Traffic deaths, especially for people walking, are rising in communities all across the United States, and Seattle is no exception. We have known this increase in deaths is happening, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic changed traffic patterns. But why?

There likely is no single answer to that question because the traffic system in a city is a complex social space. But KUOW recently published an analysis of traffic collision data that points to a few clear factors. Local, state and federal agencies all have major roles to play in making our streets safer, and the responsibility for addressing the problem extends beyond just the transportation agencies.

“Seattle’s homeless, elderly, impoverished and non-white, especially Black, communities continue to bear the brunt of this devastation,” said KUOW reporter Gracie Todd. “And I’ll note that around 20% of pedestrians who die do not have housing.” Addressing traffic deaths relies on addressing inequality and vastly improving human services and housing affordability. These are all huge issues that are intertwined and span nearly every government agency.

One promising bit of news is that the the traffic collision rate for pedestrians has significantly decreased in Seattle. But counterintuitively the traffic fatality rate for pedestrians has increased. Seattle has been successful at preventing more collisions, but those efforts are undermined by other factors that are making the collisions that do occur more deadly.

Todd’s report highlights two big clues about what is leading to the increase in deaths: How wide and fast the road is and how big the vehicle is.

Wide streets are deadly

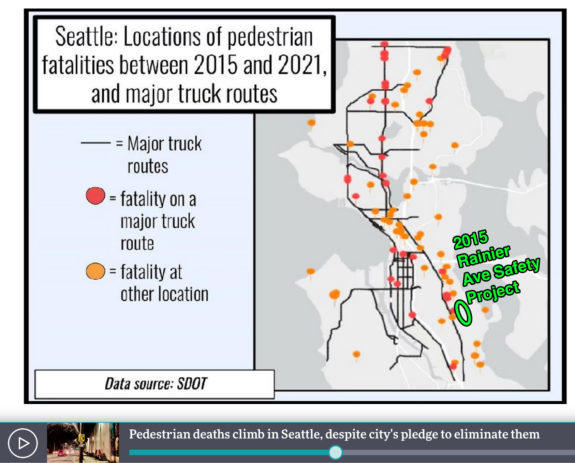

Wider streets encourage faster driving, which we know leads to more serious consequences when things go wrong. But it is still jarring to see how many of the fatal collisions are happening on a small percentage of Seattle’s roads.

Consistently, Seattle’s pedestrian fatalities occur on the busiest, widest, and fastest roads.

Roads where pedestrians died between 2015 and 2021 were, on average, nearly twice as wide as Seattle’s typical road, according to a KUOW analysis of SDOT data.

That analysis also found that arterials — roads split by a yellow line — accounted for over 90% of its pedestrian fatalities, but make up less than a third of Seattle’s road network.

Even more lopsided, over half of those pedestrians were killed on major truck routes, a subcategory of arterials that make up just 8% of Seattle’s roads.

One of the big questions of the story is whether Seattle’s Vision Zero program is failing. But the streets where most of these deaths occur are not the ones that have received significant Vision Zero safety improvements. Many, like Aurora, are state highways that SDOT manages. Others, like Rainier Ave, have seen significant safety improvements on the sections where SDOT took action. But much of the street remains unimproved and, therefore, continues to see a huge number of serious collisions. If you look at a map of fatal collisions from 2015-2020, you can almost see where the 2015 Rainier Ave safety project begins and ends just by plotting the dead bodies.

Also missing from the map are Nickerson, Stone Way, NE 125th Street and most other sites of controversial road safety projects completed in the years shortly before 2015. And those older safety redesigns even fall short of the city’s current best practices. The problem isn’t that the Vision Zero program is failing, it’s that we are not investing in Vision Zero on many of our most dangerous streets.

“There have been some successes,” said Todd in the radio segment. “Again, that rate of collisions has declined. And when Vision Zero has implemented projects, putting in safety features at intersections, redesigning the roads a bit, many of these have shown really promising results.” Allison Schwartz, SDOT’s Vision Zero Coordinator, told Todd something similar.

“For decades, our streets and our cities have really been planned and designed around the fast and efficient movement of vehicles, and it hasn’t necessarily been centered on the safe movement of human beings,” said Schwartz. “There are promising, positive movements where we do make investments, it’s just scaling that up, being able to do that at a citywide level, comes with challenges and is going to take time.”

Todd spoke with a vice-mayor in Oslo, Norway, about their far more successful Vision Zero efforts, and came to a couple conclusions. First, the city needs to be “fundamentally redesigning the roads.” That means narrowing roads and adding more stops and roundabouts that can slow people down. And our society needs to shift a large share of the responsibility for safety from users to road design. “We know that people make mistakes. That’s kind of outside any agency’s control. But roads can make those mistakes much less catastrophic.”

Achieving Vision Zero is going to require a huge effort from all levels of government. But it’s a very worthy and achievable goal. We know how to get there because we’ve done it. But so far, Seattle has only been improving a handful of streets per year. We need an effort that treats SDOT’s Vision Zero project to date as though it were a pilot project. The real results will come from dedicated action from the top down in every project from every agency. As KUOW’s Seattle Now host Patricia Murphy put it, “That’s going to take a lot more than one Vision Zero office staff of people, Gracie.”

Larger vehicles are deadly

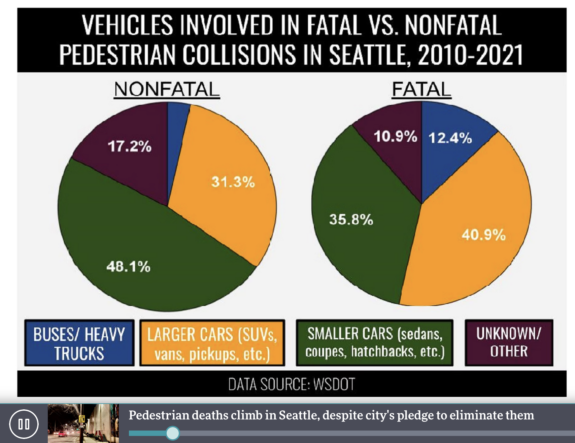

The second outlier in the recent fatality data that Todd highlights is the increasing size of trucks and SUVs.

“Heavier passenger cars, things like trucks and SUVs, are involved in 30% of non-fatal pedestrian collisions but then about 40% of fatal pedestrian collisions,” Todd reported, citing Washington State collision data. “There’s this over-representation in large vehicles being involved in fatalities.”

Larger, heavier vehicles have a number of major safety flaws. The added weight means that the vehicles have more energy than a smaller vehicle traveling the same speed. This can make slowing and stopping more difficult and collisions more devastating. The height of large vehicle hoods also makes it more difficult for drivers to see people walking or biking in front of them. The taller hood also increases the harm to people they strike. Hitting someone higher up on their body is more deadly because it knocks them back rather than up onto the hood. This results in both a more deadly initial collision while also sending the injured person to the ground where someone might run them over.

The auto industry has made it very clear that they will not address these glaring safety issues unless government regulations force them to. Unfortunately, the city does not have the ability to regulate vehicle design. That responsibility falls primarily to the Federal government, though states could also potentially flex their power. For example, if a few states partnered to mandate safer vehicle designs, that could effectively force the whole industry to adapt.

The hopeful part of this story is that we know how to make progress to save more people from death or serious injury. We just need to dramatically expand our implementation of proven safety fixes.

That 2015 Rainier Ave safety project was championed by then-City Councilmember Bruce Harrell. He is now mayor, so he has an opportunity to finish the job. He can also develop a transportation funding measure that extends that demonstrated success, a project that has certainly saved people’s lives, to the rest of the city.

Meanwhile, the state legislators have been hearing WSDOT leaders call for investments in safety improvements along state highways, which includes some of Seattle’s most deadly streets like Aurora and Lake City Way. WSDOT roads are very often the most dangerous streets in any Washington community, so this could be a huge deal for safety. Legislators currently have the opportunity to pass a funding package that puts serious money behind such a safety effort.

And finally, the Feds. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg keeps saying the right things about making safety the actual top priority for the nation’s transportation efforts. Will the Biden Administration take action to improve vehicle safety and better fund safety improvements in communities across the nation?

We would never tolerate 3,000 deaths per month on America's airlines or subways, but on our roads we act like it's normal.

It's time for a new mentality for roadway safety.

— Secretary Pete Buttigieg (@SecretaryPete) January 31, 2022

Comments

4 responses to “KUOW: Larger vehicles on wide roads are at the center of Seattle’s rising traffic death toll”

Some transportation planners and active transportation advocates are labeling these “streets” with a new term: Stroads. They are not good streets and they are not good roads. They are ineffective as streets and as roads. They are deadly. They are the result of 70 years of misplaced emphasis and misunderstanding of induced demand, which is the long known reality that traffic increases to fill the space. Your juxtaposition of the eyeopening graphic about fatalities and vehicle sizes with the map of deadly streets makes me ponder that planners need a new corollary to the well known axiom that bigger streets and roads lead to more traffic. Suggested corollary: bigger streets and roads lead to drivers who want bigger vehicles and more speed.

It seems to me that most of the fatalities can be organized into a few clusters: 1) All of Aurora, especially the north, is a disaster area; 2) SODO and the industrial district; 3) a cluster at the far north of LCW; and 4) a cluster at 15th & Dravus.

The trouble with SODO and Aurora is that any attempt to seriously change the streets to be less car-sewery will be fought by well-organized local business and industry opposition. Even setting that aside, establishing property boundaries and proper driveways, and building long stretches of new sidewalk in areas that are already developed, is shockingly expensive. I know it needs to be done but I just can’t bring myself to be optimistic about it happening.

15th & Dravus just needs to be un-grade-separated. The weird H interchange with tiny sidewalks is an unfixable relic of the build-freeways-everywhere era, and it makes no sense on that road which has several lights to the south. Just fill the underpass, narrow the road and put in a traffic light. Preferably do this before the light rail station nearby gets built.

Certainly, larger vehicles, speed, and intersection crossing distance are important factors. Lower speeds, sideguards on trucks, no-right-on-red, pedestrian leading signals, and better intersection design on major truck streets can help. Two contrarian comments on this report:

1. Beware the statistical fallacies of small numbers. There can be huge swings from year to year.

2. More serious injuries and fatalities are on larger streets because those are where the traffic is.

I agree fully with your last point. Obviously, the arterial network takes up only a relatively small percentage of Seattle roads by distance. But I’m fairly sure that they take up a much larger percentage by vehicle miles traveled. That is the proper comparison. It doesn’t change the recommendations of the article, but it’s not helpful to use the wrong statistics.