Seattle’s Complete Streets ordinance turns 14 years old this year. Since becoming one of the first major American cities to codify in city law the idea that all major transportation improvements should include accommodations for all types of street users, the city has struggled to actually put this into practice. Loopholes allowed individual projects to be exempt from the ordinance. In 2019, after SDOT made it crystal clear how toothless the ordinance was by completing a Complete Streets checklist on 35th Ave NE in Wedgwood (after the department redesigned the street to include no bike facilities at the direction of the Mayor), the City Council passed another law requiring major repaving projects to include bike facilities if they are designated on the Bicycle Master Plan.

Now, it looks like the Seattle Department of Transportation is ready to throw in the towel on the Bicycle Master Plan entirely, and along with it all of the plan’s goals and benefits, under the guise of integrating all of the City’s modal plans together.

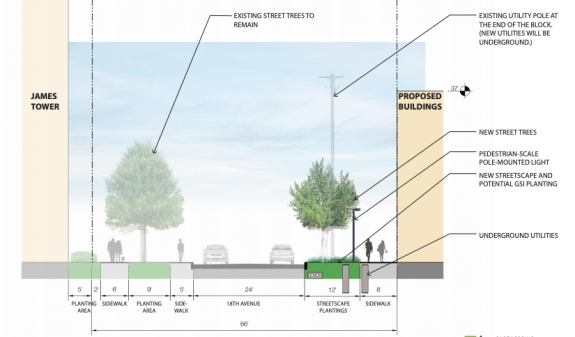

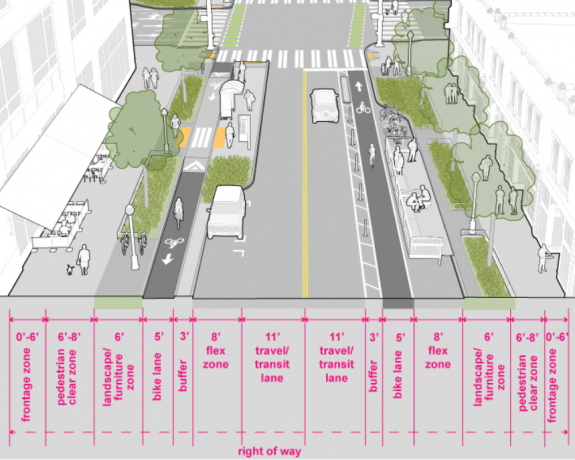

Last Thursday SDOT held its final meeting with the Policy and Operations Advisory Group (POAG) and presented a finalized draft “modal integration policy framework”. We previewed this framework after the group’s last meeting in December. According to the department, it was developed to create policy guidance on integrating the bicycle, transit, freight, and pedestrian master plans. It focuses on areas where the right of way is “deficient”, meaning that according to SDOT’s own design standards (as laid out in its Streets Illustrated Right-of-Way improvement manual) there isn’t enough room to accommodate all modes on a specific city block. “Even with a large policy foundation, we lack comprehensive policy guidance for how accommodate these networks in places where the [street] is too narrow for all desired modes and uses,” the policy’s executive summary states.

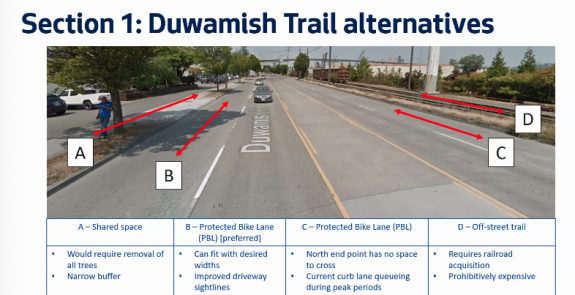

That executive summary, which is the most detailed summary of the policy that we’ve seen so far, makes it even more clear that the adoption of this policy would specifically target the Bicycle Master Plan over the other modal plans. Across the three adopted modal plans (with the Pedestrian Master Plan analyzed separately), it cites 5,269 segments of bike lane, transit lane, or freight lane intended to fit within the space available from one curb to another. SDOT says 8% of them, or 440 blocks, are not wide enough to accommodate all of the modes specified as needing space in their respective plans. Amazingly, all but one of those 440 includes a planned bike facility. On half of those blocks (223), the bicycle facility is the only thing even competing for extra street space- no transit lanes or freight lanes are even conceived on those blocks.

In other words, if the Bicycle Master Plan didn’t exist, there would be one block of conflict between Seattle’s modal plans over the use of the curb-to-curb space on our streets.

In addition, there are another 1,208 street segments where a planned bike, freight, or transit lane fits in the street space only if a turn lane or a flex lane (parking, loading, peak hour travel) were removed. Again, this is almost entirely (598 of these) a bike facility all by itself. The policy states that flex lanes “in some cases, should be prioritized in right-of-way allocation decisions, and should be evaluated more consistently within concept design processes”.