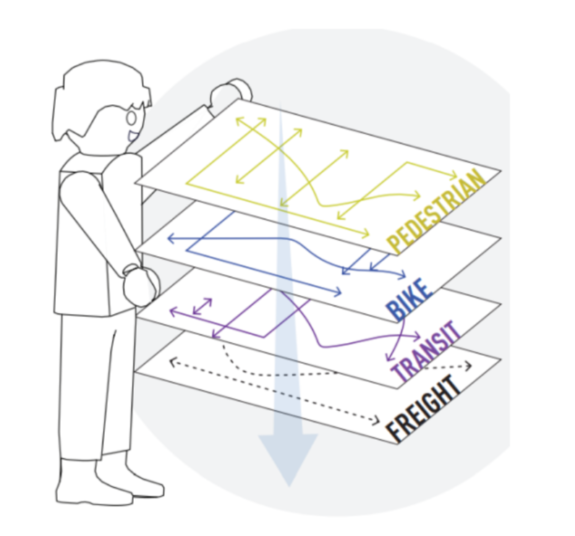

In late 2020 and early 2021, the Seattle Bike Blog covered work happening behind the scenes at the Seattle Department of Transportation to work toward integrating the city’s different modal plans (bicycle, pedestrian, freight, transit) into one plan. This technical work will underpin the Seattle Transportation Plan, which the department formally started public outreach on last week. All of this work will ultimately be incorporated into Seattle’s major update to its Comprehensive Plan, to be finalized in 2024.

Details of that technical work revealed how SDOT was developing a map of “critical” bike corridor segments across the city; segments that the department didn’t deem critical wouldn’t be prioritized for added bicycle infrastructure in cases where the street width was found to be too narrow. An analysis of every block in the city compared against the various modal plans found that it was just the facilities outlined in the 2014 Bicycle Master Plan- 339 out of 340 blocks citywide- that were found to be creating conflict between the existing modal plans.

Only prioritizing protected bike lanes where they’re deemed critical is an easy way to resolve the conflicts, but the point of a citywide network is that it’s citywide. It also sidesteps the fact that installing bike facilities where they’re called for in the BMP is about making people using those routes safer. SDOT is already contemplating a freight lane policy that could mean some bike riders who feel comfortable using transit-only lanes would need to find somewhere else to be. But not prioritizing people on bikes on a specific street doesn’t mean they go away, it likely just means it’s more dangerous for them to be there. This work looked to mean the end of the bicycle master plan as we know it.

A draft map of these critical bike segments was due to be released by this month, but has been delayed by SDOT. Now new internal documents requested by Seattle Neighborhood Greenways and reviewed by us illustrate how concerns from other departments within SDOT have been raised around how safety is incorporated into the modal prioritization framework.

In a document dated mid-November summarizing how this work could impact SDOT’s Product Development Department, those concerns are noted. “Staff are concerned that with the implementation of [the Policy and Planning Department’s] Critical Bike Network…that this will change how the [Bicycle Master Plan] is implemented,” the document reads. “Additionally, staff are concerned this policy with [sic] deprioritize safety for vulnerable roadway users.” Seeing concerns raised in writing like this is pretty notable, and those concerns align with alarms being raised by those outside the department.

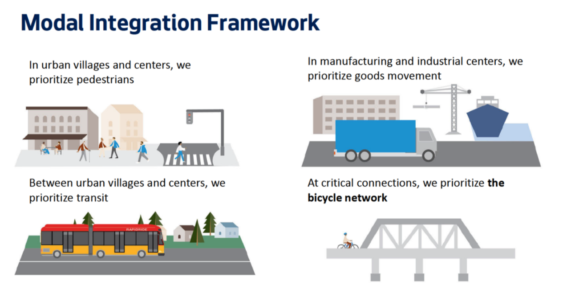

Copies of presentations that were set to be given to the Bicycle Advisory Board—but which have been postponed—show how the primary criteria for identifying critical connections include network integrity (spacing separated bike routes no more than 1/2 mile throughout the city) and network legibility (fewest number of turns on flattest route). These criteria have a lot to do with safety, but they aren’t themselves concerned with keeping everyone on bike routes designated in the current Bicycle Master Plan safe.

“The Seattle Transportation Plan updates and combines the city’s bike, pedestrian, transit, and freight master plans into one plan. It determines how and where each of these modes can fit into Seattle’s streets,” an action alert released by Seattle Neighborhood Greenways this past Saturday noted. “So far, planning for bike routes doesn’t include safety, equity, and connectivity filters. That’s a big problem.” SNG is asking people concerned about this issue to contact the city council. Cascade Bicycle Club is doing the same, pushing for the new plan to build on the work that shaped the BMP and not to start over.

Concerns raised around the policy were enough to prompt the city council to adopt a proviso in last year’s budget requiring that work be run by the council. Tomorrow morning’s Transportation & Seattle Public Utilities Committee meeting will be one of those chances as SDOT presents on the Seattle Transportation Plan. The councilmember who proposed the proviso, M. Lorena González, is no longer in office, but this plan will need close attention from at least one councilmember if it’s to be improved.

The Seattle Transportation Plan starts from a solid foundation of seeking to integrate the modal plans, and SDOT’s plans for public outreach all look better than anything the department has ever done, but if the technical work that makes up the core of the plan is flawed and doesn’t center the safety considerations that lie at the heart of the current Bicycle Master Plan, we will be assured bad outcomes when it comes to making space for people on bikes. If we don’t get it right, it could set things back for a decade or more.

Comments

17 responses to “Concerns raised within SDOT about modal integration policy as advocates sound alarm”

Well, I think there are plenty of dedicated, hard working people in SDOT. But as a whole, is it a systemic problem or simply the direction given from the top ? Why does SDOT fail so miserably in so many ways.

With respect to biking,

– they make speed bumps when they fill potholes that are just as bad as the pothole

– they almost never sweep bike lanes free of debris

– they can’t design a protected bike lane without making riders zig-zag across the street

– they don’t leave enough width for lanes next to parked cars

– they design protected bike lanes for substandard speeds, some places less than 10mph

– they often don’t respond to find-it-fix-it requests, even after multiple phone calls

– they allow vegetation (blackberries) to encumber bike lanes and sidewalks

– they design bike lanes without drainage so that there are bathtub sized puddles

– they allow gravel and rotting leaves to accumulate in bike lanes, making it slippery

– they ignore cracks between sections of concrete that create railroad track-like grooves

I realize funding can be an issue. First, however, they need to care. I don’t see that.

The design issues brought up in this article are just one manifestation of this incompetence. It’s a big-picture problem.

I agree with those criticisms of SDOTs treatment of bike infrastructure – they are spot-on. But I also think it does come back to the point made at the top: is this ingrained in SDOT as an institution or a result of poor leadership? I’d add in a reflection of the general misguided societal attitude that bikes aren’t really ‘transportation’ so we shouldn’t invest in cycling infrastructure or that it should be the lowest priority.

Thanks for your comment. Aside from some loudmouthed pundits, how many people *don’t* think of cycling as transportation ? Is that really a factor ? It would be useful to know.

A couple of years ago I attended a community meeting on implimenting Rapid Ride from SLU up Eastlake and into the U District. The overwhelming local sentiment was against Rapid Ride (because it would reduce/eliminate on-street parking) and against the proposed protected bike lanes (because ‘that’s not transportation, that’s Lance Armstrong wanna-bes getting their exercise’). Just first-hand aneddotal experience on my part, but I seem to hear it time and again.

An underlying reason that some are pushing to “integrate” the modal plans: To do an end run around the Complete Streets ordinance and the Bicycle Master Plan, at the expense of bike route safety and connectivity. The modal plans, especially transit, need updates, but none of them were conceived or written in isolation. This process has some opportunities for improvement and much danger of regression.

Councilmembers asked good questions at SDOT’s presentation to the Transportation Committee:

Herbold:

What happens to the annual implementation plan updates for each modal plan?

Morales:

How will the Seattle Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Analysis be used in the new plan?

How will the new plan achieve the Seattle Climate Action Plan goals for emissions?

How will the new plan work for people with disabilities, low incomes, and people displaced by Seattle but who still need to come to Seattle to work?

How will the plan avoid putting biking, walking and transit into competition for space?

Strauss:

Nice to see that one diagram now has a truck graphic instead of a car. Truck and bike coexistence is necessary for safe transportation and goods delivery. How will plan consider that?

SDOT responses were basically “blah blah blah wholistic blah blah blah outreach blah blah blah…”

Other questions that come to mind:

What will happen to the bike, pedestrian, freight and transit advisory boards?

Who will be the citizen-stewards of a new integrated plan?

> What will happen to the bike, pedestrian, freight and transit advisory boards?

So far as I can tell, the alphabet soup of advisory boards are ineffectual talking shops whose feedback is mostly ignored. I, for one, couldn’t care less what happens to them.

> Who will be the citizen-stewards of a new integrated plan?

Our elected officials, that’s their job?

Roadways have multiple purposes. The Master Bike Plan cannot be implemented without causing significant problems for pedestrians, delivery drivers, bus routes, shuttle routes, Uber/Lyft drivers and all the other roadway users. Bike riders are 3% of the roadway users and that number isn’t growing significantly. The Bike Master Plan isn’t effective or sustainable. Sorry — reality.

That type of attitude sure sounds a lot like “the beating will stop when you stop wailing.”

Most of the bike lanes proposed in the master plan make space by taking away parking, not travel lanes. So, a fair numbers comparison is not between people biking on a street vs. people driving on that street, but between people biking on a street vs. people parking on that street. Considering that other parking options exist (parking lots, side streets), the number of people that bike on the average Seattle arterial street each day well exceeds the number of drivers who park there (remember, by “there”, I literally mean “parking on the street”, not in an adjacent parking lot).

Even in cases where a travel lane is impacted (say, 125th St.), SDOT has conducted exhaustive traffic counts and concluded that the vacated travel lane is simply not needed. If a single travel lane already provides enough capacity to avoid significant delays to drivers, drivers don’t really gain anything from the second lane, except, of course, those who want to weave around everybody else and drive way over the speed limit. I don’t care what the numbers are, basic safety says you do not effectively prohibit bikes from using a street entirely, simply for the sake of allowing a small set of drivers who want to drive 50 mph in a 30 mph zone to pass people going the speed limit. I will also point out that even empty bike lanes still increase the distance between the sidewalk and motor vehicle traffic, which, in turn, makes it more comfortable to walk on the sidewalk.

I like the “parked cars vs riding bikes” numbers argument. Cars parked for commuter-parking storage on arterials is wasteful. But parking for customers is a different equation. And load zone infrastructure is the big one here. UPS, FedEx, Amazon, Uber, Lyft, Grubhub, Doordash — these are the current growth areas in urban design. I suspect private shuttle services that are more convenient than public buses are soon to explode on the scene. These all need the curb lanes on arterials. It is multi-modal ever-shifting complicated, making exclusive use arterial bike lanes difficult to justify to recreational and non-bike riders.

Customers don’t need to park on an arterial street. The have parking lots and side streets. Same with delivery vehicles.

Seattle is not picking on cyclists; it underfunds all the modes; pavement management is poor; the seven RapidRide lines that it took on are all late; the G Line is not electric trolleybus; the G Line alignment does not provide a short transfer walk with Link; the two or three local streetcars are very costly, unreliable, and poorly planned and executed (they should not be); sidewalks are lacking and poorly maintained. It is very difficult to implement all ages bike facilities on transit arterials; note that the projects on Broadway, 2nd Avenue, Pike, Pine, and NE 65th Street all slowed transit. There is not sufficient right of way to implement all the modal plans; SDOT needs to figure that out; it is about time they began to do so.

asdf2 wrote: “Most of the bike lanes proposed in the master plan make space by taking away parking, not travel lanes”. I do not know this; it may be so. Travel lanes were taken for several prominent PBL projects: NE 65th Street, Broadway, 2nd Avenue, 4th Avenue, Roosevelt Way NE, Pike and Pine between 2nd and 6th avenues. Transit was slowed as it was stuck in congested general purpose traffic. The road diets provided space for bikes incidentally; the prime benefit was pedestrian crossing safety (e.g., Nickerson, Stone Way, NE 125th Street, Phinney-Greenwood, 24th Avenue NW). They seem successful. Some remain dicey; consider 8th Avenue NW; the bike lane is between car doors and potholes. Some are intermittent. The key overlap to be addressed is attempting to provide PBL on transit arterials; it takes more capital; all modes are slower; that may be safer; but it makes transit less attractive. What is the review of Union Street and Route 2?

I’m going to need some citations here.

Travel lanes were taken from NE 65th St? Where exactly? Here is streetview from 2007: https://www.google.com/maps/@47.6758578,-122.3184206,3a,75y,89.89h,91.98t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1s66tQad5XphoPJA5wftJ69A!2e0!7i3328!8i1664

Roosevelt Way NE was mostly off peak parking. Streetview from 2008: https://www.google.com/maps/@47.6715654,-122.3174153,3a,75y,6.56h,81.23t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sgJo85ezez_C45vsXDNQiFw!2e0!7i13312!8i6656

What evidence is there that buses on 65th or Roosevelt were slowed down? I haven’t experienced any issues here. In my experience, these streets work better for all road users after these improvements.

Nick: see SDOT https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/SDOT/About/DocumentLibrary/Reports/NE65thSt_Evaluation_Report_91620-1.pdf This is the after study by SDOT. See page 12 for transit travel time increases (in a very short segment). A peak period travel lane was taken from both arterials. On Roosevelt, the peak scheduled times for Route 67 are longer. On NE 65th Street, the SDOT report had AVL data. All modes are probably safer. An alternative approach would have placed the all-ages bike facility on a parallel street; cyclists comfortable in traffic may continue to use transit arterials. Note the bike facilities are not continuous; east of the study area, the bike routes shift to NE 68th Street. On NE 65th Street, the single lane has long queues behind the signal at 15th Avenue NE. The prime objective of the project was improved safety; a side effect is slower transit. The Roosevelt project was in 2016. The later SDOT manual suggests that on one-way streets, bike lanes should be on the left side opposite the bus stops.

Thanks for the info! I guess I haven’t noticed the 1-2 min difference on the 62. The opening of Roosevelt’s new light rail station has had a major impact on my transit travel times. Roosevelt to International district has gone from 60 min to 20 min for me.

Yes, Link is fabulous. It would be better if ST funded shorter headway and waits.