Seattle’s plan to lower default speed limits across the city heads to the City Council’s Sustainability and Transportation Committee today. The plan — which has support from the Mayor’s Office, SDOT and the City Council — needs to make it through the committee and the full City Council before getting the Mayor’s approval and going into action. If all goes smoothly, that could be as soon as November.

Seattle’s plan to lower default speed limits across the city heads to the City Council’s Sustainability and Transportation Committee today. The plan — which has support from the Mayor’s Office, SDOT and the City Council — needs to make it through the committee and the full City Council before getting the Mayor’s approval and going into action. If all goes smoothly, that could be as soon as November.

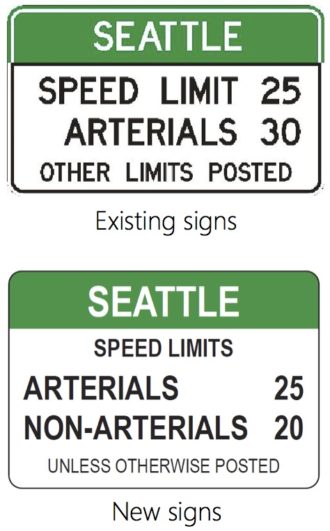

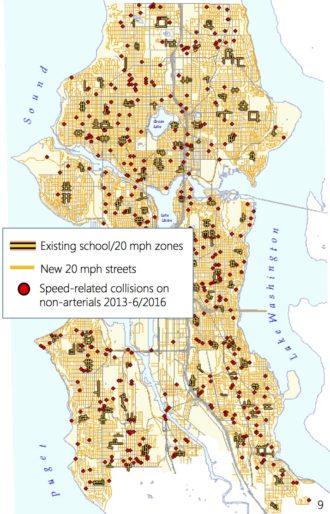

That change itself is pretty simple, but the implications for safety could be huge as we reported when it was announced. All it really does is change a bunch of signs near the city limits to spell out the new default speeds. For “non-arterial” mostly residential streets, the default limit would be lowered from 25 to 20 mph. For busier “arterial” streets, the speed would drop from 30 mph to 25 mph unless marked otherwise, as is often the case.

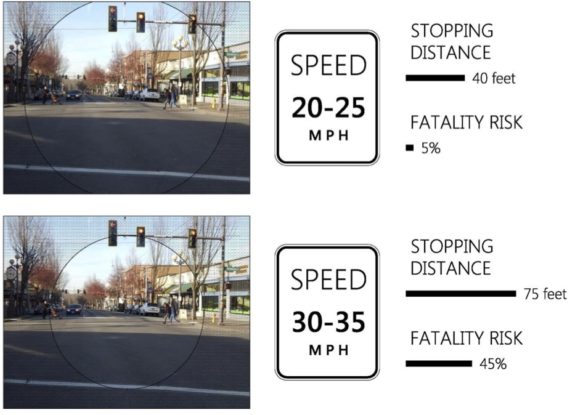

But when speed limits are lower on a street (and people know about the limit), the majority of people who want to follow the law will limit their top speed to that new limit. And that alone could improve safety, according to a city legislation document (PDF):

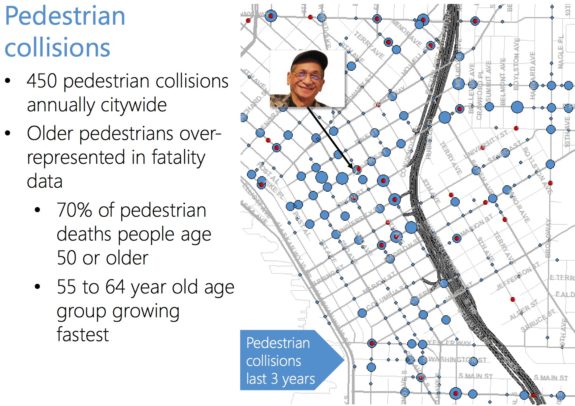

More than 10,000 collisions occur on Seattle streets annually. Less than 10 percent of these crashes involve pedestrians, bicyclists or motorcycles yet these modes make up more than 50 percent of fatalities. Vehicular speed is often the critical factor for survival in collisions. The higher a driver’s speed, the greater risk to vulnerable road users.

Most of the big streets obviously designed for faster speeds (Aurora, for example) have their own marked speed limits and will not be affected by this change. Those streets will need targeted road safety projects before speeds can reasonably be expected to drop. Move Seattle provides funding for about one “road safety corridor” project every year.

Such a change will have hardly any effect on how long it takes for someone to get from Point A to Point B, but it could have a big effect on the top speed their speedometer reaches during that trip (before slowing again for traffic or another red light).

With even modest drops in the top speed, fatal or serious injuries turn into bumps and scrapes, bumps and scrapes turn into near misses (and maybe a honk), and near misses don’t happen at all. Little is gained by going 30-35 instead of 25-30, but a lot could be lost.

This change not only protects public health, but it makes the walking and biking experience more inviting, encouraging more walking and biking trips that may otherwise have been driving trips.

And in case you think Seattle is being radical with this change, note that Seattle is currently the only city in King County with a default speed limit higher than 25. The city set the 30 mph limit in 1948 during an era when many dangerous traffic decisions were made (bridges without space for walking, freeway-style infrastructure in neighborhoods, etc). It’s time for a change.

Stay tuned for updates from the committee meeting starting at 2 p.m.

Stay tuned for updates from the committee meeting starting at 2 p.m.

UPDATES:

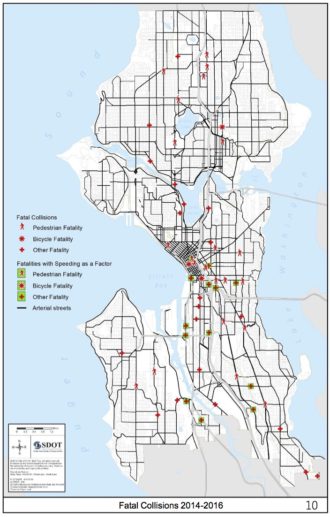

When looking at maps covered in collision, injury and death data, SDOT Director Scott Kubly wanted to remind everyone that “there are real people behind each one of these dots.” This is such an important point to make, and it gets glossed over so easily when confronted with an overwhelming dataset like those posted here.

Most of the arterial streets that do not have posted speed limits at the moment are in the center city, so that’s why the city is focusing their outreach on that area. Arterial streets outside the center city mostly have their own posted limits and will not be immediately impacted by this rule change.

The city does not want to go out and just arbitrarily lower those speed limits, preferring to go corridor-by-corridor and couple speed limit changes with appropriate design changes.

“We want to design a road where you’re naturally going the speed limit,” said Kubly. If you have a really wide street with few impediments to driving fast, lowering the speed limit will do little to change behavior. Traffic calming and modern safe streets designs are vital to reaching our safety goals. Changing the limit isn’t going to get there on its own.

We will also continue to follow our standard enforcement protocols, developed with community help. People will get warning for a few weeks after the change goes into effect.

The city will still need to study speeds on a street to determine whether 85th percentile speeds are close enough to 25 mph to lower the speed limit. It was not entirely clear during the meeting if such a study is currently required by state law or not. Councilmember Rob Johnson found this limit frustrating.

“The only thing that’s frustrating me about this legislation is the lack of implementation outside of downtown quickly,” said Councilmember Johnson.

The legislation passed unanimously and heads to the Full Council meeting either next week or the week after.

Housing > Parking

Another topic on the docket for the 2 p.m. meeting: A very boring-sounding Parking Benefits District that could actually be one piece of a big housing affordability mindshift. The need (or perceived need) for protecting private access to public car parking spaces is a huge impediment to building more homes in our neighborhoods. But we need to reframe the role of public car parking spaces so it is not in opposition to new homes.

Sightline explains how a Parking Benefit District could help the other HALA policies and why the city should at lease try the idea:

The reason HALA ranked the Parking Benefit District pilot so highly is that parking rules bloat housing prices, and PBDs are the most promising political strategy for changing parking rules. I’ve spelled out this argument in other articles (the crux is here), but I’ll summarize.

Eliminating existing requirements currently on the books in almost every city, namely that housing builders install lots of off-street parking spaces, is a key strategy for housing affordability. Most people wouldn’t guess it, but parking requirements (or “quotas”) raise the rent—and not just by a little, but by a lot. Here’s a full rundown of how they do so, but some major ways include:

- Parking quotas raise the cost of building housing, especially inexpensive housing, and they suppress the number of apartments and houses that can fit on a lot—often by a quarter to a half.

- Parking quotas block adaptive reuse of old buildings, such as vacant warehouses, to housing.

- Parking quotas disperse housing by suppressing housing units per city block, which exacerbates sprawl and therefore distances traveled, which makes transit less practical and driving more common. And driving is expensive.

At Seattle apartment and condo buildings, the cost of parking is as much as 35 percent of monthly rent, even for residents who do not use a parking space. And this estimate does not include the way parking mandates suppress the number of apartments citywide, which leads to more price competition for each of them.

UPDATE:

This issue turned into a rather interesting debate about parking revenue during the meeting. SDOT staff have been very effective at implementing an exceedingly data-driven parking management system since 2010. In some ways, maybe we shouldn’t disrupt this success by introducing other factors.

But the biggest piece SDOT staff have on their side about the revenue destination (the general budget vs a parking benefit district) is that keeping the funds in a district could be at big risk of being distributed inequitably. Right now, investments can be distributed through the departments regular process, which includes an equity analysis. If the money stays in a district, it sort of goes around that analysis.

Councilmember Kshama Sawant also made the claim that parking meters are a regressive way to raise revenue. In one way, that’s true: Everyone pays the same cost for an hour regardless of their income. But car ownership is very much correlated with income, so usage fees for car use are really at least somewhat progressive.

One interesting hint came up during the meeting: The parking crew is looking at the city’s Residential Parking Zone program. I’m dreaming of income-based fees for an RPZ pass…

Comments

14 responses to “Seattle’s safer speeds plan heads to Transpo Committee + Housing is more important than parking”

What about the state highways that run through the city? There’s a section of Sandpoint Way that’s currently 40mph and has little to no shoulder, and a sidewalk only one side. It’s a death trap for bicyclists. Luckily the BG Trail parallels that area, so not many bikes/peds are on the road, but still.

https://goo.gl/maps/TK4FKg36q242

Had no idea that section of Sandpoint was 40 mph. It really should not be more than 30. It is my preferred way to get to Magnussen fast by bike, especially on weekends. Never had any personal issues there, but I’ve never ridden it during rush hour. At night I would take the BGT.

Keep asking SDOT, the Mayor, and City Council to fix that ridiculous highway. Note that part of the 40mph stretch is owned by WSDOT, but only part of it.

The Parking Benefit District thing doesn’t make sense to me. It seems pretty tenuously connected to parking quotas. People who live in neighborhoods have access to cheap RPZ parking, so they won’t be paying the meter rate anyway. So, cutting down parking quotas wouldn’t generate much more revenue through parking meters…

I think a better idea would be to require buildings to rent out their extra underground parking to the public, rather than keep it all private for residents. This way we could keep the same parking quotas, but instead of residents paying for it, visitors to local businesses would subsidize it. It’s not a perfect solution, but probably more politically palatable than reducing parking quotas.

So the city is cutting ties with district councils because they’re unrepresentative. What of the groups that would receive PBD funds? Is there any reason to believe they’d be different in the long run?

“If you have a really wide street with few impediments to driving fast, lowering the speed limit will do little to change behavior.”

Correct. I have very few bones to pick with the Safe Streets work of Scott and Dongho, but one of them is 15th Ave W between Armour and the Ballard Bridge. The limit here was dropped to from 40 to 30 mph a while ago, but the street was left unchanged as one of the few vestiges of the otherwise-unbuilt six-lane 1967 Northwest Expressway. If you actually drive 30 mph here, other drivers will be honking and swerving past you.

It’s the only place in Seattle where I drive above the limit, as I think it’s safer; and I’m not going to get a ticket anyway, as even at 35-40 mph I’m still one of the slower cars on the road. (For the record, I’m fine with the decision to drop the limit from 35 to 30 south of Armour).

Meanwhile, as others have pointed out, some arterials that aren’t actually built like freeways, and which have actual humans you could crash into and kill on their sidewalks — Sand Point Way, the north end of Aurora being the best examples — have 40 mph limits. Dropping these citywide limits is laudable, but the change is only really meaningful on residential streets, where twenty is plenty, and always should have been.

Speed Limit signs don’t do diddly; Seattle continues to push the “quick fix no thought” solutions. It’s really disappointing how little our infrastructure has improved in the last five years in alternate transportation (verse other cities like Portland and Vancouver, BC).

“But when speed limits are lower on a street (and people know about the limit), the majority of people who want to follow the law will limit their top speed to that new limit.”

I and any other person who has ever driven in this city would very much beg to differ. That statement is either (1) false, because even people that want to drive the speed limit don’t because traffic is moving way faster or (2) true, but there are like 5 people in the entire City that want to drive the speed limit.

I include anything within 5mph as “driving the speed limit,” since that is basically accepted practice and tickets are very unlikely at that speed. I think most people don’t generally feel comfortable exceeding that, though they will on multi-lane roads if the flow does (something like speeding critical mass).

That’s one more great thing about not having two or more lanes in the same direction: The people driving responsibly set the pace, not the people driving fastest. There’s not much social pressure to speed if people aren’t passing you. But once you starts getting passed, you feel like you’re an impediment so you speed up. That’s a dangerous cycle.

Very true. Living in Ballard, when I do drive, my options to leave are Market, 15th or Leary (all 30mph). If I’m actively paying attention to my speed and there’s not a lot of traffic, I can very easily keep it below 35.

However, once you throw in traffic flow, left/right turners, bicycles, pedestrians, street lights, parking lanes, etc, to where I don’t actively monitor my speed, I regularly find myself exceeding 40 mph or even approaching 50 and have to ease off the pedal, usually to the frustration of the person behind me.

I don’t want to speed and I don’t mean to speed (ultimately, there’s no excuse), but traffic works like a herd of sheep, and if no one is herding them, they can get into trouble. It just frustrates me to no end that the City is like eighth-assing this opportunely to really make an impact in safety. When they say things like “We will also continue to follow our standard enforcement protocols…”, it’s extremely clear that this is an exercise in futility, but an excuse to pat themselves on the back for a job well done…

I can only wonder if this lower of the speed limit with no enforcement could lead to a lawsuit against the City, when inevitably someone gets run over by a driver doing well over the lowered speed. You’d probably have to prove regular non-compliance with the lowered speed and lack of the City to enforce it, but that could all be done.

“The people driving responsibly set the pace, not the people driving fastest. ”

Yup, and it’s a fun form of character-building to ignore the moron 5′ behind and do the right thing.

Getting speeders down below 35mph will be a big help.

What would help even more would be brutal and ruthless application of tickets to speeders. 10% over is as much as should be tolerated, easily within the ability of an attentive drive to follow.

A self-funded traffic policing system with the costs divided among subject idiots would be a fine way to concentrate minds on speedometers.

The problem with a self funded enforcement is that you risk a system that starts to punish those on the fringe of committing violations. Going 2 over, stopped one inch post the stop bar, etc. I’d rather enforcement be funded from the general fund with ticket fines going back into the general fund.

Sorry, but this is false: individuals will, and will continue to, exceed the speed limit at the same rate regardless of the speed limit change. This is a politician attempting to score points for votes, that’s it. do I support the change? absolutely. But lying to your readers by stating citizens will start to drive slower? Please……Let’s stop lying and start being real: speeding will continue to occur at the same rate. However, what will change is how the city reports speeding in the future, which could potentially put Seattle in line to receive additional funds for infrastructure changes (since most of our funding is non-existent, or wrapped up in lawsuits and union contract negotiations, but I digress…)

What about speed bumps in high risk areas? If the drivers don’t feel it, they ain’t gonna change!