Imagine you have two major highways leading into your Pacific Northwest city. One comes from the south and goes all the way to Mexico, the other comes from the east and connects all the way to Midwest and Atlantic ports. It would be crazy not to connect them, right? I mean, your city could be the nexus of freeway travel. That’s a good thing, right?

Well, people from Seattle don’t need to try very hard to imagine this scenario, because we did it. We demolished entire neighborhoods, dug huge trenches, bore giant tunnels and built elaborate elevated structures to build and connect I-90 to I-5 right in and through downtown and nearby neighborhoods. Protests to “Stop the Ditch” were ignored.

This was the vision of progress at the time, and cities all over the planet were doing the same things. And Vancouver, BC, was no exception to these kinds of plans. But Vancouver residents and leaders were able to see first hand what freeway construction means for neighborhoods by looking at Seattle. And it was devastating.

So Vancouver made a decision that probably seemed insane at the time: They chose not to build and connect freeways through their city. And that may go down in history as one of the greatest choices any US or Canadian city made in the 20th Century (thanks to Gordon Price for the great Vancouver freeway history lesson during a Commute Seattle study trip earlier this month).

Today, Vancouver’s economy is booming. And there are plenty of cities that built complete freeway networks that are really struggling (I should know, I grew up in St. Louis). So don’t buy for a second that in-city freeways are needed in order to have a strong economy.

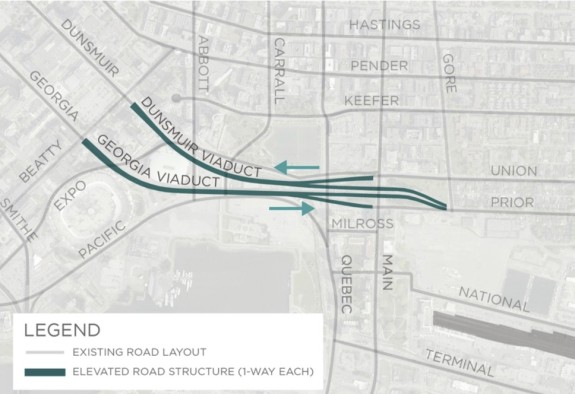

But they did build one piece of their planned-then-scrapped freeway system: Elevated viaducts just east of downtown connecting to Georgia and Dunsmuir Streets. But the freeway connections never came, and now these viaducts are vulnerable to earthquakes.

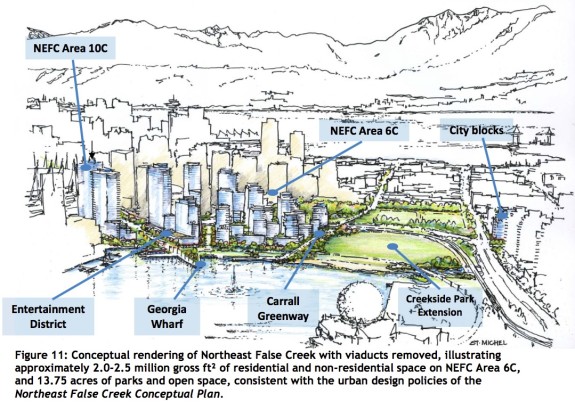

Like in Seattle, Vancouver has debated about what to do with the viaducts for a long time. And this week, the City Council voted 5–4 to tear them down. Instead of viaducts, the city will create a new neighborhood-scale street grid, open space for new homes, and build a big new park at the far end of False Creek (see the plan in this PDF).

Why am I writing about this? Because it represents such a drastic difference in the way Seattle has been planning its future. Our downtown has two highways through it, and even our plans to finally remove the lesser of the the two includes a new giant highway tunnel. There are talks of building a lid over parts of I-5, which is cool. But it’s clearly not yet a priority for our city and state leaders.

Why am I writing about this? Because it represents such a drastic difference in the way Seattle has been planning its future. Our downtown has two highways through it, and even our plans to finally remove the lesser of the the two includes a new giant highway tunnel. There are talks of building a lid over parts of I-5, which is cool. But it’s clearly not yet a priority for our city and state leaders.

We remain trapped into thinking of highways as the primary way of accessing our increasingly dense central neighborhoods. We simply can’t see beyond our freeways. There’s support for building more transit, but mostly only as an add-on to our car-driving network.

Meanwhile, Vancouver has barely managed to pass a vision of their downtown where homes, parks and connected people-scale streets are more important than unimpeded car movement. Even in a city that doesn’t have freeways, it was a hard sell. Once separated highway infrastructure is in place, it’s really hard for people to imagine their city without it.

Vancouver isn’t a perfect place. It has housing problems, too, as it struggles to keep up with growth. There are still major barriers to walking and biking and gaps in its transit system. And more than half of trips are still made by car (ironically, not having freeways means the traffic load can flow across a connected street grid, helping to prevent traffic jams).

But it’s a fascinating case study to compare with Seattle. And this week seems like an important moment in history for our neighbor to the north. So big congratulations! I can’t wait to take the train up there in 2020 to check it out.

Comments

12 responses to “Vancouver BC will tear down its only freeway remnants, replace them with more city”

Oh, we can see a Seattle without the Alaskan Way Viaduct, failed, ill-timed, poorly messaged vote to stop the tunnel aside. But the people at the Washington State Department of Moving Automobiles that have probably never been in Seattle for more than a day or two at a time sure can’t.

Not sure the point of your comment. Many WSDOT staff work and live in Seattle. Did you think they all work in Olympia? Not to mention, it wasn’t WSDOT that selected the tunnel, or has the power to decide to build any freeway. That falls on the policy makers. We are getting the tunnel because our elected leaders wanted it.

Seattle also made the blockheaded decisions to 1) Choke down I-5 to two through lanes downtown and 2) Build the convention center over the choke point so additional elevated lanes could never be added.

Did Seattle really need a freeway going through it? I like to imagine what it would be like today without that long scar, slicing once contiguous neighborhoods in half. Would downtown have suffered urban rot? Maybe, but there are other factors. Would we have had the 1968 subway system? Almost for sure.

As it is 405 is becoming I5. It is growing wider and wider where I5 is not. Eventually 405 may be the main route for through traffic.

If you’ve ever driven on 405, you’ll know that it’s still MUCH better to go I-5, with its two lanes, than 405.

Freeway planning in the 50’s assumed people would commute from the outer suburbs to work in the downtown core. The idea that people would chose to live on the opposite side of downtown from where they worked wasn’t considered. The convention center isn’t all that limits widening through the downtown core. Recall that the “pinch point” existed before the convention center was built. Back in the 50’s, in the downtown area, the City of Seattle only agreed to a certain width of Right of Way for condemnation (I believe it was 300′). This constraint resulted in all the exotic, stacked express lanes in this area (in contrast to the wider, side-by-side arrangement north and south of downtown). So even without the convention center, the State would need to additional property to expand, and the cost of that land – especially today – would be prohibitive.

This is a really interesting post and I appreciate that overlay of I-5 on the aerial photo of the city.

It’s true that the city council voted (5-4, with two absent) to remove the viaducts. But to say that Vancouver “will” tear them down may overstate the reality, as there is suddenly push-back from the provincial government, which seems to make a habit of attempting to embarrass Vancouver city (and lower mainland in general) government at any opportunity. See, for example, this CBC article headlined “Vancouver viaducts’ removal was discussed with province, mayor claims”:

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/viaduct-removal-robertson-responds-1.3293603

It’s an ugly situation, but not really a big shocker.

The only thing I’ll miss here is the properly protected bike lane on the Dunsmuir Viaduct (also shown at the top of this post, obviously).

The final plan isn’t finalized of course but the preliminary plans I’ve seen include a walking and cycling ramp up to Dunsmuir from Carrall St. Likely south of the Skytrain.

The new ramp up to Georgia St. currently shows painted bike lanes on each side. (I hope they can find the room to make them protected lanes though.)

http://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/viaducts-study.aspx

Thank you for including the map of 1963 Seattle. Unfortunately, it does not show the ORIGINAL, grandiose I-90 proposal: 14 lanes sprawled from I-5 across the central area, a cut and (maybe covered) thru Mt. Baker ridge onto bridges parallel to the old Mercer Island bridge. I have a copy of this original nightmare. Your overlay shows the scaled version that resulted from years of oalition building, lobbying and legal action across the city. I am proud to have been a part of the diverse coalition of citizen activists who stopped the 15 mile RH Thomson and elevated (S. Lake Union) Bay Freeways and changed city council’s responsiveness to ordinary citizens and the laws under which they are supposed to operate. If only more of this information was available at places like historylink.org and crosscut.com, it could inspire today’s urban activists!! Thanks for listening.

[…] a flourishing example of a similar city that did not build urban freeways. They are now working to remove the only freeway-like remnants they built in order to build more city in its […]