This week SDOT told the Bicycle Advisory Board that an extension of the 4th Avenue protected bike lane downtown, to both the north and the south, is moving forward with construction planned for this Spring. With those extensions, the entire facility will be converted to a two-way bike lane compared to the current configuration which is only two-way in central downtown.

At the meeting, SDOT provided a closer look at the planned design of the lanes. To the north, the PBL will be extended from Bell to Vine Street, adding protected left turn signals to separate people riding bikes from turning drivers. We haven’t seen what the end of the bike line looks like at Vine (probably a green bike box to make a right turn onto Vine), but the northern extension as a whole should look pretty much like it does in the rest of Belltown currently.

It’s the south end where things will get a little tricky. The lane on 4th Ave is only planned to go to Dilling Way. What’s Dilling Way? It’s just north of Yesler, the curved street that connects 4th and 3rd right next to City Hall Park. SDOT is planning a two-way PBL on the north side of Dilling Way, retaining parking on the south side of the tiny street.

At 3rd Avenue, people riding will use a ramp to access the sidewalk to queue for the light to change. This is probably the most unfortunate element of this planned connection: routing a bike facility onto a sidewalk should be avoided at all costs. This is pretty reminiscent of the plan for the north end of the 2nd Ave PBL, except this is right in the middle of the route, not the end. SDOT said they are planning on doing some work to improve the sidewalk here, but this will particularly impact blind and low-vision pedestrians who are not expecting to be walking in a bike mixing space.

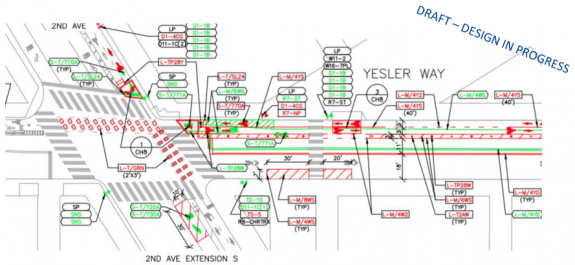

Here’s a closer look at the plans for this segment, via a draft design document presented this week. You can see in the diagram that people riding bikes will use a ramp to enter and exit the 3rd and Yesler sidewalk that is separate from the ADA ramp. The crosswalk across 3rd will be completely redone to make it wider to accommodate people walking, rolling, and biking.

On the block between 3rd Ave and 2nd Ave, the two-way PBL stays on the north side of the street, connecting with the 2nd Ave PBL and the Yesler stub lane currently in place on the other side of 3rd Ave. Eventually this will connect all the way to the Waterfront bike route but funding hasn’t been secured for that short connection yet.

Why isn’t the 4th Ave PBL connecting with the already installed bike lanes in Pioneer Square on Main Street? SDOT contends that a bike lane between Yesler and Main isn’t feasible because of the volumes of buses that use the corridor. The connection is eventually planned, SDOT says, but not until 2023 or 2024, after both the Northgate and East Link light rail extensions convert more bus trips to light rail trips.

The installation of a two-way facility on most of 4th Ave this year will be a huge win, given the fact that delaying this bike lane was one of Mayor Durkan’s first acts on taking office.