The Washington State House of Representatives Transportation Committee convened for the first time this session on Tuesday and WSDOT head Roger Millar was there to lead the members through a presentation, which was titled “Return on Investment”.

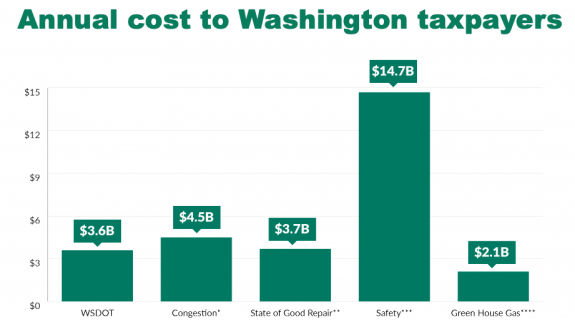

At the beginning of the talk, he made sure to emphasize that the legislature calls the shots and selects the projects, not WSDOT. But the framing of the presentation was focused on what kinds of investments might produce a higher return for the state as a whole. And he showed the committee a slide that broke down different categories where those costs are currently playing out.

Safety was the biggest impact shown. The annual cost of traffic crashes that happen because our transportation system isn’t safe enough was pegged in his data at $14.7 billion per year, which is over four times the actual budget of WSDOT itself. And it’s over 3.2 times as much as the cost attributed to “congestion” which the legislature seems much more preoccupied with.

“If we could drive these numbers down by increasing what we spend on transportation, we could have that increased investment and actually save hardworking families and hardworking businesses some money on the way”, he told the committee members. Of course, we could save much more than money by improving safety in the transportation system, we could save lives and prevent devastating life-altering injuries. It’s actually absurd to put this side-by-side with a so-called cost to sitting in traffic, but given the legislature’s track record clearly necessary.

What Millar did not do is directly connect the dots on safety, but his agency is doing that right now, in part with the Active Transportation Plan. Spending $283 million on adding speed treatments to every single state highway through a population center would save lives. So would spending $165 million to improve safety at every single highway ramp in the state. Or $1.2 billion to add full pedestrian facilities along state highways.

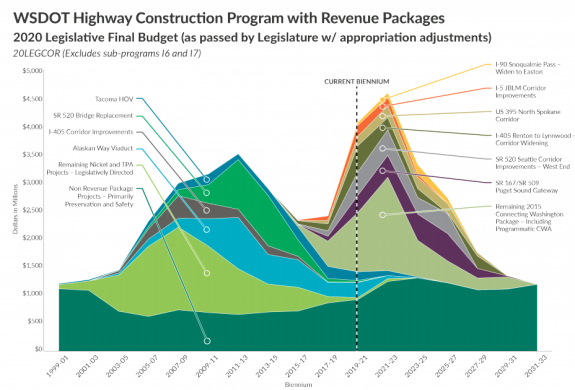

Millar’s speech to the committee comes at a time when, according to slides in his presentation, Washington is set to spend more money maintaining and expanding the state highway than it ever has before. This was conveyed in a chart showing highway construction heading toward a peak of nearly $5 billion in the next biennium as so many different highway expansion projects are set to be under construction at the same time.

Secretary Millar also tried to make the argument against highway expansion from the perspective of jobs creation, citing numbers showing that bicycle projects create 46% more jobs per million dollars spent than car-only road projects, and that public transit projects create 31% more jobs.

Clearly leadership at the state’s transportation agency wants to take the state in the right direction but, again, they don’t choose the projects to build. Roger Millar’s presentation this week should set the stage for making smarter investments than we have made in the past, with Senator Saldaña’s Evergreen Package an obvious vehicle for that, but only if we are ready to push against the status quo.