Rainier Ave needs bike lanes. There’s just no way around it. It’s the flattest and most direct way between Rainier Valley’s biggest business districts and downtown. The neighborhood cannot be truly accessible by bike without Rainier Ave bike lanes.

Today (Thursday) is the final day to complete SDOT’s online open house and survey about plans for the next segment of the Rainier Ave Road Safety Corridor project. If you don’t have time to complete the open house, Cascade Bicycle Club has also created a quick and easy way to email your support.

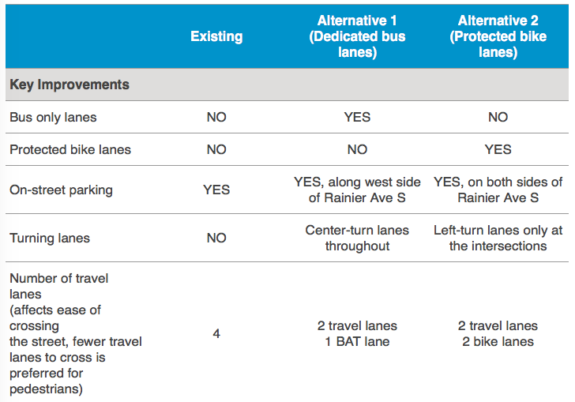

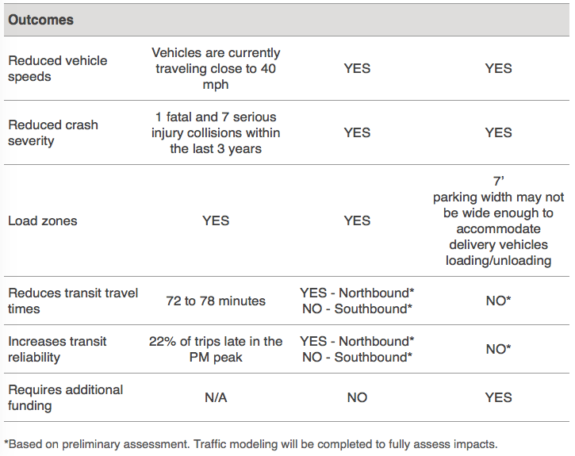

Unfortunately, as Martin Duke at Seattle Transit Blog points out, the city seems to be pitting transit against bikes with their two options. This is a false dichotomy. We need to prioritize both. It something is going to give, it can’t be bus ridership or street safety. I’m looking at you, on-street car parking.

Both options include on-street parking, and the bike lane option (Alternative 2) actually includes more parking than the bus lane option without bike lanes. Why is car parking mandatory in the city’s plans, but bus and bike lanes are optional? That’s completely backwards. Why not use some of the space for parking in Alternative 2 to instead help speed up buses?

Rainier Ave deserves an Alternative 3 that goes big and bold on safety, walking-friendly business districts and efficient transit.

As Andrew Kidde at the South Seattle Emerald notes, the benefits of Rainier Ave bike lanes on the new section could easily extend into at least part of the stretch north of the study area where the city conducted a safety project two years ago:

And the implications are even bigger — bike lanes could be extended up into the Phase 1 area with minimal effort. When SDOT repainted the lines for the Phase 1 road diet, they provided three 12 foot wide lanes. A car is 6 feet wide, and a 12 foot lane is the most generous size, typical for highways with 60 mph traveling speeds. Twelve foot lanes invite speeding, and have been associated with increased traffic fatalities. Indeed, why did SDOT choose to put 12’ lanes in a re-channelization project that had safety as its main goal? It’s a mystery. In any case, if these lanes were reduced to 10 feet with a simple paint job, there would be 6 extra feet of right of way in the phase 1 zone. Sounds like a bike lane to me.

Sounds like one to me, too.

Further analysis of the traffic safety data from Phase I of the Rainier project also backs up Kidde’s suspicion about the 12-foot lanes. Andres Salomon writes in the Urbanist that speeding really hasn’t gone down as much as it should have. So not only should Phase II aim to fix this oversight by making the travel lanes skinnier (bike lanes are a great way to do this), but that safer design should be extended into Phase I as well.

Ultimately, Rainier Ave bike lanes need to reach downtown. People should be able to hop on a $1 bike share bike to get between business districts in the valley or to get to work in our city’s biggest job center downtown. And they shouldn’t have to risk bodily harm or traverse steep unnecessary hills to do so.

Of course, building bike lanes on Rainier Ave will tap into much more difficult conversations about gentrification in Rainier Valley, where property values and rents are spiking through the roof even without hardly any quality bike infrastructure. During her primary campaign, Nikkita Oliver told Seattle Bike Blog she would have supported bike lanes on Rainier Ave, but urged people to focus on equity issues that could come with them:

As a project like this unfolds, I would also want to consider:

- Equity issues that come with bike lanes

- Displacement and “push out” in many Seattle neighborhoods have been preceded by particular types of neighborhood changes including the light rail and bike lanes. It is important to do this development with an intersectional analysis that understands who is most likely to ride bikes in Seattle, drive cars, and take public transportation.

- Since we know displacement is a possibility as these neighborhoods change we must utilize different community development strategies to preserve the culture and demographics of these neighborhoods.

- We MUST prioritize first those areas and streets where a) they are the most dangerous and b) bike lanes will actually provide the necessary safeguards to make our cyclist safer.

One idea she stressed often in her campaign was expanding bike education to help increase access to bike culture. I would add that new bike share services in Rainier Valley also provide a new point of affordable access to more people.

But when people are fighting to help themselves and other members of the community avoid what is essentially economic eviction, bike lanes are not often at the top of the list of needs from the city. The commodification of homes is a ruthless force, and communities of color are at particular risk of displacement. Even though biking can be a more affordable way to get around, bike lanes can also make a neighborhood more marketable.

On the other hand, preserving a dangerous street design that injures people at an alarming rate, contributes to poor air quality and discourages exercise is a terrible way to maintain affordability. And as we’re seeing, home prices and rents are soaring without any help from bike lanes.

On a larger scale, the same problem can be said for major investments like Link light rail, which certainly made Rainier Valley more marketable and accessible. How can the city make sure new investments in a neighborhood actually improve life for all people already living there rather than helping the housing market push people out? One solution for transit is to build affordable housing as part of transit-oriented development around stations. What affordability tools can we use to accompany bike lanes?

It’s criminal that our city is failing to build enough homes and invest in public housing at the rate needed to maintain affordability so existing communities are not displaced as the city grows. To a lesser extent, the city’s longstanding and ongoing failure to invest in safe and comfortable bike lanes and trails in Rainier Valley at a level comparable to wealthier and whiter neighborhoods north of the Ship Canal is also terrible and unjust. These are not equal issues. A community continuing to exist is a vastly bigger issue than a bike lane. But both issues are real.

I certainly don’t have the answer for how to link the fight against displacement to the movement for safer streets and bike transportation, but I know we need both. People who see bike lanes as signs of gentrification are not wrong. People who see bike lanes as a way to improve traffic safety and help more people access to healthy and affordable transportation are also not wrong. And I know many people are already involved in both efforts. Because the status quo is working against both causes.

Comments

7 responses to “Last day to tell SDOT Rainer Ave needs bike lanes”

The parking lanes were also expanded (from 7 to 8 feet). So not only do you get a bike lane’s worth of space just by shrinking lanes; by shrinking the parking lanes, you also get a buffer for that bike lane.

https://twitter.com/Andres4Seattle/status/903338744564006912

Remove parking on one side of the street, and there’s your other PBL. Streetmix example here:

https://twitter.com/Andres4Seattle/status/903340196774547456

This is like the Huger Games – “Remember who the real enemy is”. They try to pit Transit vs. Bikes, but the real enemy is parking.

The survey is so leading, not only in the way they pit transit vs bikes, but also in the way they ask “Are you Sure you still want option 2” several times throughout the survey. I suspect the designs are already decided, much the way the Lander bridge was pre-decided. The survey is the city going through the motions of public outreach.

hard to have much hope that the city will pick bike lanes, seems like a cruel joke. my comment to the city was where are bike riders in alternative 1? Some people will bike on Rainier even if there are no bike lanes and those people will use the bus lane, will the bus lane be signed “bikes ok” . If the bike lanes do get built, it could be a great demonstration of what is possible, especially by removing the center turn lane for most of the way. It seems that if safety is the main goal than alternative 2 will make the safest street but at the cost of slowing down traffic and buses

Does anyone remember old Ballard? Well, it’s still not that different in terms of retail parking. While parking is tight on Market, just behind the buildings on 47th is parking lot after parking lot.

What would happen if an incentive were applied to Rainier businesses to provide parking behind buildings? Then take some of the parking on Rainier and turn it into bus *and* bike lanes.

Or is this a backward idea: providing more parking? Long term, I think so, but as a 10-20 year solution, I think it’s ok.

I am very skeptical that SDOT and city will do the right thing for bikes in RV. It never has.

And the survey seems to be set up to rally everyone who doesn’t ride a bike, to find fault w #2. ‘option 2 will slow traffic, buses, increase crime and ruin your life, are you sure you want Option 2’?

Ultimately, this will be up to the new mayor. I give bike lanes on Rainier a 30% chance.

Tom,

The north part of Rainier Avenue South has no parallel parking. How can SDOT provide both bus stops at the curb and protected bike lanes at the curb? Martin Duke is correct; they both cannot fit. In the southern stretches, they are adding parallel parking; as with Dexter Avenue North, the parking can be in the same lane space as bus islands. But as you write, is parking really a high enough priority for the limited street space. Of course not. Perhaps the bike facility has to be on a second street. Both bike and transit have the desire due to grade to be on Rainier Avenue South. All ages facilities could be placed elsewhere; transit and road warrior cyclists could continue on Rainier Avenue South.