The lucky among you do not remember the vicious fight over a 2011 road diet on NE 125th Street, which pitted neighbors against neighbors in a drawn-out and ugly battle over ten feet of road space in North Seattle.

The lucky among you do not remember the vicious fight over a 2011 road diet on NE 125th Street, which pitted neighbors against neighbors in a drawn-out and ugly battle over ten feet of road space in North Seattle.

Prompted by rampant speeding and a pattern of dangerous collisions, the city proposed changes that would keep traffic flowing, but in a way that was safer for everyone. The project changed a highway-style four-lane street from Lake City to Pinehurst to one with a general lane in each direction, bike lanes on both sides and a center turn lane.

A follow-up study recently released shows that the changes worked exactly as the city had predicted. NE 125th Street is now far easier and safer for people on bikes and people trying to cross the street on foot. The number of people biking on the street increased 114 percent, and the number of people walking increased 104 percent (2005-2012). On top of that, the number of car crashes and injuries declined significantly, and the street’s ability to handle the number of people trying to use it every day was maintained.

The fight that preceded the changes, however, was emotionally draining and depressing. But it may also have been a defining dark moment for bike advocacy in Seattle that created a wide-open space for a more family and neighborhood-oriented focus to earn the spotlight and finally reframe the discussion about safe streets.

The Battle

The city proposed a road diet on NE 125th Street in 2010, and all hell broke loose. A group of neighbors got angry and started posting road signs and letters opposing the project, and some even gathered signatures on a petition against the project. They expressed fears that the changes would cause traffic congestion and would increase traffic on side streets.

The Seattle Department of Transportation’s weapon of choice was data. They released piles and piles of percentages, vehicle speeds, daily traffic volumes and national traffic safety data. But no amount of data from SDOT explaining why Traffic Armageddon would not happen seemed to ease the concerns. In fact, it almost seemed to make people more angry.

How angry? Well, the Seattle Weekly ended up publishing a piece comparing me to a Klansman. Really, that happened.

I was in my first year of writing this blog, and I tried my best to anticipate the same faulty arguments that came up during difficult fights over Stone Way and Nickerson changes, confronting them as they popped up. It was like playing fact-check Whac-A-Mole.

Of course, most people don’t really respond well to being told they are wrong. Worse, the entire debate occurred under the framing of whether there was or was not a “War on Cars.” Even with the facts on your side, that’s a terrible place for the public debate to be held. Sitting in traffic is an awful experience, and here we were saying, “We just want to take a little bit of the road but, don’t worry, your traffic at least won’t get worse, we’re pretty sure.”

In retrospect, of course that didn’t work very well. The mayor may have decided to OK the project, but a lot of people had soured on the whole idea of bike lanes.

The changes became a symbol of how Mike McGinn only cared about people who bike. It no longer mattered that the primary impetus for the changes was general road safety, especially for people on foot. Every fact SDOT laid out was immediately disregarded as lies, pawns of a car-hating mayor trying to justify his land grab.

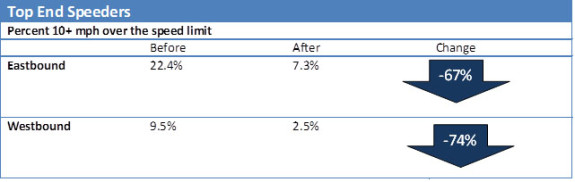

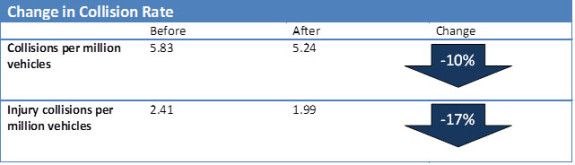

A follow-up study has shown that SDOT was exactly correct in their analysis of how the changes would affect traffic levels and traffic safety. Most importantly, high-end speeding decreased by as much as 75 percent, and injuries dropped 17 percent:

Not only is the road safer, but the number of vehicles moving down NE 125th actually increased slightly after the changes. The capacity of the street was not reduced, and it was plenty capable of absorbing an uptick in traffic as people began avoiding tolling on 520 by using 522 instead. NE 125th connects 522 to I-5.

Not only is the road safer, but the number of vehicles moving down NE 125th actually increased slightly after the changes. The capacity of the street was not reduced, and it was plenty capable of absorbing an uptick in traffic as people began avoiding tolling on 520 by using 522 instead. NE 125th connects 522 to I-5.

Remembering the awful fight — which dragged my personal reputation through the mud — I saw the SDOT study and immediately got excited to finally have my chance to rub it in the naysayers’ faces. But in writing this piece, I’ve discovered that the battlefield in the War on Cars is no longer active, and there’s nobody left to say, “I told you so.” It’s already overgrown, the weapons are abandoned and rusty. Flipping through old posts about NE 125th feels more like digging through an archaeological site.

It all seems so silly now. Like so many actual wars, we are left wondering, “What on Earth were we fighting about?”

Seattle Neighborhood Greenways

Just ten days after Mayor Mike McGinn wrote a lengthy letter explaining why he was going forward with the controversial NE 125th Street changes, I wrote the first post in a four-part series about two groups of neighbors — one in Wallingford and one on Beacon Hill — who had started getting together with the intention of gathering a coalition of residents, organizations and businesses in their neighborhoods to urge road safety changes. They were frustrated that they could not safely or easily bike to school or to the grocery store with their kids because the streets were too dangerous. This was my first big story about Seattle Neighborhood Greenways.

Here’s the first paragraph of that May 2, 2011 story:

Bicycle advocates have worked tirelessly to create safer routes across the city, between neighborhoods and towards downtown. Because of these efforts, each year commuting to work and otherwise traveling through out the city has become safer and more popular. But what about trips to the neighborhood park, to the bar or to the grocery store? What about the 40 percent of trips in America that are two miles or less?

With that, these neighborhood greenways groups completely reframed the discussion about safe streets. It was no longer about jockeying for precious road space during rush hour, it’s about everything we do as people who live in a city. It’s about the youngest and oldest of our neighbors. Dangerous streets divide our neighborhoods when we should all be connected. Dangerous streets hurt those we care about.

Most importantly, it doesn’t have to be this way. We now have a framework for organizing with our neighbors to make our neighborhood streets safe.

A couple months after the mayor’s decision, a series of people died while biking. Each death was a tragedy, but so many people died in such a short time frame that people were devastated and overwhelmed by the carnage.

Adonia Lugo (now the Diversity Manager at the League of American Bicyclists), Davey Oil (now co-owner of G&O Family Cyclery in Greenwood) and I organized the Safe Streets Social, a community bike ride that visited the memorial sites of Mike Wang, Brian Fairbrother and Robert Townsend. The ride was about showing support for those who had lost loved ones, but it was also about creating a safe space to talk about the trauma of road violence and about the need for both infrastructure and cultural changes if we are ever going to live in a truly safe city for cycling.

Mayor McGinn also took action, organizing the Road Safety Summit, which turned into the Road Safety Action Plan. Seattle Neighborhood Greenways leaders were invited to be part of the shaping of this plan, which puts people and neighborhoods at the forefront of the city’s road safety efforts.

The War on Cars was not won. Rather, we all just realized it never really existed in the first place.

Today, there are neighborhood greenway groups in more than 20 neighborhoods stretching beyond the Seattle borders. Neighbors are organizing in Central, South, West, and North Seattle. There are groups in Kirkland and Federal Way, with more popping up all the time.

And yes, there is a very active group in Lake City, where the battle of NE 125th Street was fought just a few years ago. Just last week, they took to one of the city’s most dangerous intersections holding picket signs urging people to pay attention to people in the crosswalks.

They are also helping to build a park that will be a key piece to the Olympic Hills neighborhood greenway. Here, neighbors are coming together because they want to create a park and a safe place for people of all ages to walk, bike and otherwise enjoy the place where they live together.

The fight over NE 125th Street was a huge learning experience for a bike advocacy movement that was growing out of its bike commuting and recreational riding shoes. It was becoming one key part of a safe streets movement that every single person is invited to join. Biking and safe streets was becoming mainstream, and it was time to change how we talk about city cycling or make way for people who will.

A simple and inexpensive road safety project on NE 125th Street turned into a bloody modal war pitting people who drive against people who bike in a fight for a couple feet of road space. It highlighted and exaggerated small differences between neighbors — what kind of vehicle you most often use — instead of building on points where we agree. Everybody wants streets to be safer. Everybody wants people of all ages to be able to get to the store, school or park safely and easily.

Everybody wants to live in a strong neighborhood in a strong city with healthy and efficient choices for getting around town. And that’s what safe streets are actually all about.

Comments

29 responses to “An archaeological dig on NE 125th Street, one of the final battles in the War on Cars”

Tom, thanks for all that perspective. And I am sorry for the abuse you took over 125th. Even before the data were released, the tired, bitter griping about 125th at EVERY gathering in Lake City where city staff were present was dissipating. The world had not come to an end. And there was anecdotal information from residents along and near the street. There will still be people who carp about how they never see a bike in the bike lane, but if they think it’s not worth some extra paint to make the whole road less lethal for everybody, they just have a bike-spleen problem (and a blind spot to the big picture) that none of us can help with.

Thank you for highlighting the LC Greenways efforts. Greenways are transforming the conversation in Lake City, where pedestrian safety, the great equalizer, is a critical issue and where people are hungry for positive action that can make their kids safer and their neighborhood a real community.

Thanks for all the work you’re doing! And no worries about the abuse I took. You shoulda seen the other guy!

I’m surprised to see you write, “But in writing this piece, I’ve discovered that the battlefield in the War on Cars is no longer active, and there’s nobody left to say, “I told you so.””, given the similar reactions to the proposed 23rd street road diet! (see comments on CD news: http://www.centraldistrictnews.com/2013/11/what-exactly-will-the-23rd-ave-greenway-be-its-up-to-you/)

I’m in no way claiming that road diets are no longer controversial!

The 23rd project is a mess, and outreach has been confusing and disjointed (I know because I live in the area). That doesn’t have anything to do with bikes, though.

I think some of the reactions on 23rd really do have to do with bikes, or the perception that all McGinn-era road diets were really about bikes. Early-on, before neighborhood greenways caught hold, proposals for 23rd included a cycletrack crammed hazardously into a busy street grid. Saner heads prevailed on that point, but it let the “anti McSchwinn” camp paint the entire corridor as yet another “war on cars” proposal.

Tom, thanks for pushing so hard in the early days. It’s paying off.

I’ve seen similar reaction and results for Nickerson st. Where would I go to see actual statistics for that route? In my observations, about the same amount of traffic gets through the corridor in the same amount of time. However the backups are longer since there is only one lane vs two to queue the waiting vehicles. Since almost all the intersections are unsignaled, that makes it a bit harder to cross (there are fewer gaps in traffic) but not too bad. It definitely feels safer to ride on. Way safer.

Yes, Nickerson saw very similar results. Data: http://www.seattlebikeblog.com/2012/03/01/collisions-drop-23-percent-on-redesigned-nickerson/

Also Stone Way: http://www.seattle.gov/transportation/docs/StoneWaybeforeafterFINAL.pdf

In fact, it has worked every time the city has done it. They have completed dozens since they started in the ’70s.

But… but this goes against my firmly-held gut-belief that McGinn is responsible for all road diets, and they always lead to chaos! ;)

Thanks for the well-written article, Tom, I think it offers some great perspective on how far we’ve come in just the last couple years. My greatest hope is that greenways and rechannelizations will become so normal and standard-course that the advocacy community will be able to shift their energy to bigger challenges.

“Of course, most people don’t really respond well to being told they are wrong.”

And this is so hard to overcome. When you present someone with the data to show that their fears are misguided and they still insist you are wrong what else can you do? The people who come out against these things seem to collectively stick their head in the sand.

It’s vital to have a powerful vision for how things could be better, and a united group of neighbors who are engaged and leading the effort. There will always be people who oppose a project, no matter what it is. And sometimes the people with fears are also well-organized. But so long as there is a solid, desirable vision, you can stay focused on that.

Re: “War on cars”

Why just this morning I rode up the elevator (after having changed out of my bikie clothes) with a delivery guy who was gloating that Mayor McGinn would soon be out of office. His hope was that on street parking would come back… I had to inform him that Mr. Murray was not going to put in more parking that his views on the street were very similiar.

Now gloating aside, I can see that from a delivery guy’s perspective, “I need 10 minutes of parking, to run inside a building” could be solved in a number of ways. One is to give him those 15 minutes free in the parking garage. Almost no one else would be able to drive in, park ride the elevators and be back out in that amount of time. All that would be needed is for the building management to recongnize the need. As a bicyclist, and occasional car driver, I want these guys off the street. Their parking in the loading zone makes my life more difficult and dangerous as I need that space so that I don’t get run down.

I wonder what it would take to make this possible besides a city code change.

I really like your idea. However, I think most loading zones are in front of businesses that don’t have any off street parking, let alone a garage. Downtown and the urban centers are where it would work, though. Even that is enough to merit attention to your idea. For the rest, they currently are allowed to park in the center turn lane (if there is one), which isn’t too bad.

I certainly have to agree with you that loading zones (with a truck in them) pretty much obliterate a bike lane.

Wait, is parking in the center turn lane actually legal for making deliveries? I always assumed it was illegal, but accepted.

Maybe I’m mistaken. I just spent some time looking through the SMC but didn’t find a specific mention. Over the years, two sources have told me it is encouraged by the city, though that doesn’t imply it’s legal. As Josh points out, the code seems to infer that it is generally legal.

Relating to wide vehicles, here’s another code often overlooked. It bans vehicles 80″ and wider from parking on *any* street except in industrial zones. I think “load and unload” is not counted as “parking”. But it’s something that could be enforced more to prevent unreasonable blockage of bike lanes. For example, often I find the private transit busses parked half into the bike lane while they are waiting to start their next circuit. When this happens during rush hour, it’s difficult to merge into traffic to go around the parked bus.

http://clerk.ci.seattle.wa.us/~scripts/nph-brs.exe?d=CODE&s1=11.72.070.snum.&Sect5=CODE1&Sect6=HITOFF&l=20&p=1&u=/~public/code1.htm&r=1&f=G

Parking on city streets is much less regulated than you’d expect. The underlying philosophy hasn’t changed in generations — the street is there to serve the people who live on it, they sometimes need to stop in odd places for a time, through traffic can put up with occasional inconvenience.

Seattle doesn’t outright ban parking in a traffic lane or center turn lane, it says you can’t do it if it *unreasonably* obstructs traffic:

“No person shall park a vehicle upon or along any street and exit such vehicle when traffic will be unreasonably obstructed thereby, or when, in areas designated for angle parking, the vehicle is of such a length as to obstruct the sidewalk or the adjacent moving traffic lane. Violation of this section constitutes a parking violation rather than a moving traffic violation.”

Where there’s more than one lane going your direction, it might be reasonable for one of them to be used for local deliveries. When there’s a center turn lane and a stopped vehicle isn’t blocking a turn, who is being unreasonably obstructed?

Yeah, I don’t know. I don’t have a problem with the city turning stretches of parking into delivery zones or 10-min zones, but I don’t know all the concerns related to the issue.

I like the idea that our transportation system is for the movement of people and goods. Deliveries are a part of that. Luckily, because it’s not a bike issue it’s not an issue I am super familiar with.

However, I wonder how many in-city deliveries could be done by cargo bike (further enabled by ever-improving electric-assist technology). I expect bike freight to be a growing industry over the next ten years. In fact, I bet there’s room right now for a bike freight company to start up in Seattle, if any of you were looking to start a business…

There is still a misguided design team out there making segragted and terrible bike paths that are adjacent to roads. The one that recently comes to mind is the Bellevue city engineers who put in a “raised, sort of sidewalk” path next to the West Lake Samamish Rd.

It’s failures are that there are many driveways which intersect across it, all the intersections with the adjacent roads to the West are not marked in anyway to alert a car that there will be bicyclists moving fast along them. And the edge is a raised curb, which made the regular traffic lanes unrideable, as there is no way to exit the roadway onto the bike path. It was obviously designed to get bicyclists out of the way of cars, not to make it safer to ride a bicycle as it’s clearly worse. This is the same bad design that they used up on 108th last spring. It’s clear that Bellevue doesn’t want bicyclists using the same road that cars use. Reflects the “Kemper Freeman” school of design… of out’a ma way, I’m driving to the store/school etc.

I think that what the bike hating group doesn’t realize that a lot of these traffic calming project benefit people who walk, jog and who are otherwise using two feet to get around. So, none of these should be a cars against bikes. For sure I am sure some of these people have kids and want them to play outside and not have a car mow into them while playing. Cars have even crashed into some of the bus stops on Rainier Ave and that has nothing to do with bicyclist.

Tom, this is a great article and I truly appreciate your support in raising awareness about the need for this kind of road change. I live near 125th and the change in the lanes have been a great for the neighborhood. It’s good to see that the data backs up why the road diet is needed. I will say, it got a bit nasty around here when the road diet was proposed. There will always be a segment that fears change, no matter what it looks like. Before the changes were made to 125th, it felt very unsafe to walk on the sidewalk considering there were people speeding along not a foot or so from the sidewalk. Yikes! With bike lanes and recent repaving, biking on 125th is immensely better. Keep up the good work!

Tom,

I remember well when they announced the road diet on 125th – I live in Pinehurst just south of 125th off of 20th. It was around the night out in the summer where i pedaled by and talked with some of my neighbors who were out having dinner. after years of trying to cross 125th to get to the 41 bus or take a left to go up the hill to 15th and almost getting hit trying to cross 4 lanes of fast traffic I was ecstatic about the change coming to our ‘hood. at two of these night out groups people were handing out the literature that was so wrong. and because I was on a bike they immediately got in my face about how bad these changes were. THEY WERE SO WRONG! if you are driving or pedaling you can now turn left safely and there is even a cross walk now at 20th and 125th after the repave. The bike lanes are an added benefit – it is the reduction in speed and ability to cross the road that makes all the difference. Just before they did the road diet I was walking to bus and a SPD vehicle stopped for me in the right hand land. I started to cross 125th and the car in the LH lane almost took me out going 40 mph down the hill not bothering to stop for a pedestrian. the officer just put her hands up and I could read her lips – Sorry.

thanks for the abuse you took – i took a lot too back then. ditto on keeping up the good work here!

Hey Tom et al.,

I’m a recently returned Seattleite (10 years away) who has been very frustrated with traffic on “lane diet” and slow speed-limit roads. Broadway has become undrivable, I hear 23rd is next and the four-lane main thoroughfare of Rainier restricts drivers to 30 mph. At the same time, I recognize my personal frustration may be a 1) psychological or 2) a perfectly legitimate price to pay for the greater environmental/safety good. The trouble I’m finding is that lane diet advocates focus on issues that opponents don’t care about – traffic safety, lowering speeding – while ignoring what drivers do care about – increased congestion, increased driving time, having to use side streets. What I would like to see is some old-fashioned cost-benefit analysis.

For instance, on Fauntleroy in West Seattle, the lane diet caused commuters to lose between 5 and 76 seconds of time on a 1.3 mile stretch of the road during peak traffic hours. That doesn’t sound like much, but it adds up to 12,000+ wasted hours per year and (valued at $17/hour) a little over $200,000 in people’s time (not to mention the wasted gas at slower speeds etc…). Additionally, there are no studies on how traffic on surrounding streets is affected as some drivers choose to take alternate routes. I could easily see this cost being outweighed by the benefit of more bicyclists, lower commute times for bicyclists, fewer accidents and injuries etc… but I haven’t really seen an effort by pro-bike folks to do this.

If folks could point me to any studies that do a thorough weighing of comparable costs and benefits, it’d be great. I am eager to be persuaded and join the pro-bike majority, but I’m having trouble getting over this hump. Know I’m late to the party on this post but would appreciate some educating from any bike lane advocates who have the time.

Thanks!

“The trouble I’m finding is that lane diet advocates focus on issues that opponents don’t care about – traffic safety, lowering speeding”

The fact that they don’t care about those things completely voids their opinions. If you are willing to sacrifice the lives and limbs of your fellow citizens so you can go a little faster your priorities are off (and you might be a sociopath).

“Fauntleroy in West Seattle, the lane diet caused commuters to lose between 5 and 76 seconds of time on a 1.3 mile stretch of the road during peak traffic ”

Source? And is that time lost because of congestion or because average speeds have lowered to approach the limit?

Hey Leif,

The Fauntleroy source is a Seattle DOT 2010 traffic report study. I’d imagine that speeds have slowed because other cars are in the way (rather than out of driver preference) but the study doesn’t say.

http://www.seattle.gov/transportation/docs/2010%20Traffic%20Report%20final.pdf

Regarding your dismissal of a “sociopathic” focus on traffic speed over safety, I disagree that looking at tradeoffs between time/freedom and safety is sociopathic. If we made the speed limit 5 mph and coordinated all driving through an automated system, that would probably save lives and reduce injuries. However, that would make everyone poorer, waste everyone’s time and create a worse society. This is obviously an extreme example, but it demonstrates that there are sometimes tradeoffs between freedom and time on the one hand, and safety on the other, and that I’m interested in learning more about what these tradeoffs are for “lane diets.”

For Fauntleroy, what are the choices? Should bikes be routed to another street? Which one? If bikes stay, how do you provide space for them (especially at 35mph)?

The Broadway case is different than Fauntleroy. It was slow before the changes and I’m not sure the changes have made a difference (but that is completely unsubstantiated). However, I will say, that it is not a good choice if you’re trying to drive through from, say N cap hill to Dearborn. Pick a different route – 24th or Boren, etc.

California ave would be more similar to Broadway. At some point, more space might need to be made there for rail, bikes, peds. If so, *through* auto traffic will need to be routed to some other street.

I drive a car sometimes and totally understand the frustrations of getting stuck in traffic. At the same time, I support efforts to move away from the auto centric design of the ’50s and ’60s. It’s just not a sustainable model unless population growth freezes.

Hey Paul,

I hear you big time on moving away from an autocentric city model. Ideologically, I’m a strong supporter of proactive funding of driving alternatives like light-rail, subways etc… I’d be happy to pay an income tax to fund it. What bothers me is when government tries to make certain legitimate activities unpleasant or illegal to discourage them (which is what I believe Seattle is doing with driving). Instead of lane shrinking, making parking more difficult and slowing down traffic, we should raise taxes for public transportation and introduce a small carbon tax (w/ refunds to low income families) to provide people with attractive alternatives. I think leaving more freedom in the hands of individuals is important.

Regarding Fauntleroy, I’m honestly not very familiar with the area (was just looking for relevant data). Looking at a map though, why not make 41st or 42nd Ave a bike thoroughfare? With Broadway, I understand that things are tricky because of crossing Olive and Pine, but I still feel like you could put something on a low traffic road like Harvard or another side street and make it work with stopsigns/lights. I do feel like the specific targeting of these high volume roads for lane shrinking is in part a deliberate attempt by the city to discourage drivers rather than encourage driving alternatives.

Also, the reason I’m posting is to potentially find a rational argument that will outweigh my frustration with congested traffic and longer travel times. My hope is that “lane diet” advocates can show me a study saying the benefits outweigh the costs so I can become a lane shrinking supporter.

If your concern is congested streets in general those selected for rechannelization aren’t the ones you should be focusing on. Rechannelized streets are specifically selected because they are over-engineered. They have more lanes than needed to support the traffic volume. The streets are generally four lane, with two general purpose lanes in each direction. This design encourages speeding (natural human reaction to driving in wide open area). When they redesign the road it can still accommodate the same vehicular volume, but the speeds naturally lower to closer to the limit. Whether the speed limits are appropriate or not is up for debate, but I hope that you agree that adhering to the posted limits is a positive outcome. In addition to increased safety, rechannelization can provide other benefits to drivers. The new center turn lane makes left hand turns much easier and less stressful. Sometimes parking can actually be added.

I’d guess that the increase in travel time on Fauntleroy is not so much because the rechannelization caused increased congestion, but more a combination of decreased travel speeds, increased volume (the report notes a slight rise), the addition of a couple crosswalks, and the addition of bus bulbs. Bus bulbs make the public transit system work a lot better since buses can serve a stop without having to exit and reenter traffic. Most of the time this doesn’t slow down traffic too much, but it certainly can when there are a lot of transit riders or the bus needs to serve people in wheelchairs.

The point being, before the redesign the street was engineered almost exclusively to serve single occupancy vehicular traffic. With a “complete streets” redesign the street now has facilities to serve drivers, transit users, bicycles, and pedestrians. The distribution of space still reflect the fact that SOV traffic is the primary user, but now there is room for those who want to use other modes.

I disagree that when these choices are made it is done so with a malicious intent of making driving unpleasant. But since there is only so much room in the city there is no way to accommodate all users in such a way that everyone can have a completely unencumbered trip. And even if every road was designed to maximize vehicular efficiency at the expense of all other users, the number of people driving would naturally increase and create more congestion. In an urban environment it just isn’t possible to build your way out of congestion.

Two last thoughts:

First, remember that the vast majority of people you see on bikes, on foot, or in buses are also drivers sometimes. I own a car and drive it often, I’d rather there be more/better/safer options for me to walk/bike/bus/train, but even when that happens I’ll still drive a car for some trips.

Also, something to keep in mind when you are stuck in congestion and getting frustrated: you are traffic.

[…] you moved to the north end of Seattle after the summer of 2011, you may have no idea that there was an epic debate over city plans for a road safety project on NE 125th Street. That’s because the project, […]

[…] he exhumed the “WAR ON CARS” rotting horse carcass so he could kick it a few more times, just to illustrate his point. No, I’m not joking. […]