On his first day on the job, SDOT Director Greg Spotts pledged a “top-to-bottom review” of the department’s Vision Zero program to figure out why traffic injuries and deaths are increasing, especially for people walking and rolling. He assigned employees from outside the Vision Zero team to perform the review, and they released a draft of their findings Thursday.

On his first day on the job, SDOT Director Greg Spotts pledged a “top-to-bottom review” of the department’s Vision Zero program to figure out why traffic injuries and deaths are increasing, especially for people walking and rolling. He assigned employees from outside the Vision Zero team to perform the review, and they released a draft of their findings Thursday.

The document is mostly designed to be inside-facing, meaning it is intended to guide the department on how it can better deliver safer streets. But it also notes a few areas where the department needs outside help, mostly in the form of clear leadership and better funding for safety initiatives.

Most of the findings are probably not news to regular readers of Seattle Bike Blog, but it’s good to see them confirmed. For example, they found that when the city makes safety changes to streets, streets get safer.

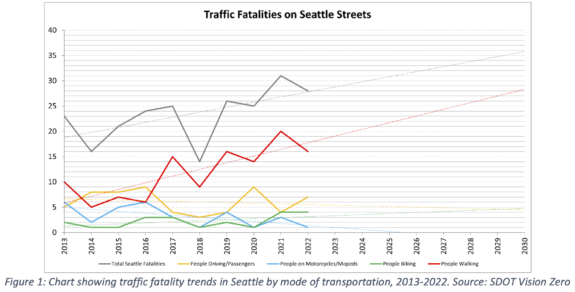

“We found that safety interventions and countermeasures used by SDOT to advance Vision Zero make our streets safer,” the report notes. In fact, the report does not in any way place the blame for Seattle’s lack of safety progress on the existing Vision Zero program team. Every time it analyzes the team’s work, it finds that they are effective. The team has produced valuable data highlighting problem areas that need safety fixes citywide, and the relatively few projects they have led have made those streets safer. The problem is that they are just a small team with a very modest budget. A few miles per year will not get us to Vision Zero any time soon, especially at a time when deaths are on the rise nationwide. One way to put it is that the national and statewide trend of increasing traffic deaths is overpowering Seattle’s Vision Zero efforts in recent years. But that’s not an excuse, it’s a call to action.

Vision Zero is supposed to be a department-wide goal, and that’s where the work often falls short. The report offers a list of strategies for doing better. “We also identified dozens of potential opportunities to improve SDOT’s Vision Zero efforts – by strengthening policies and improving policy implementation, streamlining decision-making, improving project delivery, and moving more quickly toward broader implementation of proven interventions where they are most needed.”

Vision Zero is supposed to be a department-wide goal, and that’s where the work often falls short. The report offers a list of strategies for doing better. “We also identified dozens of potential opportunities to improve SDOT’s Vision Zero efforts – by strengthening policies and improving policy implementation, streamlining decision-making, improving project delivery, and moving more quickly toward broader implementation of proven interventions where they are most needed.”

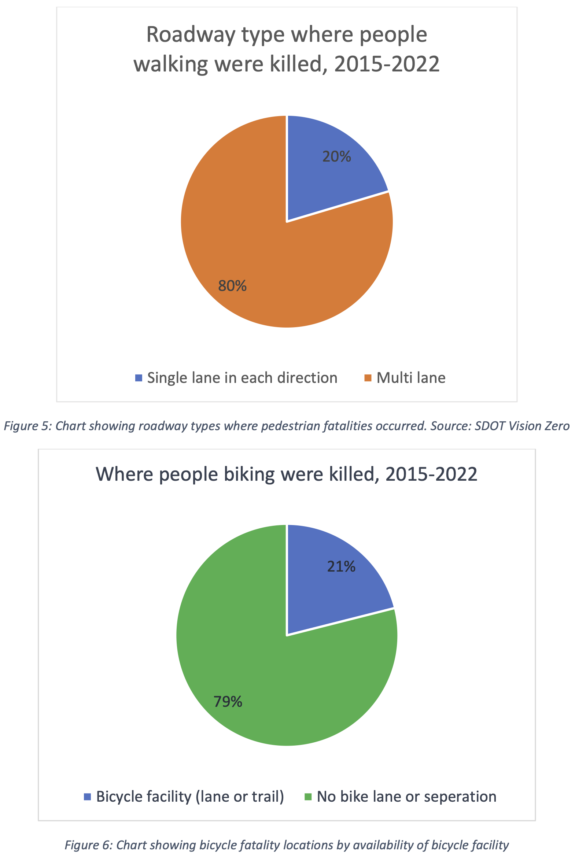

Specifically, the report found that achieving Vision Zero mostly requires safety redesigns on the city’s arterials, particularly arterials with multiple lanes in the same direction. “SDOT analysis shows 93% of pedestrian fatalities occur on arterials, and 80% of those fatalities were on arterials with more than one lane in each direction,” the report notes. “Our data also show that 80% of people killed while biking were biking where no bike facility was available.”

Specifically, the report found that achieving Vision Zero mostly requires safety redesigns on the city’s arterials, particularly arterials with multiple lanes in the same direction. “SDOT analysis shows 93% of pedestrian fatalities occur on arterials, and 80% of those fatalities were on arterials with more than one lane in each direction,” the report notes. “Our data also show that 80% of people killed while biking were biking where no bike facility was available.”

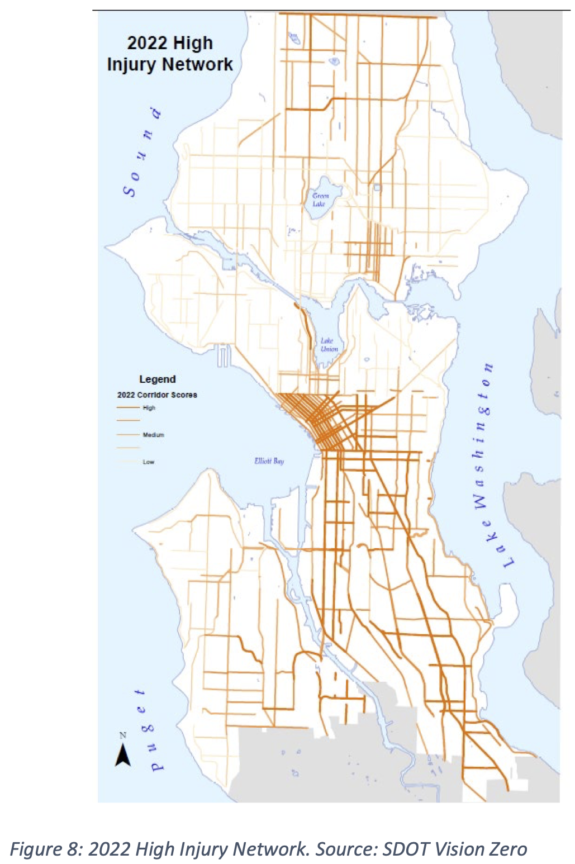

They even made a map to demonstrate the problem, which they called the “High Injury Network.” It shows “the highest number of serious injury crashes occur based on the density of total collisions and fatal and serious injury collisions.” The city then applied the city’s Race and Social Equity Index to the map to aid in prioritization:

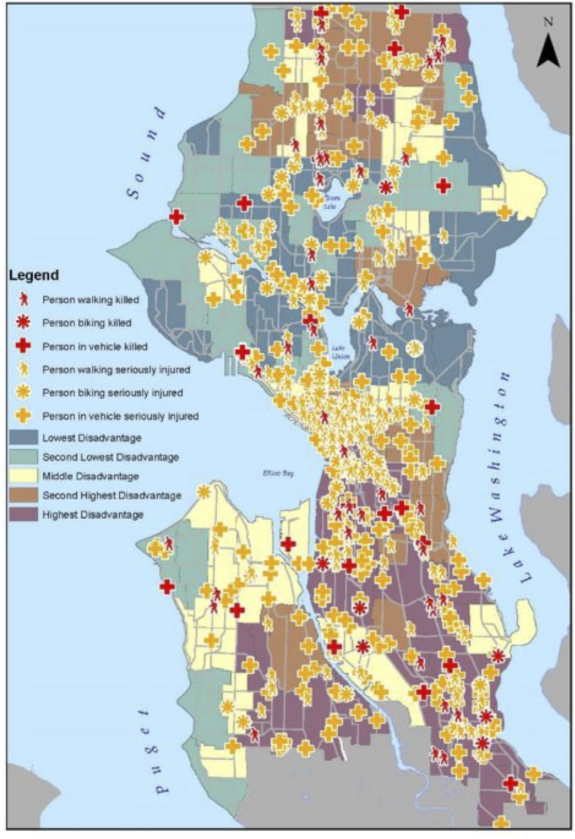

They also collected all reported serious injuries and deaths from traffic collisions into a map:

They also collected all reported serious injuries and deaths from traffic collisions into a map:

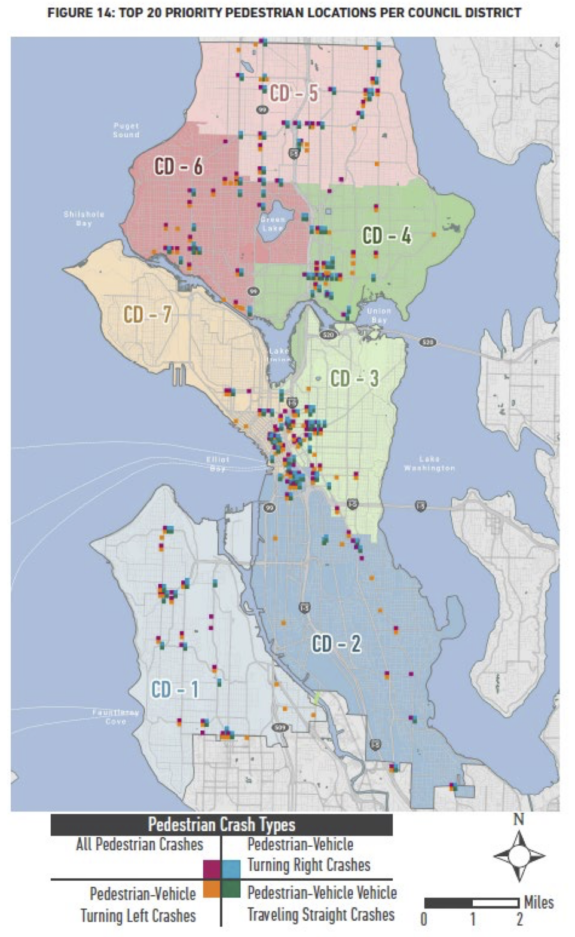

Thanks to the Vision Zero team’s anticipatory road safety analysis tool (which they call the “Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Analysis”), they are also able to identify streets and intersections that either have a high injury rate already or that have similar conditions to locations where injuries have occurred. The idea is to be able to make safety improvements before a death or injury has occurred rather than waiting for the “data” to justify such investments. Because the “data” in these cases are people. Here’s a map they generated highlighting the top 20 highest-priority locations in each Council district for pedestrian safety improvements:

So if we know how to redesign streets to make them safer and we have the data showing where safe streets interventions are needed, what’s the holdup? This is where the report gets interesting. One recommendation is quite blunt: “Be willing to reduce vehicle travel speeds and convenience to improve safety.” The report then dives deeper into the ways that the department’s existing systems resist this recommendation. The following section will likely ring true to many frustrated safe streets advocates:

“Applying existing standards on a project-by-project basis and justifying deviations can be cumbersome; updated design guidance documents could help streamline decision-making and documentation requirements in many cases. The process and authority for decision-making is also not always clear. Decision-making around improvements that improve safety and slow vehicular traffic can be especially difficult—due to competing priorities, a lack of clear direction from leadership, and other concerns—even though safer speeds are a key component of Safe Systems.”

In other words, despite existing Vision Zero and complete streets policies, SDOT’s internal systems still make it easier to simply reproduce existing dangerous conditions rather than go through the more difficult process of making safety changes. This is a big reason why after repaving many streets, the department simply repaints the lines the way they were before. It’s the path of least resistance. The internal incentives are backwards. An existing street design that we know is dangerous should not be the starting point in the design process. A safe design should the starting point, and SDOT’s internal systems should make the safe street the path of least resistance for project teams. Rather than requiring safety improvements to go through a difficult justification process, project teams should instead need to justify any deviation from proven safe designs. It should be difficult for an SDOT project team to ever stripe a street with multiple lanes in the same direction, for example, because the project team should be required to justify that decision and explain how they are going to make it work safely for all road users as part of the initial project.

But the report notes that the problem does not merely lie with the department here. They can only propose safety changes if they have “clear direction from leadership,” and that includes political leadership from the Council and especially the Mayor, who oversees the work of the SDOT Director.

In addition to recommending actions SDOT can take immediately, the review document will also be used to inform other plans in process such as the Seattle Transportation Plan. Hopefully it will also help inform the priorities of the next transportation levy, which is the city’s next big chance to direct significant local funds into safety projects.

But SDOT is not waiting for a 2024 vote to take action on the plan’s recommendations. SDOT Director Spotts and Mayor Harrell list five “momentum-building actions to implement in 2023”:

- Accelerate planning for broader or systemwide implementation of proven interventions — Specifically, they will install additional turn on red restrictions downtown.

- Accelerate planning for broader or systemwide implementation of proven interventions — They will “accelerate leading pedestrian interval rollout,” giving the walk signal a head start before people driving get a green light.

- Be champions for Vision Zero as we engage with our partner — Specifically, they say they will worth with Sound Transit to improve safety along the light rail on MLK.

- Expand automated enforcement in a data– driven equitable way

- Strengthen SDOT’s Vision Zero core and matrix teams — The City Traffic Engineer will now be a Chief Safety Officer

You can read more in the Overview and Full Report documents.

In all, there is good stuff in this report. But the recommended actions don’t seem to rise to the level of response we are going to need to actually achieve major reductions in traffic injuries and deaths. Look again at the first chart in this post. This is an emergency. I was hoping for more specifics. For example, the report notes that 80% of fatalities occur on arterial streets with multiple lanes in the same direction, but it doesn’t specify actions that seem commensurate with the scale of that danger. It recommends that the department should “evaluate multi-lane arterials where most pedestrian fatalities occur” and that they should “identify and plan for opportunities for lane reductions while maintaining transit and freight networks and emergency response capabilities and being transparent about expected impacts to general purpose vehicle travel.” That sounds a lot like what SDOT already does, and we know it’s not enough.

I was hoping the report would identify ways the department could dramatically expand on its delivery of safety improvements—especially relatively low-budget safety projects—based on past successes. For example, the Vision Zero team studied the Rainier Ave safety project to death, a process that added a lot of cost and time to their work, which involved little more than painting the lines on the street differently and adjusting some signals and signage. So with that (and many other such studies) in hand, SDOT staff should be able to implement designs like it without such burdensome delays and without needing to wait for a major repaving project. If changing the lines on multi-lane streets would make them safer, then SDOT should be out there changing as many lines as they possibly can. It should be treated as a part of regular maintenance.

We know which streets need to be made safer and we know how to make them safer. This draft of the report contains a lot of good ideas and internal shifts that I hope are meaningful to department staff, but it does not answer the one big question that a lot of people viewing the maps and charts above will be asking: What are we waiting for?

Comments

2 responses to “Draft of SDOT’s Vision Zero review suggests internal reorganizing and more funding, but it feels small compared to our traffic violence emergency”

Last month my uncle insisted he studied every pedestrian death in Seattle and… they were all the pedestrian’s fault. He was convinced of it! My uncle is not remotely qualified to study pedestrian deaths, is car-dependent as hell, and boisterous to any who will listen to boot.

Seattle’s mayor, council, and SDOT really need to ignore the car-dependent ignoramus’ and out-of-town commuters (looking at you Seattle Times) to make the safe street designs exceedingly difficult to deviate from. Mayor Durkan did a massive disservice to the people of Seattle by cancelling the 35th St NE protected bike lane after so much good effort from SDOT. If the political leadership puts the kibosh on SDOT street plans then the public suffers as SDOT goals are obscured, they are rudderless. It is wonderful to read SDOT has the know-how to meet the Vision Zero goals and maddening to read plans weren’t implemented. There is a time to dialog, debate, and discuss, but default street design must hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public. We can settle for nothing less.

“The internal incentives are backwards. An existing street design that we know is dangerous should not be the starting point in the design process. A safe design should the starting point, and SDOT’s internal systems should make the safe street the path of least resistance for project teams.” This is so obvious that there is no way any Seattle politician will ever work to implement it.