A road diet, rechannelization, safe streets redesign, complete streets project or whatever you want to call it: It works.

Troy Heerwagen has created an excellent interactive infographic over at his Walking in Seattle blog that shows how consistently effective Seattle’s long history with low-cost safe streets redesigns has been. Many of our city streets were overbuilt during a 20th Century era of road engineering that put the high speed movement of cars above safety for people. Often, this manifested in the form of streets with too many lanes and/or lanes that are too wide, both of which lead to speeding and increased likelihood for injury and death. Four lane roads might work on a rural highway, but they don’t work in urban neighborhoods.

As Seattle works towards Vision Zero, we are going to need hundreds more miles of these redesigns. So it’s great that the city already has so much experience to build on.

Seattle was among the first cities in the nation to figure out that the same number of vehicles could travel on a much safer, less stressful three-lane street (one lane in each direction with a center turn lane) and has been redesigning streets in this style since the 70s. As time goes on, their designs have improved and most often now include better crosswalks and bike lanes, creating a more complete street.

These redesigns can vary widely in cost depending on how far the changes go. Simply repainting a street to have a safer design can cost in the neighborhood of $50,000 – $100,000 per mile (including community outreach). That might sound like a lot of cash, but in transportation infrastructure terms it’s pennies.

Repaving, improving sidewalk curbs, installing crosswalk islands or raised crosswalks, building protected bike lanes and transit islands, etc. all add to the cost and benefits of the projects. For example, though the safety data is strong for many of Seattle’s past road diet projects that included bike lanes, those bike lanes were often only paint and located uncomfortably close to busy traffic and opening car doors. Protected bike lanes cost a bit more, but the extra separation from general traffic appeals to many more people.

City estimates for street redesign projects with protected bike lanes range widely in cost from $350,000 to $5 million per mile based on experiences in other cities and the planned Roosevelt Way bike lane. Costs increase in denser areas with more traffic signals and repaving needs or if the city opts for better crosswalks or more attractive barrier options, like permanent planter boxes instead of plastic reflective posts.

When choosing projects for safety upgrades, Seattle is prioritizing dangerous streets based in large part on collision and injury data. Unfortunately, we have a lot of that data. The following streets were prioritized for quick action in the Vision Zero plan released last week:

- Rainier Ave S (new meetings just announced)

- Lake City Way

- SW Roxbury Street

- 35th Ave SW

- Banner Way

The city has also highlighted the following streets to “plan and develop long-term multimodal improvements.”

- Delridge Way SW

- East Marginal Way

- Yesler Way

- Greenwood Ave N

- 3rd Ave

- Beacon Ave S

The city will also start work this year on improving safety on 23rd Ave in the Central District and Roosevelt Way as part of larger repaving projects there. North Broadway on Capitol Hill is in the design phase as part of a planned streetcar extension and will continue the complete street design currently south of Denny Way.

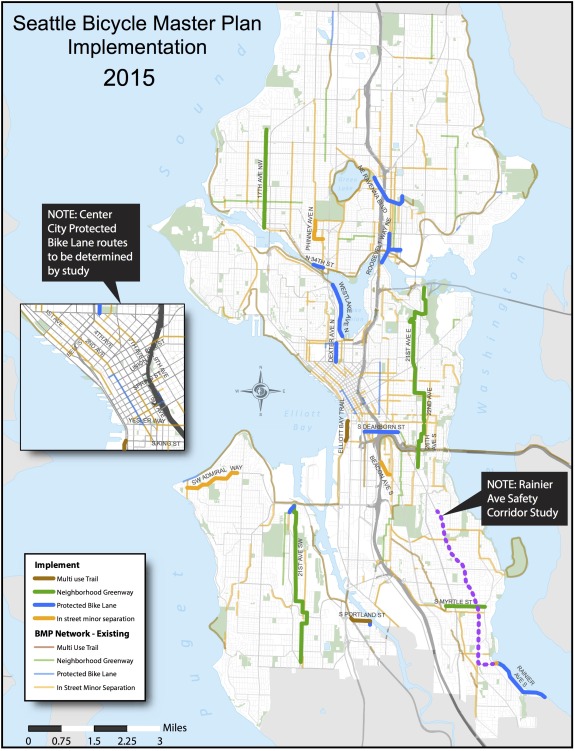

And, of course, the city plans to build more than seven miles of protected bike lanes and 12 miles of neighborhood greenways in 2015, as outlined in the Bike Plan Plan:

But Seattle’s supply of dangerous, overbuilt streets remains plentiful. The city is headed in the right direction, but we need to significantly boost investment if we’re gonna get on track to eliminate traffic deaths and seriously injuries by 2030.

But Seattle’s supply of dangerous, overbuilt streets remains plentiful. The city is headed in the right direction, but we need to significantly boost investment if we’re gonna get on track to eliminate traffic deaths and seriously injuries by 2030.

Comments

23 responses to “Infographic: Seattle’s low-cost safe streets projects work really well”

“Many of our city streets were overbuilt during a 20th Century era of road engineering that put the high speed movement of cars above safety for people. ”

Why were roads designed like this in the first place? Was life less valuable in 1950’s America than it is today?

That’s a big question. Some of it is just not really realizing the cost of these engineering standards. Some is just motor brain, running road designs through car-throughput tests without care for any other road users. Some is that there was so much political pressure to ease traffic congestion, and more lanes was (wrongly) seen as the way to accomplish that.

This is the same era we were building suburban communities without sidewalks on purpose (!). Ask Lake City or Rainier Beach residents how that turned out. We were also building amazing floating bridges across Lake Washington without any space for walking or biking. We had some strange ideas about urban space back then.

Basically, this: http://youtu.be/TwA7c_rNbJE

We need that atomic tunneling machine!… Oooo. I want to dig bicycle tunnels right through capital hill from downtown to leschi!

Remember, the 1950’s were sixty years ago. A lot has changed, population, traffic, land use just to name a few. What might have worked fine for thirty or forty years may no longer meet the needs of a changing city and region.

While we know what is needed now, we would have to be pretty full of ourselves to imagine what would work now will meet the needs of our children’s children another sixty years into the future.

Well, they do and they don’t.

Many of these band aid fixes (e.g. 2nd Ave) are sold to the community as a great accomplishments, but I believe this city can and should do better. Those cheap fixes last only as long as the paint lasts on the road. Road conditions in Seattle are poor and anyone riding on these new “bike facilities” knows what I am talking about. In some cases cyclists have to pay more attention to what they encounter on the bike paths (pot holes, pavement cracks or offsets) than on traffic. It is disappointing to see that SDOT keeps improvising with paint on roads rather than providing well executed bike facilities. In light of the wonderful post about Ballard Bridge (yesterday) it is also frustrating to see that Ballard bridge and the bike facilities leading up to it are not on the list mentioned above.

I do agree with the closing statement above: “But Seattle’s supply of dangerous, overbuilt streets remains plentiful. The city is headed in the right direction, but we need to significantly boost investment if we’re gonna get on track to eliminate traffic deaths and seriously injuries by 2030.”

The streets still need a lot of real fixes even though the “road diet” is good. I think Seattle is the city where you most need a mountain bike on normal streets. I usually only use a road bike outside of Seattle where the potholes, cracks, bumps and glass seem to decrease greatly.

You are very right on the mountain bike.

Living in Seattle is the reason why I use a cyclocross bike to commute, and why my motorcycle is a dual-sport.

I’ll speak about Nickerson, as I’ve cycled it many, many times. The street definitely seems safer to me. What makes the biggest difference is the center turn lane. The bike lanes (which partially exist) are of lesser importance for the usual reasons – parked cars, poor visibility. However, the center turn lane makes it easy for vehicles to pass without pushing me into the curb. More streets with center turn lanes: yes!

Now, there are some problems on Nickerson. There are some choke points. One in particular is near the high voltage electrical tower. There’s a center island for peds and the tower causes a bulge into the roadway. As a cyclist, I need to merge with the traffic to get through. This is very uncomfortable.

I appreciate the need to make ped crossings easier, but we’re doing so at the expense of safe cycling. How can we address this?

I’m a fan of the Dutch style: pedestrian islands on the outside of the bike lane.

http://wiki.coe.neu.edu/groups/nl2011transpo/wiki/14b2b/images/fcf34.JPG

Additional protection against right-hook collisions for cyclists, and pedestrians have an even short crossing distance.

Stone Way’s road diet did not eliminate crossing danger, in my view. The road is just as wide as it ever was, and drivers are more distracted than ever. The designated crosswalk at N. 41st had two bad injury accidents in the past 15 months. SDOT has moved to improve markings, but the road is still as wide as ever. I think there is the same danger wherever at wide intersections, where the driver who is turning in a wide arc and has a lot to watch for (on top of being distracted). I think the wide streets must be narrowed with other engineering approaches, such as median planting strips and pylons, whatever gets the drivers to slow down and really pay attention to what is in their (smaller) field of view.

I agree. Stone Way design did not go far enough. It was an improvement, but still dangerous.

I tried googling, but I couldn’t find before-and-after lane widths for Stone Way. Anyone know how wide are the lanes now?

Then there’s 20th Ave NW in Ballard, which was modified about 4 years ago. Not so much a road diet as a road starvation. In a 10 block (very short north-south Ballard blocks) stretch, they took a two lane road, with center lane and parking each side (which was just fine for cycling in my opinion) and replaced it with two drive lanes, two bike lanes and parking each side. The bike lanes are nice, but without the center lane, I believe it became more dangerous. Cars don’t slow down at all, but rather shift right, towards the bike lane.

Add that to the fact that on either end, the lanes just end and there’s no bike facilities to connect to and you have a head scratcher. I’d rather have the center lane than a bike lane for a street like 20th.

I agree, the 20th Ave. NW bike lanes weren’t needed. At the time it was redone, I commented on this blog that it was just a waste. At the time SDOT was really patting themselves on the back for how many miles of sharrows and door zone bike lanes it was making, and this stretch wasn’t controversial and was easy to do.

Why is Troy using the term “road diet”? SDOT stopped using it in 2010. Rechannelization has been proven to be more effective. Using the old term unwinds a lot of progress we have made in the past five years.

SDOT isn’t really using the word “rechannelization” much either these days. Here’s the NE 75th “Road Safety Corridor Project”: http://www.seattle.gov/transportation/ne75th.htm

Here’s the Green Lake Way N “Safety Improvements” project: http://www.seattle.gov/transportation/greenlakeway.htm

Googling for “road diet” returns 160 million hits, nation-wide. Google for “road rechannelization” – 18,000 results, mostly from seattle (and people linking to SDOT PDFs). The wikipedia page for Rechannelization redirects to Road Diet. Rechannelization means nothing to the average person, who doesn’t think of roadway lanes as ‘channels’. The wikipedia page also calls it “lane reduction”, which makes more sense to the average person, even if it might sound negative. Rechannelization is engineer-speak that we probably shouldn’t be encouraging.

SDOT has certainly realized that calling something a road diet to people unfamiliar with the concept is a bad idea, but the rest of the nation is celebrating road diets and calling it by that.

The transition from “global warming” to “climate change” was successful because it was an accurate description, and it made sense to the average person. If we want to get the rest of the nation to use a word other than “road diet”, we need to provide a better alternative; “rechannelization” is not it. SDOT should probably lead the way on a new name, and them falling back to words like “safety project” seems like a pretty good sign that they’ve been unable to come up with a good, descriptive name for road diet projects.

On a very slow Friday afternoon, I played around with a few new Road Diet/Rechannelization names:

1. Road Streamlining (Sounds faster! People who drive cars would love that!)

2. Road Integration

3. Road Harmonization

4. Road Unification

5. Road Reorganization

6. Road Consolidation

7. Road Modernization

8. Road Concentration

9. Road Blend

10. Road Meshing

11. Road Remix

12. Road Mashup

Lane Balancing

No,

Lane Rebalancing

– when things get out of balance, you need to rebalance them!

[…] plenty of capacity for the traffic volume that Jackson Avenue carries; SDOT has done numerous other street rechannelizations that have shown this to be the case. Jackson Avenue also has discontinuous bicycle facilities […]

The research and case studies on 4 to 3 lane road diets overwhelmingly show their safety benefits. It’s amazing more cities aren’t retrofitting their 4 lanes, especially considering many road diets can be done at low cost with striping and no curb work.