In March of 2019, after Mayor Jenny Durkan overrode the finalized plans that the Seattle Department of Transportation had developed for 35th Ave NE in Wedgwood and removed dedicated space for people to bike on that street, it was SDOT who had to go out sell this politically-motivated change. For months, anyone following the issue had seen the opponents of the bike lanes, with well-established ties to the Mayor, push back against the project. SDOT Director Sam Zimbabwe had been officially in his post for only a month before the decision was announced, but the department had to come up with a justification for the change.

One of those reasons cited was the fact that the inclusion of a protected bike lane on 35th Ave NE in the bicycle master plan didn’t adequately take transit into account. Seattle’s bike plan and its transit plan had a conflict on 35th. SDOT’s blog post about the cancelled bike lanes included the fact that “the new design will also allow efficient transit travel through the corridor with southbound buses making in-lane stops at the curb” as opposed to the prior design, which required buses to merge back with traffic after stopping in the bike lane.

Shortly after that, Zimbabwe told Michelle Baruchman of the Seattle Times answering a question about 35th Ave that “we’ve got a lot of modal plans that are getting to be outdated, and how [do] we take those and overlay them to try and work out some of these conflicts at the citywide level, if we can?” The conversation was being turned away from the broken decision-making process onto the city’s long established plans and goals.

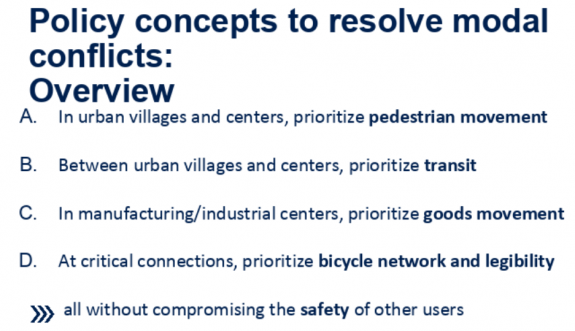

Since then, it looks like this idea that the modal plans don’t “play nice” with each other has taken deeper root at the agency. SDOT has been working on developing an in-house tool that would look at all roadway segments in the city that are “deficient”, meaning they don’t appear to have enough space for the modes in multiple plans, and use a proposed policy framework to resolve those modal conflicts.

So far, we don’t have a good idea yet of where bicycle infrastructure would get prioritized over other modes. According to the policy, “critical connections” would receive priority. Included there is the concept of prioritizing pedestrian movement in all of Seattle’s urban centers and villages, some of the most contested space in the city. “Critical bike segments [would] share priority with pedestrians” in urban villages. There are still a lot of questions about how a critical segment would be defined and how that map would be developed. Right now, it looks like this change will eliminate the bicycle master plan as we know it, and the goals that go along with it, like allowing 100% of the city to live within 1/4 mile of an ALEGRA (all ages, languages, education, genders, races, abilities) bike facility by 2035.

This policy is being developed with SDOT’s Policy and Operations Advisory Group (POAG), which originally convened in response to a council resolution to develop a consistent traffic signal policy, a finalized version of which SDOT released this month. Like this modal prioritization policy, the signal policy was heavily centered around adjacent land use.

At the November POAG meeting, SDOT presented four different examples of how this prioritization might impact outcomes on different street segments. Looking at those concrete examples highlights the shortcomings of the proposed policy.

Elliott Ave W/15th Ave W in Interbay

Elliott Ave W & 15th Ave W are massive (70 foot+) streets with 7 lanes, including curbside Business Access and Transit (BAT) lanes for most of its length. It is not considered “in network” for bicycle facilities, likely because they were not included in the bicycle master plan, even though the nearest parallel bike facility, the terminal 91 bike path, is separated by railroad tracks with a connecting pedestrian bridge. Since the neighborhood is a manufacturing/industrial center, freight access would be at the top of the proposed priority list here, in addition to the transit lanes already in place as part of the frequent transit network. The outcome presented at the meeting is allowing freight to use the bus lanes, turning them into Freight and Transit (FAT) lanes. Additional pedestrian facilities or the impact of reducing auto capacity on the pedestrian environment were not considered here in the exercise.

35th Ave SW in West Seattle

The segment of 35th Ave SW looked at here is not located in an urban village or center, and not on the freight network, but is on the frequent transit network. The current bike master plan indicates that protected bike lanes should be included on the street, but according to SDOT, “This is an unlikely critical bike segment as there are parallel bike routes that are flatter than 35th Ave SW”. It’s unclear what that proposed route would be. Bus-only lanes would be the proposed policy outcome here. It’s important to note that it’s not clear that those bus lanes would even be prioritized if it meant taking away general purpose lanes here, particularly on the busier northern segment of 35th (at least prior to the West Seattle bridge closure). A proposed rechannelization there was scaled back during the current administration.

12th Ave E in Capitol Hill

The only example inside an urban center or village, no buses use this street, though one is proposed in Metro’s long range plan. It’s also a minor truck route. According to SDOT, this is an “unlikely critical bike segment”, even though the paint bike lanes south of Denny Way are probably some of the busiest unprotected bike facilities in the city. This is probably because the Bicycle Master Plan shows a protected bike lane on Broadway north of the existing lane which also ends at Denny Way, not on 12th. Again, it’s not clear how “critical” bike lane segment is defined.

Since it’s inside an urban center, the proposed policy would put pedestrians at the top of the list here: the current sidewalks are half as wide as Seattle’s right-of-way manual says they should be. So the outcome would be to “prioritize future sidewalk widening to meet Streets Illustrated standards”, though it’s hard to imagine a time horizon where that would actually occur. In the meantime, the existing on-street parking lanes would be retained and “strategic widenings at intersections, bike parking, other pedestrian realm uses” would be identified.

In other words, a potential sidewalk expansion in the future justifies keeping things mostly the same in the near-term.

Sylvan Way in West Seattle

Sylvan Way is shown as the example where bicycle facilities would be at the top of the list for prioritization. SDOT called the street an “excellent candidate for designation as a ‘critical bike segment’ because it is one of the few pathways between the Delridge Valley and High Point”. But the current roadway, with two twelve foot travel lanes and a five foot uphill bike lane, is too narrow to add protected bike lanes, so the “options include constructing a multi-use trail side path, or widening the street to accommodate the PBL”. Without a specific grant, that would be likely to eat up a large segment of the bike budget, but it’s possible.

With these four examples, the only space even theoretically proposed to be reallocated away from general purpose vehicles was the bus lane on 35th Ave SW. For advocates of a citywide ALEGRA bike network, it’s hard to see what the benefit will be to moving forward with a watered down “critical segment” version of the bicycle master plan, particularly if it looks to be as skeletal as the examples provided so far have shown.

The biggest thing that seems to be missing from the policy is an actual way to account for how much street space is allocated to none of these modes, but to general purpose traffic. Bryce Kolton, a representative on the POAG from the transit advisory board, told me, “We didn’t even see the words or any term that could be used for the words ‘general purpose traffic’ or ‘single occupancy vehicle’ appear on slides until the fourth meeting”, mentioning that references to the majority of traffic didn’t appear until urging from POAG members.

Kolton is not optimistic that this policy will result in more multimodal projects moving forward. “My question for SDOT, which I have not received a satisfactory answer for, is how come, with all of the plans we have…are we continuously having watered down transportation projects. Why? Until they can tell me why established plans have not been completed when they aren’t for car traffic…I don’t think a multi-multimodal plan is the answer, and I don’t have any faith in them to go back and be able to fix it.”

Anna Zivarts, a pedestrian advisory board representative on the POAG, was slightly more optimistic about the overall goal of the policy. “I think it does need to be a conversation that happens across the modal boards,” she told me. “The question then becomes, is it an equal distribution? How do we then distribute [the street space]? And that I think is what needs to be provided by SDOT or provided by our elected leaders: what is the vision for the city?”

Noting that the policy is still a draft, she added, “From what I have seen, it’s mostly a way of preserving the status quo. I think it makes sense to integrate…if the integration is seen as a way to force the political conversation so the changes can then happen more easily, then that’s helpful, but I’m not sure the city’s going to have the political will to do that.”

SDOT will be presenting a final proposed policy at the next POAG meeting at the end of January. Once it’s finalized, the department will start to use it internally, but SDOT also has a goal of including a citywide integrated transportation map in the 2024 Comprehensive Plan update, which would enshrine these proposed changes even more deeply in city policy. This framework would absolutely play a large role in the development of the transportation levy set to replace Move Seattle at the end of 2024 as well. There’s a lot that could come out of a shift like this, and we have to make sure that it’s not actually a step in the wrong direction.

Comments

8 responses to “The end of the Bicycle Master Plan as we know it?”

This is so discouraging. We know Seattle is not coming close to meeting its GHG emissions reduction goals and yet city government can’t seem to stop itself from prioritizing public space for motor vehicle use and storage. E-bikes and personal mobility devices offer tremendous opportunities to change how we travel, but only if we allocate space for their use.

“So far, we don’t have a good idea yet of where bicycle infrastructure would get prioritized over other modes.”

Are you kidding?

All you have to do is look at precedent and current practice to realize that bicycle infrastructure has always and will always be the lowest priority for SDOT and any other government entity.

The BEST CASE scenarios are places like the BGT and Myrtle Edwards Park – which are shared multi-use infrastructure that have signs indicating ‘bikes yield to pedestrians’

This is disappointing but a plan is not much use without both the desire and competence to implement it and I would argue that we have never really had that. I gather that North Seattle is in better shape than other parts of Seattle but what we have is a hodgepodge of infrastructure with numerous critical gaps and many locations where even on nominally continuous bike routes the (semi-) protected bike lanes give way to sharrows or nothing at the most dangerous intersections.

Using difficulties in modal plan implementation to suggest changes to the Comprehensive Plan is backwards planning. The modal plans are the children, not the parents, of the higher level plans.

It is most important to implement the plans where they have “conflicts”. Those are the places the most people travel using different modes. Those are the most congested places where it is most important to shift people from passenger cars to transit, walking and biking. Those are the places most crashes happen.

The modal plans are written to meet the goals of the Climate Action Plan and 2014 Move Seattle 10-Year Strategic Vision for Transportation. Those plans include the overall strategies to meet the goals of Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan and Seattle’s commitments to regional transportation plans and the State Growth Management Act. The implementation of the Modal Plans must also satisfy the Complete Streets ordinance and land use plans, as shown in the recently revised Right of Way Improvement Manual. When Sam Zimbabwe asks, “how [do] we take those [modal plans] and overlay them to try and work out some of these conflicts at the citywide level, if we can?” The answers should be found by applying the goals and overall strategies of the higher level plans. Those goals include reducing traffic crash fatalities to zero by 2030; a 20% reduction in passenger vehicle miles traveled from 2012 to 2030; and zero net greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

The Climate Action Plan goals for transportation emissions reduction cannot be met without implementation of the Bicycle, Transit, Pedestrian and Freight master plans — all of them, and not just where they don’t have any overlap.

The 2014 Bicycle Master Plan includes these Performance Measure Targets [BMP Table 7-7] which SDOT is failing to measure and failing to meet:

– Ridership: Quadruple ridership from 3.6% in 2014 to 14.4% in 2030.

– Safety: Reduce bicycle collision rate by 50% by 2030.

– Safety: Zero fatalities by 2030.

– Connectivity: 100 percent of bicycle network by 2035.

– Equity: Zero areas of the city lacking bicycle facilities by 2030.

• Serve historically underserved communities first.

– Livability: 100% of households within ¼ mile of all-ages-and-abilities facility by 2035.

The 2016 Freight Master Plan includes strategies and actions for safety and predictable movement of goods that cannot be met without implementing the Bicycle Master Plan for safe bike routes and implementing strategies of the Pedestrian Master Plan. This applies to routes through the industrial areas where all streets are necessarily streets for heavy trucks, and through urban village areas where trucks of all sizes make deliveries on the same busy streets used by buses, bike riders, pedestrians and car drivers.

Implementing the plans and the Move Seattle levy projects is the way to regain support and trust needed for voters to pass the next levy request.

Well, yuck. This just looks like a really bad idea.

Let me start by saying I think people misused the bicycle master plan, treating it like scripture. I do believe there is a place for such planning, but an agency has to be flexible. A bicycle master plan should map out a bike network, and explain why each piece exists. But we shouldn’t assume that each piece will be built as described. It should be aspirational, rather than a compromise, since by its very nature there will be compromises. More than anything, an agency needs to be flexible, and work within the biking community to build what we can build. Money is always an object, as is other, competing interests. Assuming that a single plan will achieve that is folly.

But working off of a largely arbitrary formula to “resolve modal conflicts” is likely to fail, and fail worse. This is dripping with stupid definitions for what is an organic, complex, and ever changing city. It is an attempt to simplify the system, and avoid the dirty work of actually making things work.

Consider some of the definitions: “Urban Villages and Centers”. This is an arbitrary definition of a very anti-urban concept. Basically, the idea is to draw little circles and designate those as “the city”, while the rest of the city is what — the suburbs? Its absurd. The city is full of very urban areas that are growing (let alone urban twenty years ago) that don’t fit the definition. For example, the area just north and east of Gas Works Park has seen dozens of new apartments, and office buildings in the last ten years, and it doesn’t fit any of the definitions of “urban center/village” (https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/OPCD/OngoingInitiatives/SeattlesComprehensivePlan/UrbanVillageElement.pdf#page=8). Oh, and neither to any of the apartments that were built long before Seattle started micro-managing zoning (e. g. Madison Park is not an urban village/center/hamlet/town, despite the existence of building over 20 stories high).

Then there is the focus on manufacturing/industrial centers, which again is arbitrary. There are places where lots of goods must be moved — what difference does it make if it is food for grocery stores, or plastic for a bumper manufacturer in Magnolia? Either way you want to the truck to get through.

Their examples show that this approach is likely to fail. Elliot/15th is a hugely important transit corridor. The bus lanes are not 24 hours — cars are allowed to park in those lanes the rest of the time. It is also important for moving goods. A good compromise would be to make the bus lanes 24 hours, but allow trucks to operate there *outside* of rush hour. Trucking is often done odd hours, to avoid traffic, but if there is traffic there all the time, this would help. Yet the plan could easily cripple transit in this corridor in the name of freight.

35th SW is not as important a transit corridor. But it does have a fairly frequent bus (the 21). It is difficult to build infrastructure that allows bikes and buses to mix. Thus is it quite reasonable for bikes to use a parallel path. But it needs to built to the same standard. Bike riders shouldn’t have to stop at every intersection, or deal with parked cars. There should be stop signs at crossing intersections. At the same time, there should be one-way signs, or blockages that prevent cars from using it as a throughway. There are very few (if any) examples of this, which is part of the problem. As long as the alternatives to bike lanes on major arterials are so bad, people will keep pushing for bike lanes on arterials.

12th should clearly have a bike lane. It is unlikely that Metro will run buses there in the future, making it an obvious choice. It isn’t that far for a walk from Broadway to 12th, but it is a pain on a bike, given the grade. At the same time, from 12th you have easy access to that plateau (https://goo.gl/maps/onbo9fLH4etkKcBx7). You could create an alternative (e. g. 14th) but again, it has to be to the same standard. But the idea that you need to expand the sidewalk just because it is “urban center” is ridiculous. I’m not saying we shouldn’t make the sidewalk bigger — but that is a really bad argument. If there are lots of people, we may need to expand the sidewalk, but it also means that lots of people bike around there (something we know is true).

More than anything, this is just a set of silly, arbitrary rules that will lead to bad, and cowardly decisions. It still opens up the possibility of decisions like 35th Ave NE in Wedgwood. The reason that decision was so bad was not because it went against the master plan, but because there is simply no good alternative for getting up the hill from Meadowbrook to Wedgwood. There is nothing preventing similar poor decisions in the future, and if anything, this will result in more of them.

RossB: Seconding your comment “… people misused the bicycle master plan, treating it like scripture. I do believe there is a place for such planning, but an agency has to be flexible. A bicycle master plan should map out a bike network, and explain why each piece exists.”

That flexibility is explicitly included in the BMP. A lot of people have not even read the scripture — they are only looking at the network map. A plan is not a map. A plan is not a list of projects. The BMP starts with a vision describing who the plan is for, and why. It includes non-project goals like public involvement; equity analysis; end-of-trip facilities; public education programs; traffic law enforcement; maintenance; and funding. It includes a requirement. that SDOT has largely ignored, to measure and report on all of these annually to SBAB and Council.

http://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/SDOT/About/DocumentLibrary/BicycleMasterPlan/SBMP_21March_FINAL_full%20doc.pdf

I often get asked why I would leave the nicest city in America (to move overseas). Now I can include a very concrete anecdote: the parking on 12th avenue is more important than human safety.

Once I’ve paid off my Seattle house, feel free to let us know if you’re hiring any UX researchers. ;-)