Seattle has a Bicycle Master Plan, a Pedestrian Master Plan, a Transit Master Plan and a Freight Master Plan. It’s well past time our city give the same treatment to the many people who drive cars in our city by creating the first ever Seattle Car Master Plan.

I am only sort of joking.

Without a Car Master Plan, many of Seattle’s biggest transportation investments are being spent without a clear focus on how these public projects will help us reach our major climate change, race and social justice, public health, housing growth, and high-level transportation goals. All of the other modal master plans take these issues seriously, but those master plan projects are the exception to the rule at SDOT. The default mode of operation is that every inch of road space should go to cars unless an existing master plan says otherwise. And even then, those plans are only considered suggestions that can be ignored.

But more road space is not better for people in cars, either, though it sure seems like the mayor and SDOT’s leadership has forgotten that. Building a safe bike lane on a street increases safety for all road users, including people in cars. It’s not a zero-sum game. We are all in this together, and we all need to get where we’re going safely.

Like the other modal plans, the Car Master Plan could study best practices for designing roads to reduce injuries and deaths for people inside and outside of cars and make recommendations for how to most safely keep cars moving on our streets. After all, getting to your destination without injuring yourself or others is undeniably the most important priority of a car trip.

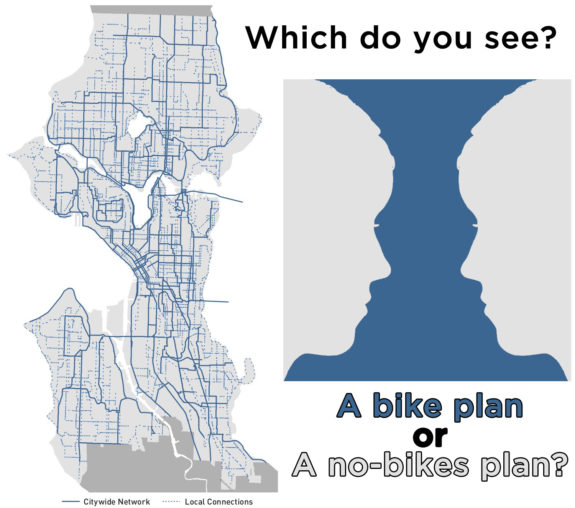

Some see a bike plan, others see a no-bikes plan

One big problem with having modal plans is that, depending on how the mayor or project team chooses to look at it, a master plan can either be a list of priority projects or a map of places where the safety and access needs of people biking can be ignored. After years of outreach and study, the Bicycle Master Plan includes a map of priority projects to be completed over 20 years. But project teams often cite the lack of a mention in the bike plan as justification for choosing not to make their street safer for biking.

The gray areas in the map above simply default to cars. They are reading the bike plan in the inverse, which is not how it was intended to be used. N/NE 50th Street, 25th Ave NE, and 24th Ave E are a few examples in design or construction right now that treat the plan this way. People bike on each of these streets all the time, and their safety matters even if they didn’t get a blue line.

SDOT folks like to say, “not all streets can handle all modes,” but it’s funny how that never seems to apply to cars. Which streets can go car-free? I’d like to see that map.

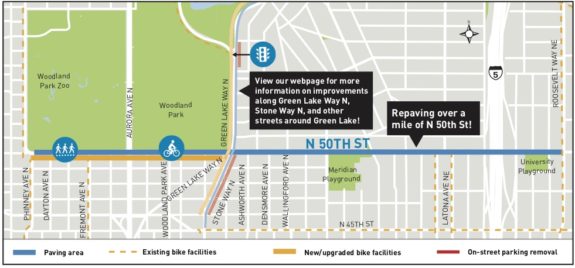

A case study: Repaving N 50th Street

Let’s take the street I used as the cover image for this imaginary document: N/NE 50th Street in Fremont, Wallingford and the U District. There is nothing unusual about this project, as streets like this exist in every part of the city (though the most dangerous ones tend to be located in less wealthy and less white neighborhoods). You can replace all references to “N/NE 50th St” with the four-lane street near your house.

This street is currently slated for a massive public investment as the city prepares to repave 1.7 miles of the street from Phinney Ave N to Roosevelt Way. There is no transit service on this street, and only the westernmost blocks have bike lanes. The street is very difficult and dangerous to cross on foot because it is four lanes for most of its length. The project will improve curb ramps and repair some sidewalks, as is legally required, but it will do little or nothing to help people cross traffic safely.

Why is this project happening, and why does it disregard safety in its basic road design? You can see how misguided the project team is by this section of the project Q&A (PDF):

Q: Can you widen the street to make room for additional improvements for all modes of travel?

A: Unfortunately, we are not able to widen the street to make room for additional improvements because in most cases we’d need to acquire property … As a result, we are designing the streets to be built within the existing curbs.

Q: Will the project eliminate travel lanes?

A: The current project design will not eliminate general travel lanes…

Did you see what happened there? The project team is saying, “We are going to continue giving all the road space to cars. And if you are asking for help crossing the street or getting around safely by bike then you must be asking us to buy and demolish people’s front yards, which is a very unreasonable request to make.” This is the bizarre response of a team that has lost its way and needs guidance. Nobody is asking them to buy people’s front yards, and they know it. People want to be able to walk and bike across and along this street in safety.

This response also points to the need for a Car Master Plan. Because any effort to get a safe crosswalk or bike lane or bus lane requires massive study and advocacy work to prove both its viability, need and public support. But extra general purpose lanes never need to go through such a process. How does the inclusion of double-barrel travel lanes help the city meets its larger goals? Will it decrease greenhouse gas emissions or help more trips shift to walking, biking and transit? Will it help the city grow equitably? Will it protect the health and safety of the people using it?

Why didn’t this project ever need to answer these questions?

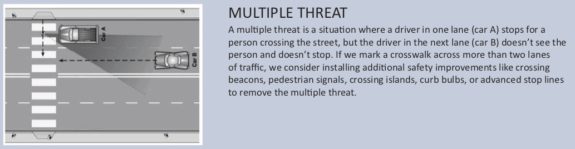

Design study: Double-barrel travel lanes

N/NE 50th Street is four lanes for most of its length, and at most points there are multiple through lanes in the same direction. I refer to these as “double-barrel travel lanes” because they create a well-known and studied traffic danger called a “multiple threat.” You may not have heard that term before, but you have experienced it. And it affects anyone trying to cross or turn left across two lanes traveling in the same direction, whether you are on foot, bike or in a car. It goes like this: You want to cross, and someone in lane closest to you stops to let you go. But you can’t see around that stopped car, and neither can the person driving in the next lane over. So you step or bike or drive out just as *BOOM*, someone comes barreling through at cruising speed completely oblivious to your existence.

This scenario is the cause of very serious collisions types, including t-bone car crashes, which are among the most dangerous and deadly types of car crashes (only head-on crashes are worse). Even a street designed solely with the safety of people in cars in mind would eliminate this scenario. And the good news is that we know how to do so: Build one through lane per direction. The space freed up can be used to build bike lanes or safer crosswalks or turn lanes or space for planting trees or stormwater-cleaning bioswales or car parking or loading zones or whatever the street needs.

There is no legitimate justification for double-barrel travel lanes on a city street, yet Seattle has no process through which the building of these dangerous lanes are forced to prove their value, viability and alignment with our other city goals. And it’s time for that to change.

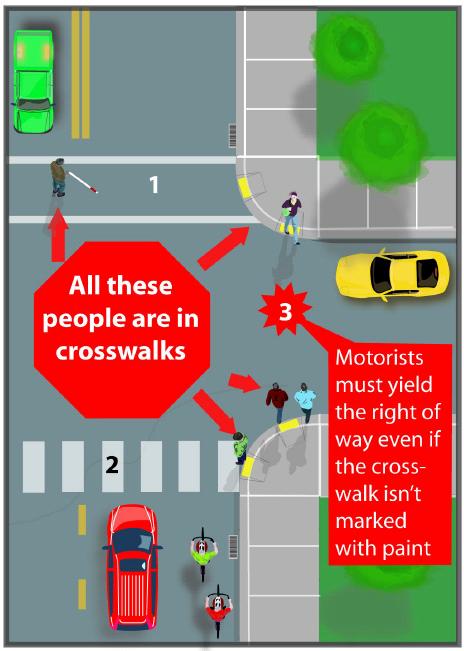

People walking should be the default mode

Right now, SDOT’s default transportation mode is driving. This is wrong, as I’m sure a Car Master Plan would note. Legally speaking, people walking have the default right of way, and our streets should reflect this. Did you know that nearly every intersection is a legal crosswalk whether it is painted as one or not? If you step off a corner into a four-lane street, for example, everyone driving is legally required to stop for you. But they won’t, and that’s due to the street design.

When repaving a street, SDOT should be required to design every single legal crosswalk to be safe to use. Or to put it another way, a person walking should always be able to cross the street. It is SDOT’s job to make sure their street design encourages legally-required yielding, and a great side-effect would be that many more trips in the area would become more viable by foot or other assistive mobility device because people would not need to walk blocks out of the way just to get to a safe crosswalk.

All crosswalks should be legally required to achieve some high compliance threshold (preferably 100 percent, though there are always a few jerks who just don’t care). But SDOT continues to design streets with legal crosswalks they know will not be respected by people driving. This is unethical, and it’s clear that nothing short of a change in law will shift the department’s anti-walking priorities.

The same goes for the use of beg buttons that are used as a way to skip walk signals entirely when nobody pushed the button in time. This results in dangerous situations where people realize too late that they are getting skipped and make a run for it. There are also walk signals where people are expected to wait far longer than is reasonable. There should be reasonable limits on how much time is allowed between walk phases.

And all this would fit perfectly in a Car Master Plan, because it is clearly in the best interest of people driving that they don’t hit somebody trying to cross an unsafe street.

Wow. This is powerful. Ghost traffic carnage. People are dying on our streets so in all kinds of ways. These collisions are preventable, we just need to stop being numb to it. https://t.co/OmnLCDzaiI

— Seattle Bike Blog (@seabikeblog) April 26, 2019

Vision Zero and complete streets with teeth

OK, this post have been mostly in jest because every point I have made about why we need a Car Master Plan has already been codified elsewhere, most explicitly in the city’s Vision Zero plan and complete streets ordinance. But these documents are not being seriously followed, and that needs to change. Perhaps it’s time for the City Council to pass a complete streets ordinance that actually has teeth. We need a law that requires the city to make streets safer for all road users, not one that merely forces the city to “consider” their needs. Because someone who is injured while crossing double-barrel travel lanes is not helped by the project team’s consideration.

Perhaps we also need to specifically identify dangerous road conditions that SDOT must eliminate when conducting road work, including double-barrel travel lanes, extra-wide travel lanes, slip lanes for fast turning and beg buttons that require a push to activate the walk signal. Because the department continues to ignore these safety issues unless projects are specifically safety projects, likely from a modal master plan.

Cambridge recently passed a law that essentially requires the city to build protected bike lanes that are in their bike plan when repaving those streets. Seattle could consider that, as well. And, as we’ve noted before, this would also help people driving because bike lanes aren’t actually for people biking, they are for people driving. Infrastructure that helps people driving avoid breaking the law or injuring other people is good for people driving.

That’s why eliminating bike lanes and cutting the bike plan is bad for people driving, too. Because the bike plan isn’t just for people who bike, it is a vision document for our city’s future. It is for everyone, even if they don’t bike themselves.

Comments

24 responses to “Seattle needs a Car Master Plan”

And the proposed bike lane on 50th was one of the ones that mysteriously disappeared from the BMP implementation from the 2017 to 2019 version, as originally reported by Erica C. Barnett. Not even mentioned in the recent list of projects abandoned.

The problem with 50th Street is that during the evening commute, it needs all four lanes. Without two lanes westbound, traffic would back up from Greenlake Way to at least Sunnyside (as it does on weekends, when there is parking on the north side of the street) and possibly past Latona to I-5. With only one eastbound lane, the middle lane is required to keep left turns from shutting down that lane. 50th Street is at capacity enough of the time, and there really is no alternative, so it’s hard to see how any additional traffic would fit.

At some point, we need to accept traffic backups as a worthwhile trade off for protecting people’s safety and making progress on our biking, walking and transit goals. Traffic backups are no fun, but traffic injuries and deaths are worse.

The existence of traffic should no longer be considered a “need” for lanes. People will stop driving if traffic backs up too far, which is exactly what the world needs to slow climate change. We should plan to rededicate 20% of car right of way to other modes, and hold SDOT accountable. I’m convinced this is the only way we will actually reduce VMT, and therefore carbon emissions and other pollutants in the city.

The data doesn’t back that up. If you look at SDOT’s 2018 Traffic Report, it includes 2017 traffic volumes. The traffic volumes for 50th range from around 20,000 average vehicles per weekday east of I-5, to just under 25,000 west of Latona. 4-to-3 lane road diets are recommended for streets under 25,000 vehicles, with different recommendations and traffic modeling being done depending upon how many vehicles the segment has. West of Latona, 50th already has only 1 eastbound lane (thanks to the other one having been converted to a center turn lane), so it’s not really that much of a stretch to consider dropping a westbound lane. East of I-5, where it’s only 20,000 vehicles, that’s a no-brainer for dropping to 3 lanes. The trickiest part (both in terms of managing vehicle flow and coordinating with WSDOT) would be the section between Latona and I-5, but even if that were left at 4-5 lanes while we made the other sections safer, that would still be MASSIVE improvement in safety.

Tame those two sections as part of the repaving project. Give it a year or so to allow drivers to adjust to the new configuration, tweak traffic signal timing and other things to ensure everything keeps moving, and then figure out how to make that last 500 feet safe for people to bike on. The coordination with WSDOT around the highway ramps would probably blow up the paving schedule anyways.

https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/SDOT/About/DocumentLibrary/Reports/2018_Traffic_Report.pdf

Also, as far as backups around Green Lake Way – that’s an argument for fixing that intersection, rather than keeping NE 50th deadly. Unfortunately, the repaving project doesn’t appear to repave that intersection, but it’s something that should be fixed either way.

What really needs to be done is to close Green Lake Way, allowing 50th and Stone to turn into a normal intersection. Fewer signal phases means less waiting for everybody, including pedestrians, bikes, and cars, which, in turn, means less backup.

In it’s place, Green Lake Way can be converted into a linear park.

This will also solve the problem that between Stone Way and Aurora, Green Lake Way is a dangerous street, and there is no safe place to cross it.

Yes! This is all-time favorite fix for Green Lake Way. Restore the neighborhood street grid, then use the big new publicly-owned parcels into a mix of affordable housing and green space (possibly selling some parcels to help pay for the whole project)

The reason for the flow rate west of Latona is because of the capacity, not the demand. Except for 10 hours a week, 50th is already one lane in each direction. During the afternoon commute, traffic is limited by capacity (2 lanes westbound), not demand. There is already spillover onto residential streets from people who would turn North at Greenlake Way. I would always drive slowly when I did that (and still save time), but it only takes a few fast drivers to create an even greater safety problem. (My experience commuting on 50th is from before Seattle added 100,000 residents; I can only assume the demand has increased.) There is also the issue of lost parking for the residents on 50th; there seems to be a fair number of parked cars in the evenings and weekends. The real problem is the limited east-west road capacity south of 85th St, because of Greenlake and the limited crossing points of Aurora. There is no alternative route that isn’t already at capacity.

1. We have seen over and over that road diets do not have a detrimental effect on car traffic. Most of the time it actually improves car traffic flow. But we still have the same tired arguments every time a street is proposed to be redesigned to be safer for all users.

2. Even if that wasnt the case: who cares. It should be painful to drive in a real city. Cars should be dead last on transportation priorities, not overwhelming first as it is now. Population density reaches a certain point and there just isnt any room for everyone to have their own personal shitbox to get around in. Its not a war on cars. Its that you live in a city. Deal with it. This is what the mayor and SDOT need to be saying in 2019. Not deferring to a vocal minority that refuse to get out of their cars.

The UN has been promoting a strategy of sustainable development which is development that is economically, socially, and environmentally sustainable. Promoting individual motorized transportation over all other modes is not sustainable. All public expenditures have to be justified by the measure of sustainability. To be sustainable, individual motorized transportation (IMT) has to be the last priority. Walking, public transport, and non-motorized transportation have to be prioritized over IMT. Politicians, urban planners, and all residents have to understand the principles. Here is a good example from Sweden: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=udSjBbGwJEg

[…] Car Master Plan: Seattle Bike Blog makes a masterful argument that other modal plans are largely ignored in Seattle and that its due time that a Car Master Plan be created to address safety for drivers and…. […]

Well put. It’s time to work on a better world, and the default mode of prioritizing cars over everything else needs to go. We really *should* have a car master plan: delineating some roads where car travel is important and making everything else by default be transit/pedestrian/bikes oriented.

Here in Kent and Auburn we have crosswalk beg buttons that loudly proclaim “cars may not stop.” Someone is prioritizing warning cyclists and pedestrians that people moving in several tons of metal may decide to kill them despite the light, rather than coming up with a solution where they don’t. Lovely public policy.

Seems straightforward: codify the principles for safe and inclusive streets from Bike/Transit/Ped plans as the city’s default transportation legislation, and write a Car Master plan that enumerates some projects that may provide for car infrastructure in the future, but fund it at a fraction of the cost of implementing it, spend part of it on other modes, and ignore it when there is push-back against particular car projects. No joke. Thanks to the principal of induced demand, this should result in safer and more pleasant streets for all, even cars.

I’ve lived about 500 feet from that photo of 50th for 15 years and I have some observations. Nobody in their right mind would ride on that street now, and even on the sidewalk you are 1-2 feet from big rigs blasting toward the freeway at 40 MPH near where the photo was taken. As I understand it 50th used to be a 2 lane road with parking strips between the sidewalk and the road, but it was widened with the removal of the parking strips that put the sidewalk right next to the road. This road wasn’t even originally designed for this volume, it was hacked. When they put in the center turn lane I was relieved as I live on Thackeray and the only way to get home from the west is to take a left, blocking the left lane in the process. The center turn lane would fix this right? Nope, when I found out the center turn lane would cease before it got to Thackeray I was deflated. Also, people eastbound on 50th making a left on Latona are in the same boat. If I had my way I would extend the center turn lane to the freeway and call it a day. This has nothing to do with bikes, but I don’t ever see this as a cycling street, 45th has more potential. I live so close to the U-district but I NEVER ride there because of the unsafe to cyclists situation on 45th and 50th. What ever happened to the idea of putting in a ped/cycle bridge at 47th?

The whole biking situation crossing I-5 in that area is completely nuts. It’s a big missing connection. My story is similar to yours. I lived in the U District for a few years, and I basically never went over to the Wallingford side for this reason.

The MOve Seattle Levy had an explicit promise to address the pedestrian and bike connection across I-5 before the opening of U Dsitrict Station. We shall see if SDOT actually delivers. I certainly didn’t see this in the BMP implementation plan.

First of all thank you Tom for this well-written post. As you say, a car master plan (CMP) is needed simply for the fact that all modes of transportation should undergo the same level of analysis and rigor when taxpayer monies are spent on them. An end goal would be a Transportation Master Plan that looks at all modes holistically, but even just a CMP would be a leap forward in leveling the playing field.

Also, your suggestion of framing transportation equity as a benefit for drivers is a great way to appeal to their self-interest. But, like you also state, you either need legislation or a public entity with some legal “teeth” to compel SDOT to look at our common right of way and transportation through it in a holistic way.

Years ago I worked on the redesign of a 51 mile stretch of highway where 42 wildlife crossings were being added as part of an overall agreement between the FHWA, two Native American tribal governments and the state DOT. Most of the users and residents only saw the benefits of wildlife crossings in that they created a safer driving environment by reducing animal/car collisions or collisions that occurred when someone swerved to avoid wildlife. There is the self-interest part.

We were hired to help represent the tribal governments on the design team specifically because they wanted to incorporate values into the design that went beyond the typical values used in highway design that focus almost exclusively on vehicle throughput. Instead of a road that divides landscapes, is a barrier to wildlife corridors and splits rural communities, we developed the concept of “a road that heals,” with the goal of using the redesign to reduce, mitigate and even eliminate many of the problems the original design created. FHWA would not fund the project unless the state DOT came to an agreement with the tribes on the design guidelines and recommendations for the highway redesign as it passed through their lands. So the tribes had the interest and legal standing to get their values included into the design process.

The irony of the project is that many of the highway engineers on the consultant team and in the state DOT pushed back against this and much of the rest of our design direction to make a “road that heals.” Once the project was completed and is now celebrated as “The People’s Way” they were quick to claim credit for holistic design they pushed so hard against implementing. It is now held up as a model for highway redesign.

I plan on sending this blog post to the mayors office and to SDOT and urge others to do the same. With the 35th AV NE fiasco and the car centric improvements to Sand Point Way currently under design, I hope this post gives the current city administration some much-needed perspective and vision as they implement improvements that we will have to live with for the next 25 years.

It’s not easy but it can be done.

Great writing!

Some other street designs that should be outright banned:

1) Double right-turn lanes, which force cyclists to lane-change left in heavy traffic in order to continue straight. (https://goo.gl/maps/nV1EkRJSZFCtpBMUA)

2) Traffic signals with a crosswalk on only one side of the street (https://goo.gl/maps/e61e3daBnv72hScq5)

3) “Don’t walk; use crosswalk =>” signs (https://goo.gl/maps/e61e3daBnv72hScq5). If there’s enough people that want to cross the street to justify putting in the “don’t cross” sign, just put in a crosswalk, instead.

4) Traffic signals that allow only cars to cross the street, not pedestrians: https://goo.gl/maps/iCQjWVcss6m55jYS8

5) Unnecessarily wide turns encouraging people to go around the corner to fast: https://goo.gl/maps/89xqMQZwmCjXFKmV7

SDOT can’t publish a car master plan because it wants to ban cars as much as you do. It creates gridlock on purpose.

You’re not getting those bike lanes because SDOT and FAS mismanage the design process, staffing, and contracting. And breaks state and federal rules that drag out or lead to cancelled projects.

What you should be asking for is an independent procurement, financial, and resources audit not done by the politically compromised, under paid, under specialized and high-turnover State Auditors Office. SDOT is beyond the pail when it comes to wrongdoing and bad intentions.

The idea that SDOT is working to abolish cars is the big myth out there. SDOT operates within often unspoken constraints that need to be made clear: the truth is that every transit project, every bike project, every pedestrian project first and foremost needs to pass a bar of minimizing impacts or improving traffic operations and, to a slightly lesser extent, the same can be said for on-street parking.

Traffic modelling and bending over backwards to make every multi-modal project a win-win for traffic operations is a huge drain on the “bike project” budgets, “transit project” budgets and the “pedestrian project” budgets even though these efforts are primarily geared toward benefiting cars. To make matters worse, outrageous outreach budgets like what we saw play out on NE 35th hit the “bike” budget despite no bike infrastructure ever seeing the light of day.

I love that Tom focused on 50th because that is the type of road we should be having debates about. Instead, 50th is basically off limits for any safety improvements. Meanwhile, Sand Point Way’s “vision zero” project appears to be backtracking on the original concept to put in a road diet between NE 65th and NE 77th, despite the fact that there are only 16,000 cars per day. In that situation, the corridor concept study even showed that a road diet would improve operations, but evidently the safer, better design for traffic operations hurt some drivers feelings, I guess.

As Tom rightly points out, the default on all arterial streets is to allow the heaviest traffic flow and fastest vehicle speeds possible. If we are going to say that traffic capacity on 50th is more important than safety, at a bare minimum SDOT needs to say so explicitly so our city is making informed decisions. Right now this decision is made by default without any public scrutiny and somehow the myth that SDOT is working to abolish cars persists.

FFS, we need a Transportation Master Plan. Cars, Bikes, Pedestrians, Transit, Freight. It all needs to work together.

Without a plan stating what the goal is to direct them in a certain direction, the status quo will continue to prevail.

Getting them to state out in the open what they’re about and what their goals are would probably expose their true intentions or they’d lie and pay lip service and then continue on normally but then you could catch them on it.

What’s needed is political change. Next election, ask each candidate how they would vote on specific motions. Check their track record in their careers to see if it’s likely they would stick to it.