Seattle’s unofficial motto could easily be “The City of the Sharrow.” Keegan Hamilton at the Seattle Weekly once suggested the Seattle Sharrows as a name for a D-League basketball team.

And sure, why not? Take one glance at major streets in all corners of the city, and you’re bound to see two chevrons with a bicycle icon beneath it. The sharrow is the city’s most prolific graffiti tag.

There’s a reason I used the color-inverted sharrow as the logo for this blog (other than the free public use rights and a vague allusion to me writing with ink versus the city’s white road paint). In some ways, this simple icon tells the story of biking in Seattle perfectly: We’re a city that wants so badly to appear to be trying to make cycling safer and more accessible, but is so scared of actually making a significant change to roadway design that might upset anyone, that we have to-date painted well over 3,000 of these markings.

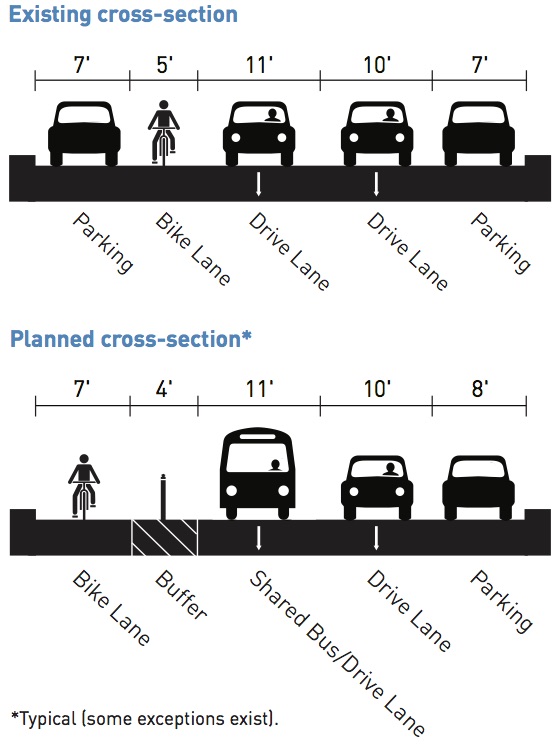

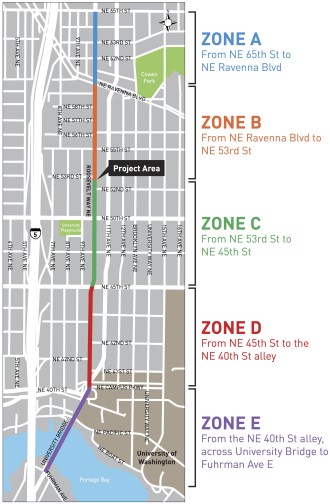

92 miles of the city’s claimed bicycle network consists of “shared lane markings.” These 92 miles are why you could be fooled looking at the official Seattle Bike Map into thinking the city’s bike network is fairly complete and connected. Of course when you actually get out on the streets, you encounter roads like NE 45th Street pictured above (and noted as a bike route on the bike map). Yeah, no.

Well, initial findings from a recent study out of CU Denver suggest that shared lane markings have had either no impact on biking rates and biking safety or may even have a negative impact. These results still need peer review, but they likely are not surprising to anyone who has found them of little help on major busy streets.

Seattle’s Josh Cohen has produced a great report for his most recent podcast at The Bicycle Story. Cohen not only spoke with one of the study’s authors, Wes Marshall, but he also tracked down James Mackay, a bike planner who invented the sharrow for the City of Denver in the 90s and helped get the marking into the national traffic design standards.

“Bikes almost became extinct in America, so it’s sort of like reintroducing them,” Mackay told Cohen. And the sharrow was invented for the reason you might expect: City leaders wanted to do something for biking without impacting general purpose or parking lanes. In a way, they were just to officially communicate that bikes do have a legal right to be on a street and should be expected there.

“The evolution of sharrows over the last two decades parallels the evolution of biking as transportation in America over the same period,” Cohen concludes, “they were [created] in an America that saw bikes as exercise equipment and children’s play things. (more…)