Today the City of Seattle has released what it’s calling a “blueprint” to electrify the city’s transportation system, further clarifying the city’s goals around decarbonizing our largest single source of emissions. Among the goals outlined with a 2030 deadline is for the city to create a major area where walking, biking, and transit are the primary modes and goods are delivered by electric or other non-emitting vehicles, and other personal vehicles are restricted.

That goal actually comes directly from a commitment the City made in 2017, when then-Mayor Tim Burgess signed onto a declaration along with eleven other cities from around the world to ensure that a major zone in their city is zero emission by 2030. At the time, Mayor Burgess was quoted alongside Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo as saying, “Responding to climate change’s threat requires big thinking and bold action”. Paris has proceeded with a fundamental reshaping of the city’s streets, with around 30 miles of pop-up bike lanes added in just 2020 that will likely all remain permanent. Seattle built around 2 miles of protected bike lanes last year.

London, another signatory on the 2018 commitment, has already implemented an Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) of around 8 miles in the center of the city, and another Low Emission Zone (LEZ) that covers the rest of the city. Vehicles not meeting certain emission standards are charged to enter the zone; this is separate from the congestion charge also in place in London. Emissions policies like this have had already contributed to a reduction of 44% in roadside NO2 levels in Central London between February 2017 and January 2020 and an an expected 13% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions, according to the Transport Decarbonisation Alliance, C40 cities, and POLIS. These are the public health benefits that come from emissions reduction zones.

In the US, Santa Monica, California is probably the closest example. A pilot project running through this year implemented a voluntary 1-mile emissions-free delivery zone where curb space is reserved for electric delivery vehicles. Personal vehicles used by residents inside the zone are not covered by the voluntary policy.

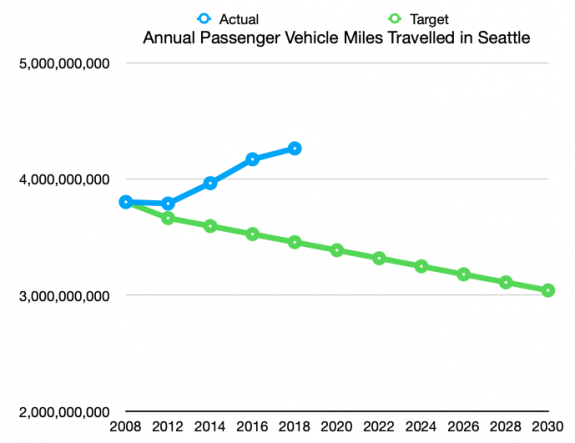

Mayor Durkan has not referenced the 2017 commitment for an emissions-free zone in the city much if at all during her tenure. A 2018 announcement to study congestion pricing as part of “a vision for a more vibrant downtown with fewer cars, more transit, and less pollution” has not produced anything substantive to date. The update to the 2013 Climate Action Plan released in 2018, included very few concrete strategies to reduce Vehicle Miles Travelled (VMT) and shift vehicle trips away from single-occupancy vehicle to transit and active transportation. Seattle’s official 2013 goal for VMT is a 20% drop from 2008 levels by 2030, a modest reduction that the city is currently further away from than when we adopted the goal.

A neighborhood or segment of a neighborhood where most of the cars and trucks permitted to use the streets are delivering goods could amount to one of the biggest shifts of street space to biking and walking ever. Of course, if everyone in Seattle isn’t able to access that emissions-free zone or zones, the impact would be limited and likely inequitable.

The plan spends some time addressing that inequality in the transportation system that our choices continue to reinforce. “Climate justice is a central focus of this plan,” it states. “Our residents and neighbors who are least responsible for climate change and least equipped to adapt, are already disproportionately bearing the health and financial impacts of climate change.” Given that it notes that “residents living in the Duwamish Valley community in South Seattle will die eight years sooner than other Seattle neighborhoods due to air pollution and exposure to environmental toxins”, then that fact should be centered in the urgent task of removing those pollutants, and the emissions that come along with them, from our transportation system.

Among the other 2030 goals in the blueprint is that every single vehicle providing “shared mobility”, including taxis, Uber, Lyft, as well as electric scooter and bike share, is zero-emissions, that 90% of personal trips are in vehicles that are zero-emission, and 30% of goods delivery is completed by zero-emissions vehicles. Having a city-owned fleet that is also 100% zero-emission by 2030 is also a goal. The blueprint states that these “ambitious, yet achievable, goals will accelerate market transformation and make it possible for Seattle to achieve a clean energy future”.

Another plan on the shelf with another set of ambitious goals doesn’t mean much when we aren’t achieving the goals we’ve already set. If we are actually serious about achieving the goals, it’s going to require more specifics and more concrete actions.

Comments

7 responses to “City transportation electrification “blueprint” includes emissions-free area by 2030”

good point at the end — the city budget needs to change to reflect the goals. we need millions more for protected bike lanes, wider sidewalks. the central waterfront rebuild annoys me so much, it should be a big damn park with bike lanes and sidewalks and access for emergency vehicles.

Seattle should print its goals on toilet paper, because then they’d at least be useful. It’s either action or it’s nothing.

The biggest long term lie in America is, cars pay for the roads. The true costs have been intentionally and unintentionally masked for the last 100 years and it clouds our decision making.

Agree with the last point. It’s documented that average resident of Georgetown & South Park has a life expectancy that is 8 years less than the average for Seattle but perpetuating the misinformation that this is all due to air pollution and environmental toxins is disappointing but perhaps the best we can expect from the current city administration.

Electric traction transit is one key tactic. The agencies could improve on Link integration: ST could run Link more often so waits are shorter; ST and Metro could change SR-520 routes to meet Link at the UW station. SDOT bungled the Madison BRT mode; it will not be an electric trolleybus. Metro has some diesel routes running under the trolley overhead (e.g., routes 9, 11, 29). SDOT and Metro could expand the electric trolleybus network and include more frequent routes that have common pathways with the existing overhead. PBL could be added. They are much easier on arterials that do not have transit. Perhaps SDOT and Metro could work together to take service from some; candidates might be 15th Avenue NE north of NE 50th Street and MLK Way north of South Plum Street. In Ballard, we have some bike infrastructure on streets without transit: 17th and 20th avenues NW. Could 28th Avenue NW be another candidate? Why compete with buses? Local streetcars a waste and a danger.

The Mayor’s words are just more words. Show me the budget.

We don’t need new plans before actually implementing existing plans. Unless the goal is just to keep moving targets.

I think the framing of the VMT chart is a little misleading, or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that it doesn’t to my mind convey the message that needs to be conveyed.

The chart is of absolute VMT, not per capita. Per a December 2020 STB article “Seattleites Driving Fewer Miles Than Ever, City Report Suggests,” per-capita VMT has been going down. So to me this indicates that the growth in population is part of the story.

So my other point is that this target of 20% reduction from 2008 to 2030 isn’t modest. It is actually quite aggressive – if it is truly an absolute target, not per-capita target. It’s not the city failing to meet a modest target, but the city failing to meet an aggressive target.

The only way it could be met is through paradigm shift away from car-centric policies (on both the land use and transportation sides) that would underlie across-the-board actions leading to true shifts of density and how people are able to get around, that would lead to meaningful VMT reduction. This shift is challenging due to the contingent of city residents that currently seem to hold the bulk of political power, but it is critically needed for our future.

It seems also that there are also many residents or would-be residents (who would move to Seattle if they could afford it, if housing were made more abundant) that would support a paradigm shift away from car-centric policies. But they don’t seem to hold the power, as evidenced by the ongoing delay and foot-dragging of bike infrastructure improvements and the inertia and resistance to change that is evident whenever zoning discussions come up.