Yesterday in Part I, we reported on a protest at City Hall over the city’s delayed bike plans, especially downtown. In Part II, we look at how Seattle got so far off their bold safe streets path, and how the city can get back on track.

How did we get here?

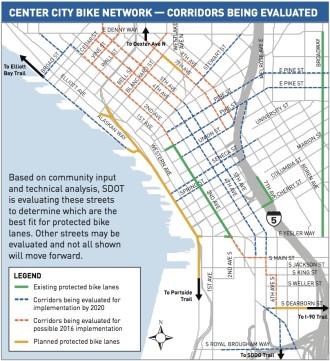

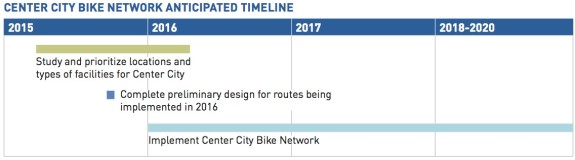

SDOT hosted an open house last July showing the concept and timeline for a network of downtown bike lanes they called the Center City Bike Network. Over 100 people attended, and from what I could tell everyone was in favor of the plan. In fact, the only consistent complaint I noted in my post afterwards was, “Why isn’t this moving faster?”

The open house showed a handful of corridors being considered for 2016 implementation, which at the time was already a frustrating delay for people hoping to have bike connections completed in 2015.

The corridors studied for 2016 included complete connections to both the north and south, SDOT just didn’t know which exact routes would be picket yet. The basic takeaway: Wait just one more year and the 2nd Ave bike lane will finally be connected, and pass Move Seattle if you want the rest of it to happen.

Now we are heading into summer 2016, and there are no plans for any of these corridors to be completed this year. The city passed Move Seattle, yet the bike plan is getting shorter, more fragmented and more delayed. Worse, city transportation leaders are acting as though no such promises were ever made.

“The 2015 plan reflects unstudied but [Bicycle Master Plan] prioritized corridors in CC from 2015 to 2019,” SDOT spokesperson Norm Mah wrote in an email to Next City’s Josh Cohen. “Based on evolving nature of the center city, SDOT did not make a commitment to having all the [Center City Bike Network] construction complete by 2020.”

That’s why people are protesting. To hold city leaders accountable and provide them the political support to make bold decisions that put safety above all other transportation priorities as leaders consistently claim.

When Mayor Ed Murray launched Vision Zero in early 2015, he made a commitment to put safety first and to take bold action to make Seattle’s streets so safe that nobody will be killed or seriously injured in traffic by 2030. And the people were behind him. Now as the effective boss of SDOT, he has to deliver. The first half of 2016 has been a dismal failure for safe streets progress. If he doesn’t turn this around, that City Hall protest energy from Tuesday will likely turn on him.

How to get back on track (and maybe save some lives, too)

Mayor Murray has demonstrated his ability to take bold, fast action on safe streets even for complicated projects. We saw this on 2nd Ave and even Rainier Ave.

The 2nd Ave pilot project was announced in May 2014 and open in October that same year. If he wants SDOT to complete basic 2nd Ave connections this year, he could make it happen. SDOT staff can handle it, they just need the order.

Do that again, Mayor Murray! Direct SDOT to connect the existing 2nd Ave bike lane:

- north to Dexter and the new Westlake bikeway

- south to Dearborn

- east to Broadway (or at least to the existing bike lanes that start at 9th and Pine)

- west to the Alaskan Way Trail entrance at King Street (it’s almost there already)

And direct SDOT to have them all be open by October.

Councilmembers Rob Johnson and Mike O’Brien urged SDOT during the committee meeting to consider using low-cost materials to get more bang for each buck and get bike lanes connected faster. Then the city can go back and make them permanent later when they get funding or when that street is repaved.

“I hear people say, ‘You built this beautiful chunk, but when I get to the end of it I don’t know where to go,’” O’Brien told SDOT staff during the committee meeting. Completing the connections is vital, and a partial bike lane that disappears can be worse than no bike lane at all.

Using low-cost materials also gives the city wiggle room to modify the bike lanes if needed in order to help move buses in 2018. So this work can occur in parallel with the Center City Mobility Plan instead of waiting two more months to start design work. As Councilmember Kshama Sawant pointed out during the meeting, people need safe streets and better transit.

“I don’t want resources for biking and transit to be pitted against each other,” she said. This is true both for funding resources and physical street space.

All the pieces are in place for Seattle to innovate and lead the rest of the nation. Sure, the rate of building construction in South Lake Union and downtown poses a problem for building a bike network. But the economic power behind that construction and growth is a big reason Seattle has the resources to innovate and create this fully-connected downtown bike network.

And biking is a big part of the solution to accommodating more jobs and residents in a finite amount of space. So the city cannot delay its bike plans to allow growth, because the city cannot grow if people drive to their new center city jobs and homes.

SDOT staff told the committee the department will develop rules for providing safe bike access during construction closures as they did recently for walking. In the meantime, they will “actively manage” construction along bike lanes, highlighting 9th Ave N as such a route. So the city is committing to build 9th Ave N on schedule this year, not delaying it until 2018 as was announced during a recent Bike Board meeting (another win from this recent public pressure, though we will need to keep an eye on this project).

Burn the 2016 short-term bike plan

As for my suggestion for the 2016 short term bike plan (“burn it and try again“), SDOT seems to be meeting half way. Staff said they would start working on the 2017 update in July when the Mobility Plan releases its bus movement analysis, just a few months after the 2016 plan was released.

This is good news. SDOT staff who made the 2016 plan are great, but they were forced to create it within absurd parameters:

- Bike lane mileage was calculated at a high cost-per-mile rate, resulting in big cuts in mileage. Instead of slashing miles, it would be better if SDOT developed a plan to deliver more for less (perhaps by using more cost-effective methods or finding ways to split project costs with other budgets. If a new traffic signal also helps walking and driving, for example, why should the cost come entirely from the bike plan budget?).

- No projects combined bike lanes and neighborhood greenways, leading to some strange neighborhood greenway routes since many of the most promising routes require at least some sections of bike lanes on busier streets. Rainier Valley was probably the biggest victim of this. People don’t care if they are on a safe neighborhood street or a safe bike lane so long as it is all direct, intuitive, connected and comfortable.

- Few projects connected high-demand areas and other high-demand areas. Seattle Neighborhood Greenways highlighted a different way of viewing connectivity goals in a recent guest post.

- Most baffling of all, the plan pretended that downtown Seattle does not exist. That’s just not true. You can’t create a bike plan that makes any sense by ignoring the biggest destination center and bike route nexus in the whole city.

Don’t ‘frustrate our allies’

As a closing note to the meeting, Councilmember O’Brien urged SDOT to communicate clearly about the status of safe streets projects. When the city releases a plan that slashes the city’s safe streets ambitions without any warning or clear explanation, people are going to feel misled, abandoned and angry. That’s exactly what happened with the 2016 short term plan.

“I think that’s our job as a city to not frustrate our allies,” O’Brien said.

The plans released in 2015 represented an ambitious, bold and innovative vision for safe streets and bike mobility in Seattle. That vision inspired people to work hard for the Move Seattle levy campaign, which passed despite internal polls showing it going down in flames (the ground game was likely a big part of the difference).

Was the 2015 plan over-ambitious and unrealistic? I’m not so sure. If SDOT staff had the green light to innovate and make it happen, I believe they could do it.

But the consequences of not even trying are horrible. Our neighbors, coworkers and loved ones are getting lifelong injuries or even killed just for trying to get around our city. We can end traffic violence, but only if we take action. Planning documents will never save lives unless we use them.

Comments

13 responses to “We Can’t Wait, Part II: How Seattle’s bike plans got so lost, and how to get back on track”

I admit, I feel pretty angry that the city promised some reasonable projects and now has cancelled many of them without even a snip of communication.

Besides doing the projects, where’s the maintenance? Bike lanes and sidewalks get filled with debris over time. Nothing seems to get cleaned. Here are two examples:

– fremont bridge approach, north side. Someone spilled a lot of sod and soil on the side walk (I suppose from a passing truck) a few months ago. Bit by bit it has been worn down to a string of clumps along the railing. Even with this being a high focus route, absolutely nothing has been done to clean up the mess.

#2 Aurora bridge sidewalks. It’s been at least 2 years since they have been cleaned. There’s a significant deposit of silt and other debris on them and, when wet, becomes quite slippery. To some credit, as part of the bridge restoration work, I recently saw a worker scraping up some of the debris in the vicinity of his work. That helps but I wouldn’t call it cleaning.

I think we have a very fragmented bicycle infrastructure management. There seems to be no cohesion, no one with driving force, no one to make sure the system is working.

Yes, maintaining what we have is one of my primary concerns. If you think it is bad in the north end of town come down to Georgetown or the Duwamish to see a littered bike lane or trail. This city is all about the north end when it comes to biking.

Blackberry vines growing into trails also completely predictable but only seem to get dealt with on a complaint/reaction basis. I always wonder if somebody has a pruning and sweeping plan at all.

My commute includes two different trails with woefully inadequate maintenance.

I carry pruning shears on my commute at least once a month spring and summer, but it sure would be nice to see a formal pruning schedule and maybe more competent planning of what to plant next to traveled paths.

Definitely report this stuff! I know for arterials SDOT has a street sweeping program, but it doesn’t happen very often. That means debris that ends up in a bike lane will sit there for months until the next scheduled cleaning. If you report it, it may take a week (or two), but SDOT will clean it.

I haven’t heard of anything regarding regular maintenance/cleaning of PBLs. It’s definitely something that needs to be addressed (and if there is regular cleaning, it’s not often enough).

I wish it were true. I have reported the Aurora bridge several times. Like I said, it’s been at least 2 years.

Is Aurora maintained by SDOT, or by WSDOT since it’s SR 99?

I believe SDOT operates the Aurora Bridge, though the state owns it. But I’m not 100% sure which agency is in charge of what.

I have actually had pretty good luck with the city’s Find-it-fix-it app on my phone. Snap a photo of the problem and the submitted form usually gets a response pretty quickly and some kind of action on the street. What is nice is that it generates a ticket in their system that someone has to respond to before it can be closed.

Will that work for street cleaning? I’ve used it to report pot holes and, for that, they do respond quickly.

When I see the quality of bike infrastructure built and maintained by King County I really wonder if there isn’t a way to transition SDOT’s bike/ped money to them to build and operate, similar to our transit.

As a tax payer I would much much much rather give my money to Dow and Taniguchi than Murray and Kubly. I almost wish Ballard would leave Seattle and be an unincorporated part of King County so we could get decent public service and some basic accountability.

Or even better, go back to being its own city like it was a century ago.

Which infrastructure are you talking about here? The county-maintained parts of the BGT? Those are parks-maintained and exist thanks to a once-in-a-generation dedicated ROW opportunity. In the parts where it does interact with the street network it often suffers from ambiguous or bike-hostile right-of-way scenarios, inviting nonsense like the Lake Forest Park PD’s ticket stings on cyclists (often riding perfectly safely but breaking the letter of the law).

Most of what we build going forward will rely on streets ROW. What’s King County doing that’s so great with street ROW in unincorporated places like White Center?