“Not accomplishing anything” is how Tim Parham, the Director of Real Estate Development at Plymouth Housing Group described the current requirement to include a secure bike parking room in all of the buildings it constructs as Permanent Supportive Housing. Plymouth Housing Group is one of the largest providers of very low-income housing in Seattle and maintains 17 buildings with over 1,000 residents.

What exactly is Permanent Supportive Housing? From King County: “Permanent supportive housing is permanent housing for a household that is homeless on entry, where the individual or a household member has a condition of disability, such as mental illness, substance abuse, chronic health issues, or other conditions that create multiple and serious ongoing barriers to housing stability”.

With Seattle and King County now in a homelessness State of Emergency for over five years, building as much housing like this as fast as possible should remain our goal. In 2020, the Office of Housing announced $60 million to be invested in Permanent Supportive Housing to build nearly 600 units, but thousands of people currently living on Seattle’s streets need units like these. Public dollars get combined with private ones to create more housing than direct city investment, but the projects still have to go through most of the same bureaucratic hoops new market-rate development does, even as it saves lives that may have been lost if people continue to live on the street.

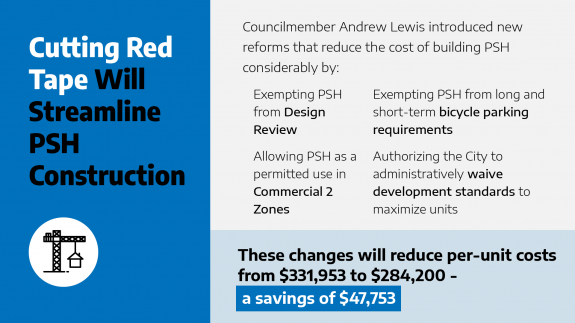

District 7 Councilmember Andrew Lewis has proposed a package of land use reforms intended to speed up, and reduce the per-unit costs on, construction of PSH. As a whole, the package of changes could reduce costs for each individual unit of housing by over $47,000, or almost 15%. One of these is the exemption from the bicycle parking requirements that normally apply to multifamily residential development.

Tim Parham told me that an average bike room in a building being built for Permanent Supportive Housing costs Plymouth around $300,000- essentially the cost of a single unit of housing that could change a person’s life. And that bike parking room often takes up some of the most valuable (and therefore most costly) real estate in the entire building- space that could be used for a nurse’s station, for example, or a community room.

He explained that the demographics of the people that Permanent Supportive Housing is intended for tend to skew heavily away from utilizing secure bike parking rooms. If someone living in PSH does have a bike, “it tends to be the most valuable thing they own”, which makes them likely to want to keep their bike in their unit. He told the city council’s Select Committee on Homelessness Strategies and Investments that Plymouth is moving toward including hooks for bike storage within the units themselves. At that meeting, Derrick Belgarde of the Chief Seattle Club also echoed the frustration with having to balance a bike parking room against other amenities that they might want to be providing when the proportion of people who would ultimately use that bike room remains relatively low.

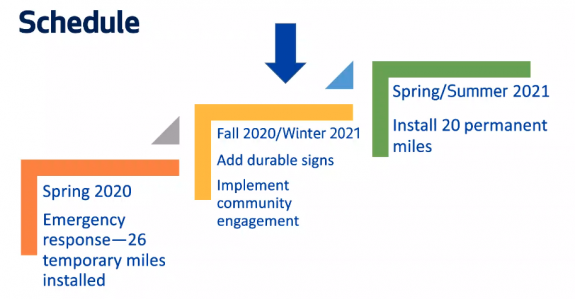

I am focusing on the bike parking aspect here for obvious reasons, but the legislation would also remove Permanent Supportive Housing buildings from all design review, also a prime cause for delay in getting housing built. You can read about all aspects of the legislation here. The city council’s select committee on homelessness met to discuss the bill in mid-December and will be picking it up again with another meeting later this month; there will be a public hearing on the proposal on Wednesday January 27, specific meeting details still pending. Now is the time to contact your councilmembers about supporting this proposal that could save lives.

The Washington legislature’s long legislative session starts next Monday. This is set to be an important session as lawmakers modify Governor Inslee’s proposal for the biennial budget.

The Washington legislature’s long legislative session starts next Monday. This is set to be an important session as lawmakers modify Governor Inslee’s proposal for the biennial budget.