The Seattle Department of Transportation has released its proposed spending plan for the proceeds from a $20 vehicle license fee (VLF) that the City Council approved last fall. After an outreach process where the department received feedback from around 20 organizations and boards, it’s sending these funding recommendations back to the Council early next month. The VLF is expected to raise around $3.6 million in 2021 after it takes effect mid-year and around $7 million per year starting in 2022.

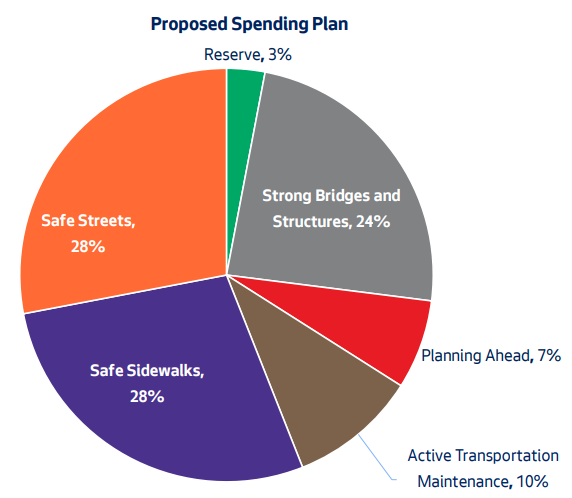

In budget discussions last year, a bloc of three councilmembers proposed allocating the entire amount toward bridge maintenance. A report from the city auditor had highlighted a spending gap on bridge maintenance funding: average spending on bridge maintenance of $6.6 million per year compared to a conservative estimate of $34 million per year. This plan would only spend around $2 million on bridge maintenance, in the “strong bridges and structures” category, which has been broadened to include stairways and other “essential roadway structures”. That’s approximately one-quarter of the revenue generated.

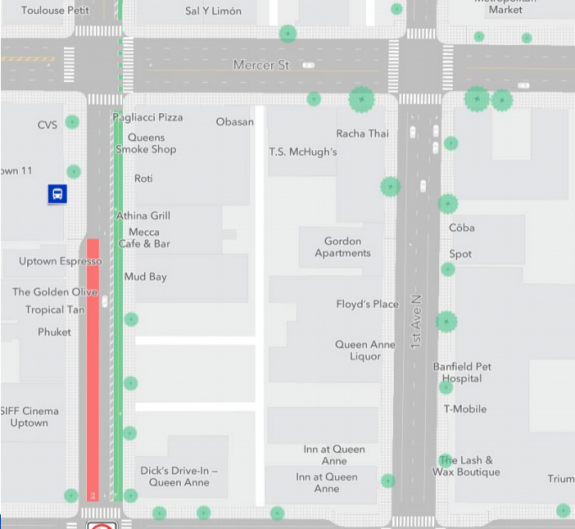

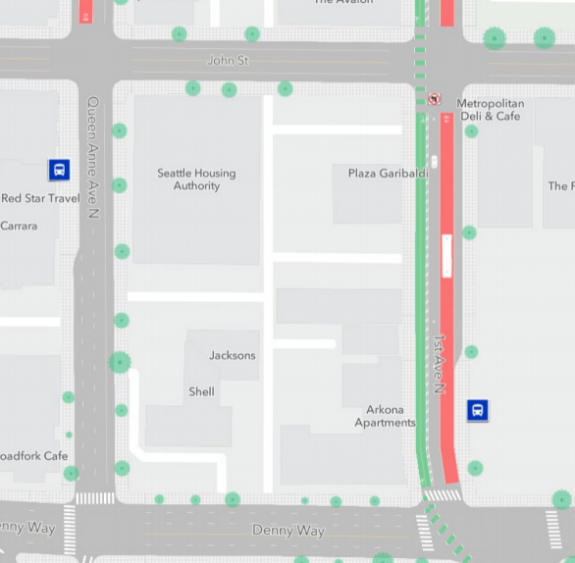

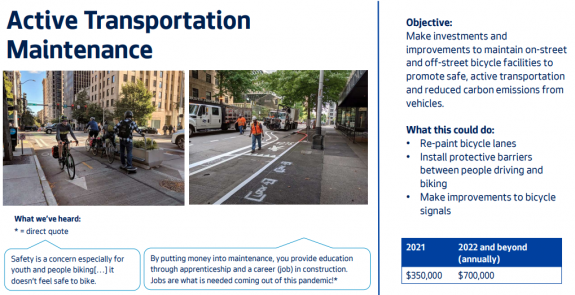

But a large percentage of the overall revenue is still earmarked for transportation maintenance. 28% of the revenue would go toward “safe sidewalks”, which includes restriping crosswalks, replacing crossing beacons, and repairing existing sidewalks. Money in this category would also be used to fund ADA curb ramps, which the city is under a court-mandated order to do. Another 10% would go to “active transportation maintenance”, which includes repainting bike lanes, upgrading barriers on protected lanes, and bike signal improvements.

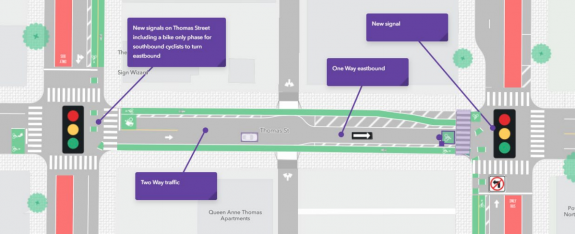

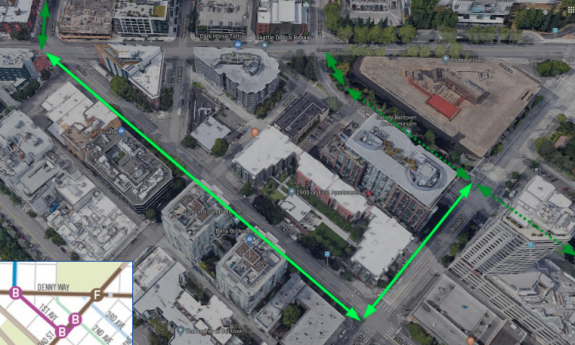

Another 28% of revenue would be dedicated to safe streets through Vision Zero projects. Vision Zero projects run the gamut in scope, from spot improvements at a single intersection to protected bike lane installation on an entire corridor. The department was already on track to complete all of the VZ projects (12-15) that it promised to deliver with the Move Seattle levy, but the process for prioritizing those remains opaque and we’ve seen specific projects during the Durkan administration watered down.

Another 7% would be allocated to planning, which includes the development of a citywide multimodal plan. The city doesn’t lack in plans, just the vision to implement them and frequently (but not always) the funds to complete them. The details we’ve seen so far on the development of a citywide multimodal plan actually seem to get us farther away, with the bicycle master plan getting dismantled in the name of identifying “critical segments”.

3% of the funds would be kept in reserve, rounding out the entire pie.

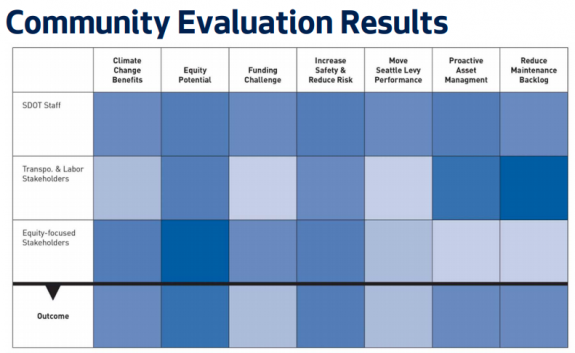

How we got to this point is not completely clear. According to the results of SDOT’s outreach, the highest rated criteria for prioritization in the process was increasing equity in Seattle’s transportation system, with increasing safety close behind. While reducing the maintenance backlog was prioritized highly by stakeholders in the “transportation and labor” space, it didn’t come out on top when the results were weighted across the entire group of feedback providers. But equity and safety are core values at the Seattle Department of Transportation, as well as sustainability and mobility.

David Seater, former chair of the Pedestrian Advisory Board and a participant in the outreach process for this spending plan, told me that the public outreach was frustrating, particularly the idea of having to choose between safety and equity. “This process seems like a huge amount of overhead for what is a relatively small amount of money in the context of the SDOT budget. SDOT already has a huge, rigorously prioritized backlog of work and we should just be following that as more money becomes available”, he told me.

Ultimately the issue is that we’re trying to get too many things from one $20 vehicle license fee. If we need the entire amount here to fund bridge maintenance so we don’t have to spend more later, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t push for other revenue sources to fund all of the other urgently needed priorities outlined in this spending plan. The size of the pie is a bigger issue than the individual slices.

SDOT has a survey on these spending categories through March 30th at 9am.