EDITOR’S NOTE: Yes Segura was already researching the role of policing in traffic enforcement before I started working on this story. So I worked with him over the past week to put this piece together. As the city opens the police budget to scrutiny, it’s vital that we look back to our history to learn how police ever got involved in traffic enforcement in the first place. Before diving into the budget details, Seattle should take a big step back and ask some for foundational questions about the racist web of a criminal justice system we have created and how traffic enforcement is very often the point of entry for Black people and people of color who get caught in it.

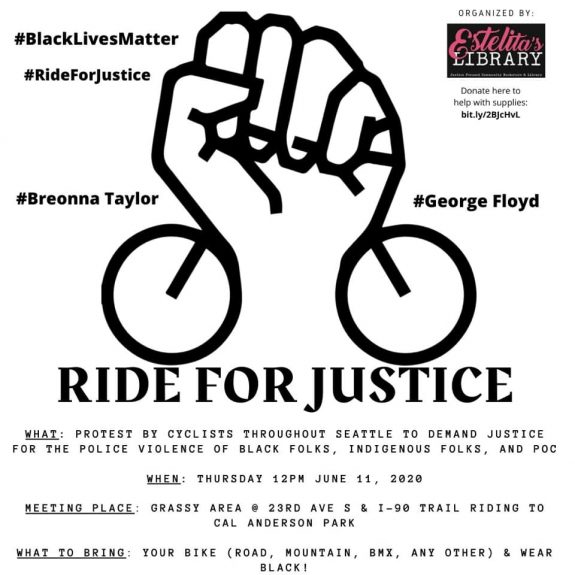

Protests are happening in Seattle and throughout the world in solidarity to support Black lives. This Civil Rights movement comes from the recent videos and stories of Charleena Lyles, Manuel Ellis, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Tony McDade, Sandra Bland, Michael Brown and the endless list of BIPOC lost to police violence #SayTheirNames.

The City of Seattle is one of many cities considering defunding police, but what exactly does that look like within transportation? Police enforcement within transportation has sustained racial inequity. From biking to riding the light rail to taking the bus to walking and to driving, police power is ingrained into every mode of transportation. Here’s the catch though, if you are not Black, Indigenous, and or a Person of Color (“BIPOC”), you haven’t faced what it’s like to be disproportionately targeted by the police just because of the color of your skin. It means you could be facing life or death, and if it isn’t death it’s likely going to be a life burden in some form or way.

What is traffic enforcement?

The most common form of transportation policing can be found within traffic enforcement. And many of the people named above were killed during contacts with police officers that started either genuinely or in the guise of a traffic-related stop.

So why did our society task armed police with traffic enforcement in the first place? Sarah Seo, Associate Professor at the University of Iowa College of Law and author of Policing the Open Road, writes that in cities across the country police were called to respond to the quickly rising death, injury tolls, and congestion that came from the introduction and mass production of cars in the 1920s. Seattle was no different, calling for more police to help control traffic around the same time as our last great pandemic.

“One division which is rapidly growing both in volume of business and in importance is the Traffic Division,” writes G.G. Evans in “The Police Force of Seattle, Queen City of the Northwest” in the December 1919 National Police Journal (self-proclaimed as “America’s Greatest Police Magazine). “The enormous increase in the number of automobiles makes the relief of congestion an urgent problem and one requiring traffic attention.” The National Traffic Officers’ Association held its 1919 meeting at Seattle Police headquarters (they would pass a resolution supporting mandatory turn signals on cars).

In that same article, Evans writes that “the country had been infested by a notorious half-breed murderer” and then praises Seattle Police Chief Joel F. Warren for arresting 200 “lewd women” in a “house-cleaning” effort before soldiers from Camp Lewis came to the city for leisure. Just to give you an idea of the horrifically racist and sexist mindset back when Seattle Police was first dramatically expanding their traffic patrol efforts along with police departments across the nation.

During this time cities also justified the widening of roads and more paved roads as a way to solve congestion. Of course induced demand increased congestion only to reinforce the idea of further increasing police forces and further widening roads.

The wave of traffic from cars also brought about a tsunami of traffic laws. By criminalizing dangerous driving, nearly every person who drove became a potential criminal (the flow of traffic is very often well above the speed limit, for example). By then outlawing jaywalking, nearly every person who walked became a potential criminal, too. This all raised serious constitutional questions, especially related to the Fourth Amendment’s protections against “unreasonable searches and seizures.” For example, a traffic violation has become enough probable cause to stop people, question them, search their cars (or pockets) and run their names through police computers. At any point, something entirely unrelated to traffic can happen. Officers could mistakenly think (or claim to think) the person was reaching for a gun (Philando Castile), officers could not appreciate the tone of the person they stopped and get violent (Sandra Bland), officers could spot something in the backseat they claim is related to drug use, officers could discover that the person has a warrant out from some previous case or from unpaid tickets, etc. There are so many ways a simple traffic stop can turn into something much bigger, whether that’s immediate violence or getting trapped in the criminal justice system. (more…)