simply being a bicycle route alternative to a busy commercial street. Any talk of “getting bikes off the car streets” or using neighborhood greenways as an argument against a bike lane or cycle track project is counterproductive and a bad thing for road safety in Seattle. To argue these points is to vastly understate the benefits and goals of both neighborhood greenways and bike lanes or cycle tracks.

Here are the goals of adding bike lanes to neighborhood arterial streets:

- Improve access to neighborhood businesses for all people, regardless of age, ability and how they got there.

- Improve safety for all users, whether they are on foot, bike or in a car. Streets redesigned to include a bike lane of some sort have been shown to dramatically reduce injuries from traffic collisions, including people in cars.

- Increase the number of safe crosswalks on busy streets, dramatically increasing the “walkshed” of a neighborhood and placing more residents within easy walking and biking distance of more neighborhood destinations, like parks, schools and businesses.

- Provide a safe bicycle route. Due to geographic and highway-imposed limitations, many busy streets in Seattle are the only realistic options for travel by any mode.

Here are the main goals for neighborhood greenways as I see them (Seattle Neighborhood Greenways has a similar list):

- Connect destinations within a neighborhood—such as parks, schools and businesses—using low-traffic, mostly-residential streets and trails that are comfortable and safe for people of all ages and abilities.

- Create new park-like spaces where people feel comfortable traveling and playing. This is accomplished by lowering traffic levels (really, only people living or visiting on those streets should be driving there) and by engaging the community to make the greenways unique and special places as they see fit. The city has also been planting extra trees and could increase the number of rain gardens and other greenery to make the streets even more park-like.

- Create new, efficient people-scaled transportation corridors. This means turning stop signs on residential cross-streets to make biking and walking travel faster, but it also means adding new ADA-compliant crossings at busy streets that feel comfortable for everybody. It is also a way to create fast, efficient and safe bike routes both for intra-neighborhood and inter-neighborhood travel alike. More on this point below.

Neighborhood greenways are so much more than an ‘alternative’

Sometimes, a neighborhood street located a block or two from a busy arterial street will be a good candidate for a neighborhood greenway, especially in relatively flat neighborhoods like Ballard. But some of my favorite neighborhood greenway proposals actually create brand new corridors that change the way I look at and travel through the city.

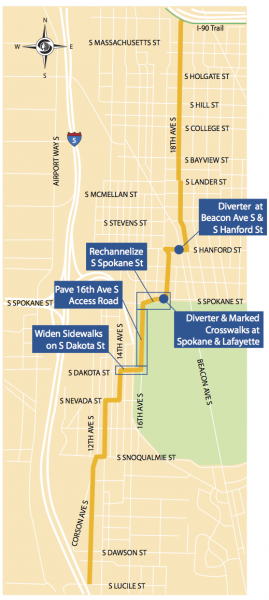

A great example of this is the Beacon Hill neighborhood greenway from the I-90 Trail to Georgetown. There is no comparable route for people driving. Instead, it reinvents a residential street network destroyed by I-90 and I-5 to create a new people-scaled corridor across the neighborhood that connects homes with light rail, commercial centers, schools and the library in a way no existing busy street can. In the process, it also creates a new transportation option for people who live, work of play in Georgetown, an often-neglected neighborhood.

Thinking big with cycle tracks

However, even with all the promise of neighborhood greenways, safe and comfortable bike access on major streets is an absolutely essential part of a biking- and walking-friendly future in Seattle. For all the praise Portland gets for its impressive and ever-growing neighborhood greenway network, access on key commercial streets is often ignored. It is clear that Portland will need to address access and safety issues on its commercial drags if it wants to join the ranks of global bike-friendly cities (rather than just sit comfortably at the top among large US cycling cities, an unfortunately low bar).

Seattle is more dense and has more geographic constraints than Portland. We must make bold decisions about bicycle access on major commercial streets, drawing as much from New York City and Washington D.C. as we draw from Portland. And, in many ways, Seattle will need to write the book on US bike facilities as we deal with sometimes unavoidable steep grades and the tricky issue of simultaneously growing bike and transit networks.

If Seattle is going to be “the city of the future,” then safe and comfortable bike facilities on streets like Rainier Ave, Beacon Ave, Lake City Way, Airport Way, Market St and Eastlake Ave are inevitable. I am encouraged that the draft Bicycle Master Plan map includes these streets and many more as candidates for protected cycle tracks, and you should be, too.

At the BMP public meeting at City Hall last week, I listened to people who seemed taken aback by the idea of a cycle track on these major streets. In some ways, I think they were afraid of the political battles some of the projects might face. But in a lot of ways, the plans challenged people who are so used to avoiding these key streets they don’t realize how accustomed they had grown to the idea of the roads being off-limits (or, at least, destined to be uncomfortable).

There is no such thing as a car street. Streets are for people, and Seattle should support a plan that gives a bold 20-year vision that includes family-friendly changes to the streets that front our city’s biggest destinations.

The day we take our first ride down a Rainier Avenue cycle track is closer than you think.

Comments

4 responses to “Bike Master Plan: Neighborhood greenways are much more than ‘alternatives’ to bike lanes”

The cycletrack on 45th/46th/Market is I think the most striking element of the plan. There’s a lot of bridge work in there, but that’s a a mere matter of money. That is a long and important corridor with a lot of challenges, that will face a lot of resistance.

An SDOT representative talked about convincing business owners, particularly along 45th in Wallingford, that they have more to gain from cycletracks and transit access than parking and car access. True or not, a car-light 45th with no street parking is a really radical vision (particularly considering 45th’s position as a route to I-5 and Aurora). And I hope that our real, current needs of getting across I-5 and Aurora in this corridor aren’t kept on hold until that vision is more widely accepted, since it may never happen. It seems to me much of the private off-street parking is generally underutilized and could be converted to parking shared among businesses (with money going to current owners) to mitigate total loss of street parking. I’m not sure how far that sort of thing would go. Even if nothing like that goes at all, neighborhood greenway groups are putting together alternate routes today, we just can’t get across I-5 and Aurora so easily.

Judging by how SDOT’s greenways have looked so far, I think they may have mostly ignored the point of why those greenways were pushed to begin with.

I have to admit I’m still a little confused at the distinction you’re drawing between greenways and cycle tracks. Considering your praise for how the Beacon Hill greenway improves connectivity between neighborhoods (not just serving destinations within Beacon Hill), which is better for long-distance commutes, or does that depend? And which would you prefer, a greenway on 46th/47th crossing I-5, the existing 43rd/44th greenway, a cycle track on 45th, or some combination?

Ok, let’s use Wallingford as an example. Ignoring issues with installing a cycle track on 45th, for the sake of argument we will say that it has been done. If you were traveling from the U-District to Fremont or were traveling to a destination on 45th, the cycle track would very likely be the route you would use.

If you live in Wallingford and are headed to school or the park, you would use the greenway. If you are a kid looking for a safe street to cruise around the neighborhood, you would use the greenway. If you are looking for a route that is further from car exhaust and is quieter, you might go out of your way to use the greenway no matter what.

If you were headed to the 41st Street Bridge from the U-District, you would probably use the greenway, since 45th doesn’t go there (thus, it’s a “new corridor”).

Both projects have value to the neighborhood, and neither supersedes the other. 45th St, while it is better than four-lane commercial streets, is still stressful to cross on foot or bike (or car, for that matter). So a cycle track, which would also make streets easier and safer to cross, would also make it easier to access the 44th St greenway from north of 45th. In The same way, the enhanced crossing at 43rd and Stone Way would make it easier to access a cycle track on Stone (if one existed).

Both are complimentary visions of a safer neighborhood that values walking and biking. Does that answer your question?

[…] an “alternative” route for bikes (side streets that could be neighborhood greenways). As we have written before, this is a huge mistake and a misuse of the neighborhood greenway idea. This is our chance to do […]