Transit is getting cut. But Seattle voters will have the chance in November to make the cuts less awful by approving the Seattle Transportation Benefit District’s (“STBD”) sales tax measure.

As we reported previously, state legislators and the court-pending voter approval of 2019’s I-976 have put the city in a very tough spot. Seattle voters approved the STBD by a wide margin in 2014, improving transit frequency and investing in transit access programs like the ORCA Opportunity Program to provide free transit to public school students. The 2014 measure expires at the end of the year and included a 0.01% sales tax and a $60 vehicle license fee, but the license fee portion is now wrapped up in the courts after Washington voters approved I-976. That initiative would have limited license fees to $30, though Seattle, King County and others are challenging its constitutionality.

But with the court case still ongoing, putting a new car tab measure on the ballot was not a significant part of the discussion for the 2020 measure. And because the state legislature did not provide transportation benefit districts with any new revenue options, Seattle is forced to go to the ballot with a regressive sales tax.

But while sales tax is regressive, hitting low-income folks the hardest because they don’t have the luxury of saving their money, cutting transit is also regressive, taking time and mobility away from people who rely on transit to get around.

The initial proposal from Mayor Jenny Durkan and City Council Transportation Chair Alex Pedersen would have only renewed the 0.1% sales tax, effectively cutting the measure in half or worse depending on the economic fallout from the pandemic. The 2014 measure had been bringing in about $56 million per year. The Durkan/Pedersen version would have brought in $20-$30 million per year.

Councilmember Tammy Morales championed the idea that the city should max out its funding capability allowed under state law and proposed a 0.2% sales tax. This would have gotten close to maintaining current funding levels, though of course at the cost of furthering our reliance on sales tax. Her amendment barely failed with Councilmembers Kshama Sawant, Teresa Mosqueda and Dan Strauss joining Morales in a 5-4 defeat.

Instead, Council President Lorena González proposed a halfway compromise of a 0.15% sales tax, and that effort passed 8-1 with only Councilmember Pedersen opposed. So this is the version that will go to voters. If approved, the measure would bring in an estimated $39 million per year, the Urbanist reported. Still a significant cut, but not as bad as the original proposal.

Though an extra 0.1% sales tax is not a huge amount of money for many people (if you spend $30,000 in a year in Seattle on taxable items, that’s an extra $30 in taxes), the idea of raising taxes at all when local businesses are closing or barely hanging on is a tough sell. And we have among the most regressive tax structures in the country, with low-income people paying a far higher share of taxes than wealthy people because Washington does not have a state income tax or many other more progressive tax methods. So tacking on even a little more sales tax is a step in the wrong direction from the perspective of fair taxation.

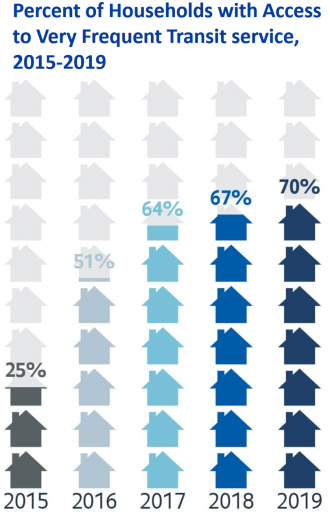

However, cutting transit funding when it is facing its biggest challenge in a generation due to decimated ridership during the outbreak is also a terrible idea. Before the outbreak, transit ridership was growing very strongly in Seattle, and it wasn’t just because of light rail. The frequent bus network funded in large part by the 2014 STBD has been the unsung hero of the past half decade, and it’s a major reason why Seattle transit use grew while transit use in most other cities fell or stagnated. In other words, it was working.

The proposed measure would prevent some of the worst transit cuts within Seattle’s city limits, cuts that would be terrible for people who rely on transit, terrible for businesses, terrible for traffic and terrible for our climate change goals. But we need the state to step up and authorize more revenue options for local and regional transit funding measures. We have huge ongoing needs for funding walking, biking and transit projects and services that we need to meet if we are ever going to serve our city and our region’s growing population and our equity, safety and climate change goals. The measure going to voters in November will be good for six years (an effort to reduce it to four years was narrowly defeated), but we shouldn’t wait that long to revamp how we fund transit. We need a regional solution that is also progressive and stable. We can’t keep finding ourselves in a situation where we need to desperately try to save the bus network every six years.