In March of 2019, after Mayor Jenny Durkan overrode the finalized plans that the Seattle Department of Transportation had developed for 35th Ave NE in Wedgwood and removed dedicated space for people to bike on that street, it was SDOT who had to go out sell this politically-motivated change. For months, anyone following the issue had seen the opponents of the bike lanes, with well-established ties to the Mayor, push back against the project. SDOT Director Sam Zimbabwe had been officially in his post for only a month before the decision was announced, but the department had to come up with a justification for the change.

One of those reasons cited was the fact that the inclusion of a protected bike lane on 35th Ave NE in the bicycle master plan didn’t adequately take transit into account. Seattle’s bike plan and its transit plan had a conflict on 35th. SDOT’s blog post about the cancelled bike lanes included the fact that “the new design will also allow efficient transit travel through the corridor with southbound buses making in-lane stops at the curb” as opposed to the prior design, which required buses to merge back with traffic after stopping in the bike lane.

Shortly after that, Zimbabwe told Michelle Baruchman of the Seattle Times answering a question about 35th Ave that “we’ve got a lot of modal plans that are getting to be outdated, and how [do] we take those and overlay them to try and work out some of these conflicts at the citywide level, if we can?” The conversation was being turned away from the broken decision-making process onto the city’s long established plans and goals.

Since then, it looks like this idea that the modal plans don’t “play nice” with each other has taken deeper root at the agency. SDOT has been working on developing an in-house tool that would look at all roadway segments in the city that are “deficient”, meaning they don’t appear to have enough space for the modes in multiple plans, and use a proposed policy framework to resolve those modal conflicts.

So far, we don’t have a good idea yet of where bicycle infrastructure would get prioritized over other modes. According to the policy, “critical connections” would receive priority. Included there is the concept of prioritizing pedestrian movement in all of Seattle’s urban centers and villages, some of the most contested space in the city. “Critical bike segments [would] share priority with pedestrians” in urban villages. There are still a lot of questions about how a critical segment would be defined and how that map would be developed. Right now, it looks like this change will eliminate the bicycle master plan as we know it, and the goals that go along with it, like allowing 100% of the city to live within 1/4 mile of an ALEGRA (all ages, languages, education, genders, races, abilities) bike facility by 2035.

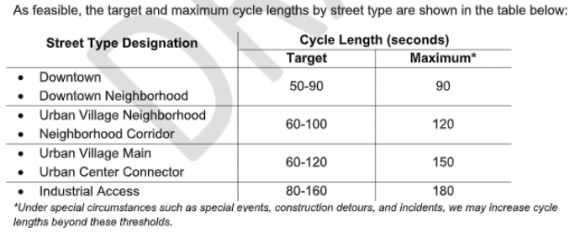

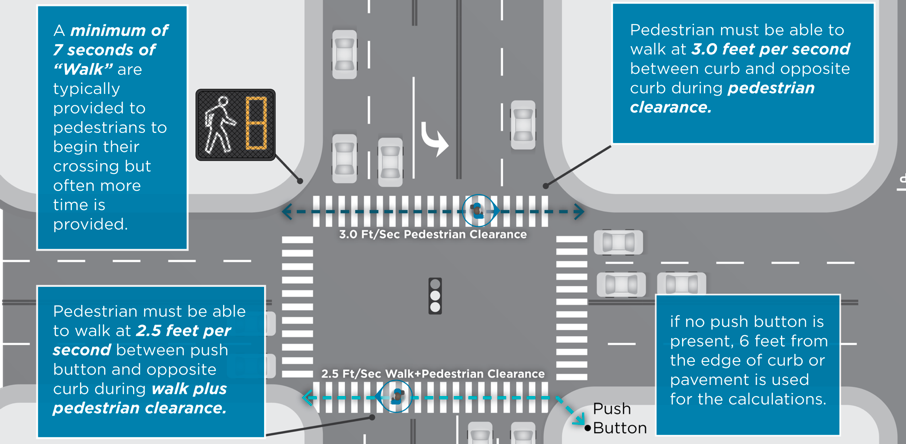

This policy is being developed with SDOT’s Policy and Operations Advisory Group (POAG), which originally convened in response to a council resolution to develop a consistent traffic signal policy, a finalized version of which SDOT released this month. Like this modal prioritization policy, the signal policy was heavily centered around adjacent land use.

At the November POAG meeting, SDOT presented four different examples of how this prioritization might impact outcomes on different street segments. Looking at those concrete examples highlights the shortcomings of the proposed policy.

Elliott Ave W/15th Ave W in Interbay

Elliott Ave W & 15th Ave W are massive (70 foot+) streets with 7 lanes, including curbside Business Access and Transit (BAT) lanes for most of its length. It is not considered “in network” for bicycle facilities, likely because they were not included in the bicycle master plan, even though the nearest parallel bike facility, the terminal 91 bike path, is separated by railroad tracks with a connecting pedestrian bridge. Since the neighborhood is a manufacturing/industrial center, freight access would be at the top of the proposed priority list here, in addition to the transit lanes already in place as part of the frequent transit network. The outcome presented at the meeting is allowing freight to use the bus lanes, turning them into Freight and Transit (FAT) lanes. Additional pedestrian facilities or the impact of reducing auto capacity on the pedestrian environment were not considered here in the exercise.

35th Ave SW in West Seattle

The segment of 35th Ave SW looked at here is not located in an urban village or center, and not on the freight network, but is on the frequent transit network. The current bike master plan indicates that protected bike lanes should be included on the street, but according to SDOT, “This is an unlikely critical bike segment as there are parallel bike routes that are flatter than 35th Ave SW”. It’s unclear what that proposed route would be. Bus-only lanes would be the proposed policy outcome here. It’s important to note that it’s not clear that those bus lanes would even be prioritized if it meant taking away general purpose lanes here, particularly on the busier northern segment of 35th (at least prior to the West Seattle bridge closure). A proposed rechannelization there was scaled back during the current administration.

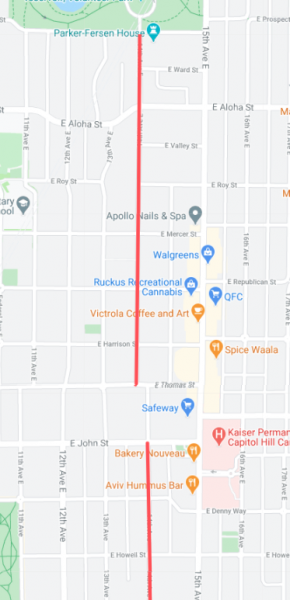

12th Ave E in Capitol Hill

The only example inside an urban center or village, no buses use this street, though one is proposed in Metro’s long range plan. It’s also a minor truck route. According to SDOT, this is an “unlikely critical bike segment”, even though the paint bike lanes south of Denny Way are probably some of the busiest unprotected bike facilities in the city. This is probably because the Bicycle Master Plan shows a protected bike lane on Broadway north of the existing lane which also ends at Denny Way, not on 12th. Again, it’s not clear how “critical” bike lane segment is defined.

Since it’s inside an urban center, the proposed policy would put pedestrians at the top of the list here: the current sidewalks are half as wide as Seattle’s right-of-way manual says they should be. So the outcome would be to “prioritize future sidewalk widening to meet Streets Illustrated standards”, though it’s hard to imagine a time horizon where that would actually occur. In the meantime, the existing on-street parking lanes would be retained and “strategic widenings at intersections, bike parking, other pedestrian realm uses” would be identified.

In other words, a potential sidewalk expansion in the future justifies keeping things mostly the same in the near-term.

Sylvan Way in West Seattle

Sylvan Way is shown as the example where bicycle facilities would be at the top of the list for prioritization. SDOT called the street an “excellent candidate for designation as a ‘critical bike segment’ because it is one of the few pathways between the Delridge Valley and High Point”. But the current roadway, with two twelve foot travel lanes and a five foot uphill bike lane, is too narrow to add protected bike lanes, so the “options include constructing a multi-use trail side path, or widening the street to accommodate the PBL”. Without a specific grant, that would be likely to eat up a large segment of the bike budget, but it’s possible.

With these four examples, the only space even theoretically proposed to be reallocated away from general purpose vehicles was the bus lane on 35th Ave SW. For advocates of a citywide ALEGRA bike network, it’s hard to see what the benefit will be to moving forward with a watered down “critical segment” version of the bicycle master plan, particularly if it looks to be as skeletal as the examples provided so far have shown.

The biggest thing that seems to be missing from the policy is an actual way to account for how much street space is allocated to none of these modes, but to general purpose traffic. Bryce Kolton, a representative on the POAG from the transit advisory board, told me, “We didn’t even see the words or any term that could be used for the words ‘general purpose traffic’ or ‘single occupancy vehicle’ appear on slides until the fourth meeting”, mentioning that references to the majority of traffic didn’t appear until urging from POAG members.

Kolton is not optimistic that this policy will result in more multimodal projects moving forward. “My question for SDOT, which I have not received a satisfactory answer for, is how come, with all of the plans we have…are we continuously having watered down transportation projects. Why? Until they can tell me why established plans have not been completed when they aren’t for car traffic…I don’t think a multi-multimodal plan is the answer, and I don’t have any faith in them to go back and be able to fix it.”

Anna Zivarts, a pedestrian advisory board representative on the POAG, was slightly more optimistic about the overall goal of the policy. “I think it does need to be a conversation that happens across the modal boards,” she told me. “The question then becomes, is it an equal distribution? How do we then distribute [the street space]? And that I think is what needs to be provided by SDOT or provided by our elected leaders: what is the vision for the city?”

Noting that the policy is still a draft, she added, “From what I have seen, it’s mostly a way of preserving the status quo. I think it makes sense to integrate…if the integration is seen as a way to force the political conversation so the changes can then happen more easily, then that’s helpful, but I’m not sure the city’s going to have the political will to do that.”

SDOT will be presenting a final proposed policy at the next POAG meeting at the end of January. Once it’s finalized, the department will start to use it internally, but SDOT also has a goal of including a citywide integrated transportation map in the 2024 Comprehensive Plan update, which would enshrine these proposed changes even more deeply in city policy. This framework would absolutely play a large role in the development of the transportation levy set to replace Move Seattle at the end of 2024 as well. There’s a lot that could come out of a shift like this, and we have to make sure that it’s not actually a step in the wrong direction.